A series of the scale and scope of “Planet Earth: Blue Planet II” pushes into new cinematic territory, thanks to technological advancements allowing crew members to venture into places previously unexplored by humans. Producer Orla Doherty went to one such site, joining the first humans to dive 3,280 feet into the waters beneath Antarctica — the coldest on Earth — to explore enormous icebergs.

Even there in those frigid waters, life thrives in glowing, feathery tentacled variety. “Every dive that we did felt like we were going to another planet,” Doherty told Salon in a recent interview conducted during BBC America’s appearance at the Television Critics Association’s winter press tour. “You are getting into a capsule and it’s a little spaceship, except you’re just going down instead of up, and you’re landing on places that are just extraordinary and have probably never been seen before, and never will be seen again.

“Yes, these places are like other planets,” she added, “but it’s right here on planet Earth. This is part of our home.”

“Blue Planet II,” the latest jewel in the crown of the BBC’s nature documentary unit, makes its U.S. debut at 9 p.m. Saturday on BBC America, and will be simulcast on AMC, IFC, WE tv and SundanceTV.

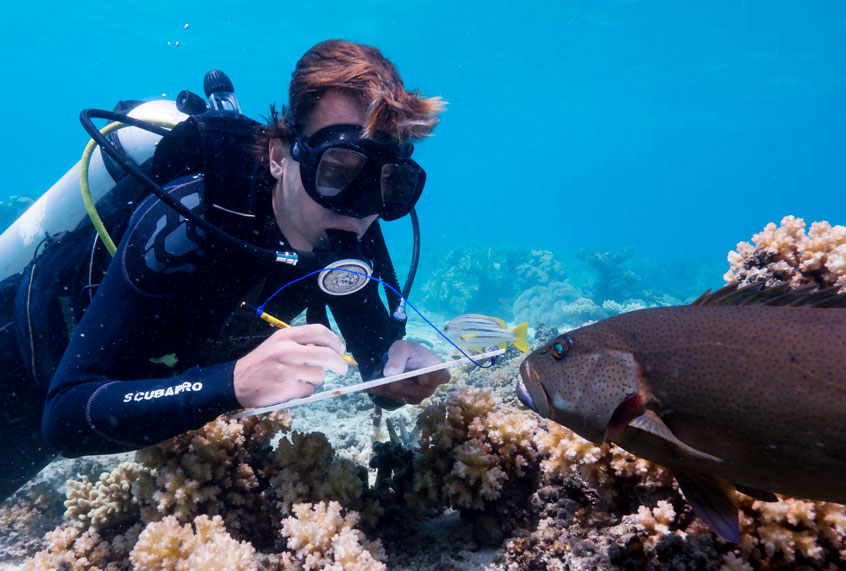

To make “Blue Planet II,” teams mounted 125 expeditions that touched every continent and every ocean, visiting 39 countries during production. They spent more than 6,000 hours diving underwater, reaching as far down as the Mariana Trench, the deepest part of the ocean.

Innovations in submersible vehicles and camera equipment allow the crew to venture to places the first “Blue Planet” could not in 2001, creating a series as full of wonder and discovery as it is with thrills and frights. In one of Doherty’s episodes, “The Deep,” some of life captured on film is alien to our understanding, naturally luminescent and entrancing. It is fang-filled as well, validating our concept of the sea as a place hiding terrors side by side with delights.

Executive producer James Honeyborne’s ambition with “Blue Planet II” is to increase our level of understanding and connection to our oceans. “This world might at first sight appear alien, remote, scary, dark, cold,” he said, “but it operates in many ways like the parts of the planet we’re more familiar with.”

Given the BBC’s reputation for setting new standards in nature documentary production, such as the worldwide popularity of “Planet Earth,” “Blue Planet II” doesn’t require much of a sales pitch. Few descriptors adequately capture what a visual delight these seven episodes are; at the very least, it may remind you of your high-definition television’s value and true worth.

Already the series has enthralled viewers in Britain, where it became the most-watched show of 2017 by attracting 14.1 million viewers to its opening installment, which aired on BBC One. According to Variety, those ratings made the U.K. telecast of “Blue Planet II” the nation’s most-watched natural history show in 15 years, and the third-most-watched show of any kind in the last five years, bested only by the 2014 World Cup Final and the “Great British Bake Off.”

