This January, Oxford Films released a documentary on Netflix entitled "Treasures of the WRECK of the Unbelievable." It appears to show, Discovery Channel-style, the exploration of a 1st century AD Roman shipwreck of colossal proportions: a vessel an estimated 60 meters long, which contained a legendary art collection, painstakingly assembled of the finest sculptures of the ancient world. It explains how Hirst financed this underwater archaeological excavation and how what was discovered filled Palazzo Grassi at the 2017 Venice Biennale, a show that got much press (but few good reviews).

Of course the whole thing is fictional, but it is fooling no one. Or rather, those that seek out and click to watch the documentary are almost all doing so because they know the story behind it. In order to create a playfully, overtly false provenance for his sculptures, Hirst and his team commissioned this documentary. The sculptures were all made by his studio over the course of ten years, at an estimated cost of $65 million. Along with scores of gold objects, the exhibit includes numerous sculptures made of bronze, including a colossus that filled the atrium of Palazzo Grassi and required the removal of the roof to install. Many of the sculptures are covered in “coral,” meant to appear as if they really had been dredged up from the bottom of the sea — and, oddly, not cleaned. The result was truly spectacular, as in it created a spectacle and was a marvel to look at, but critics were not impressed, deeming it a show “built for oligarch” shopping sprees. There was much tut-tutting about the suspicious coincidence of such a strikingly similar theme to Hirst’s show and that of respected but modest artist Jason deCaires Taylor, who has made a career of burying sculptures under the sea and allowing them to be covered by real coral. But while you may or may not be a fan of the works in Hirst’s exhibition, this “mockumentary” offering it a partially plausible backstory can be considered independent to it.

Mockumentary has become its own genre. The term refers to films or programs made intentionally in a documentary style for the sake of humor and commentary, sometimes appearing to be a sort of reality show, with handheld cameras (as in much of Christopher Guest’s work, like "Waiting for Guffman" or "Best in Show"), sometimes more formal and official-looking, as in this case. The prince of mockumentaries was the 1984 "This is Spinal Tap," one of the funniest movies ever made, following the ups and downs of a fictional British heavy metal band (Guest is a co-writer and played guitarist Nigel Tufnel). In terms of not-for-laughs mockumentaries, Orson Welles’ seminal film "F for Fake" was a postmodernist concoction about frauds, while also hiding a Welles-invented falsehood among the real stories of fraud on which it reported. Faux-documentary has also made its way into other genres, such as horror (consider "The Blair Witch Project" or "Paranormal Activity").

With all of these faux-documentaries, there is a willing suspension of disbelief akin to that which the public is asked to accept in feature films — we know that what we see is not real, made for entertainment, but we voluntarily allow ourselves to be immersed in the tension and emotion the entertainment produces, in order to be better entertained by it. Faux-documentaries make the suspension of disbelief easier, because it looks like what we’re used to seeing in “real” documentary programs. There may be advance publicity trying to reinforce the non-fiction-ness of the entertainment (the low-budget "Blair Witch Project" made a show of its content having truly been the found footage from a group of hikers who had disappeared), but at any point only a tiny percentage will be fooled. The rest of us, especially in the internet era, when spoilers and commentary are just a google away, know what we’re getting into. So why bother?

In the case of Hirst’s documentary, especially given my interest in the subject of fraud (one of my books is "The Art of Forgery"), I was in it to play “spot the fake.” You’ve done it before, I’m sure. Watch a magician at work, and you might applaud the sleight of hand, but a part of you is playing the game of trying to figure out how he did it. This was my interest in "Treasures from the WRECK of the Unbelievable." Would, I asked myself, this mockumentary fool me, if I did not already know the story behind it? Is it a successful attempt at the genre?