The ocean requires little in the way of polishing in post-production, although time-lapse photography and slow-motion sequences add to our appreciation of this vast and varied ecosystem covering 70 percent of the globe. One scene displays the rolling arc of a wave, decelerated to resemble living crystal and moving silk. Then, breaking the powerful continuity of the surface, dolphins — leaping through the waves for, as the series narrator Sir David Attenborough tells, “the sheer joy of it.” This is how the series’ seven episodes are introduced in its first moments.

The marvels increase a thousandfold from there.

“Blue Planet II” grants close-up views of creatures ranging in size from the microscopic to the gigantic; the breath-halting entrance of humpback whales feasting on herring is particularly memorable. Filmmakers also captured images never before recorded on camera, such as the astonishing hang-time of a giant trevally as it hunts birds in flight. In a separate interview for Salon Talks, Honeyborne discusses the experience of watching these fish hunt birds as “astonishing behavior the likes of which we’ve never seen before.” See for yourself: the clip from the episode kicks in about four minutes and 54 seconds into the video.

Notably, the series spends ample time with creatures dividing their existences between land and water as well as those living beneath it, furthering the notion of connection between the audience and environs that appear unimaginably foreign.

Equally as entrancing as the views are the sounds and songs underneath the waves, magnified and clarified to an extent that adds another level of dialogue to Attenborough’s descriptions. Hans Zimmer’s score works in collaboration with these sounds, but just as often the vocalizations, clacking and thumps are left to speak for themselves.

As is true of “Planet Earth” and “Planet Earth II,” with “Blue Planet II,” the producers find the drama within acts of survival we assign to instinct. Organizing these moments creates a larger production, set on the world’s largest stage, that’s equal parts action film, ballet, romance and, yes, tragedy. In this production, fish are shown as having something resembling individual personalities, particularly one in the first episode, which is shown using a tool to get its dinner.

“Our job’s not to anthropomorphize,” Honeyborne stressed. “What you do get in this series, I think, is the sense of character coming through from those animals, because we’re able to spend a much longer with them. It was shocking to me that you could look a fish in the eye and realize it was so much more intelligent than we previously thought.“

At least one makes a reappearance in the “Blue Planet II” equivalent of a “Where are They Now” reunion episode. That revisit is shockingly sobering.

Rising sea temperatures and the changing chemistry of oceans make “Blue Planet II” more forthright and pointed as an environmental wake-up call than “Planet Earth.” The producers would probably call that unavoidable as opposed to intentional, since most of the evidence of human impact the crew encountered was unexpected.

In one instance, Doherty recalled diving in the depths off the Florida Keys seeking what was reported to be a surprising abundance of deep corals. “What we found was actually a trashed rubble field where a trawler had been through and decimated these very ancient corals,” she said. “We filmed it, of course, and it just felt important to include that. That even without consciously going down to destroy something, this practice of dredging the deep sea is really creating a very, very long-term impact.”

During the four years that the series was in production, “Blue Planet II” cameras witnessed the mass bleaching of shallow-water corals in the Great Barrier Reef, the largest die-off since records there began. A scientist guiding the “Blue Planet II” crew grew up exploring those corals and recalls crying into this mask the first time he saw the devastation.

But Honeyborne stressed that producers did not set out to look for these examples of impacts. “We set out to make a series about the wonderful and amazing sea creatures that there are beneath the waves,” he said. “There are real issues there that we see everywhere. That is just unavoidable. The bleaching coral reefs, yes, that was a very dramatic demonstration. . . . But equally, just the amount of plastic pollution, debris everywhere, it’s unavoidable. We see it. We encounter it. We encounter creatures trapped in it.”

Despite all the devastation the producers have seen while filming “Blue Planet II,” Honeyborne ardently believes there is still time to pull back form the brink, a message that pervades the seventh and final episode.

“The oceans have an incredible capacity to rebound, to heal themselves, if you just give them a chance,” he concluded. “That is a message of hope that comes through at the end.”