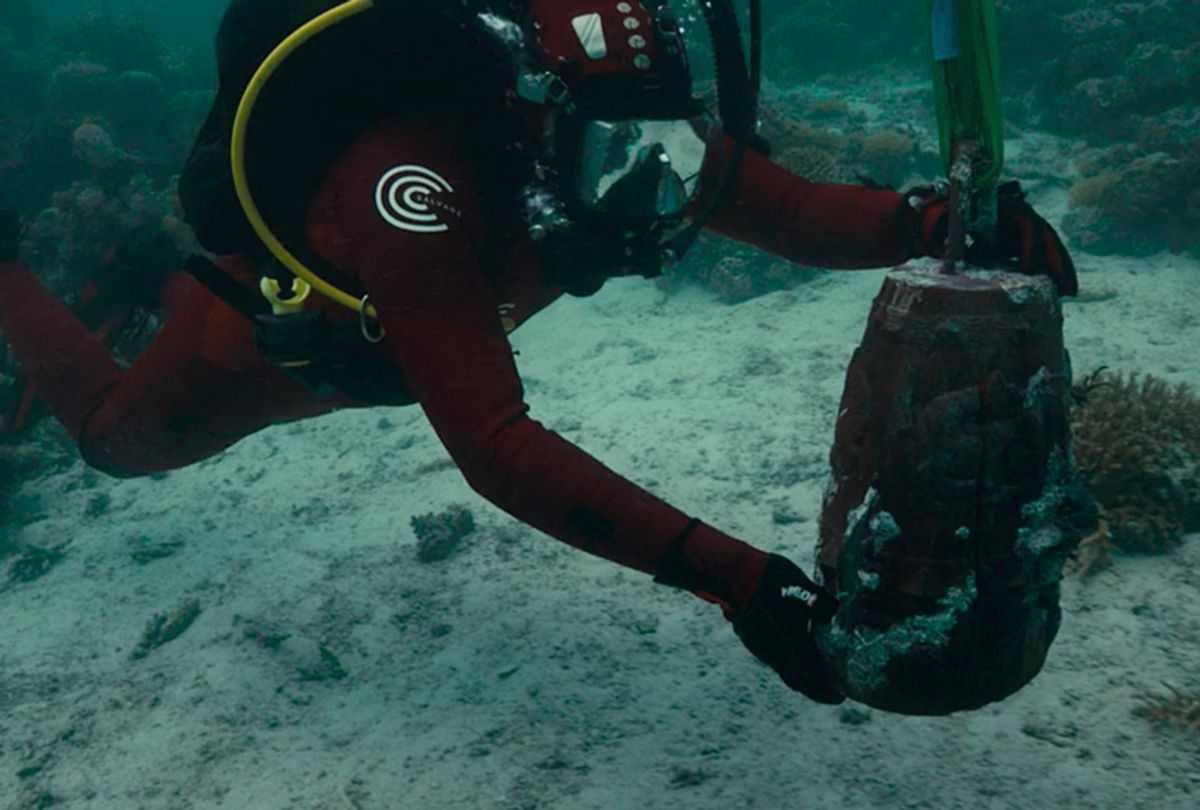

Stylistically, it certainly is. We meet various talking heads, see tensions between members of the expedition team, learn backstory of the legend of the lost treasure ship, and see divers (in very nice underwater sequences) as they find various statues and haul them to the surface. Let it be said that the filmmakers are not in the least malicious — they are not trying to make a film that would mislead, and the timing of its release, six months after the exhibition, and all its spoiler coverage, was announced, means that only a handful of accidental viewers won’t know the story behind it ahead of time. As a result, there are some clues laced throughout that the vigilant viewer can use to reveal the truth of the falsehood. Some of the talking heads, for instance, are labeled as hailing from non-existent institutes of research and higher education. A pan past a so-called archaic classic sculptural torso found at the wreck has the word “CHINA” (as in, “Made in”) written on its back. One of the statues is clearly a self-portrait of Hirst. Then there’s the fact that archaeologists would never leave the coral on statues when putting them on display.

But the real giveaway is the art itself. It is certainly impressive, but it is far too hyper-realist to actually be from the ancient world. It was made via 3D printing, and it shows. It looks hopelessly modern. That’s okay, some people like that, but no one with any knowledge of ancient statuary would be fooled. The best piece of the group, the colossus in the central courtyard of Palazzo Grassi, so large that grown humans come up to its ankles (and a legit modernization of the colossi of the ancient world, like the Nero statue that once stood where the Colosseum is today, or the Colossus of Rhodes), is the most believable, but the majority of the pieces, while sparking awe and wonder in the viewer, would never pass muster as possibly ancient. And so the mockumentary’s main giveaway is the art itself. I’d far rather have seen the whole affair be taken further, deeper, with actual ancient-style statuary made with ancient methods. But impatience, or possibly lack of talent on the part of the sculpture-makers (for to call them sculptors in a traditional sense would be misleading), led to a very expensive, shorthand methodology of 3D printing that, while produces wows, also shines with inauthenticity.

Shares