The truth about a writer being anointed a Voice of the Generation is that it’s also a curse. On one hand, it means this young talent captures with singular insight the burgeoning zeitgeist in a way that the elder generation of literary gatekeepers no longer can. On the flip side, it also means an immediate casting of odds on whether the precocity can hold up under the extra critical scrutiny, the pressures of a public life and the follow-up demands in a merciless world that — especially in the case of young women — is half-expecting them to self-destruct first.

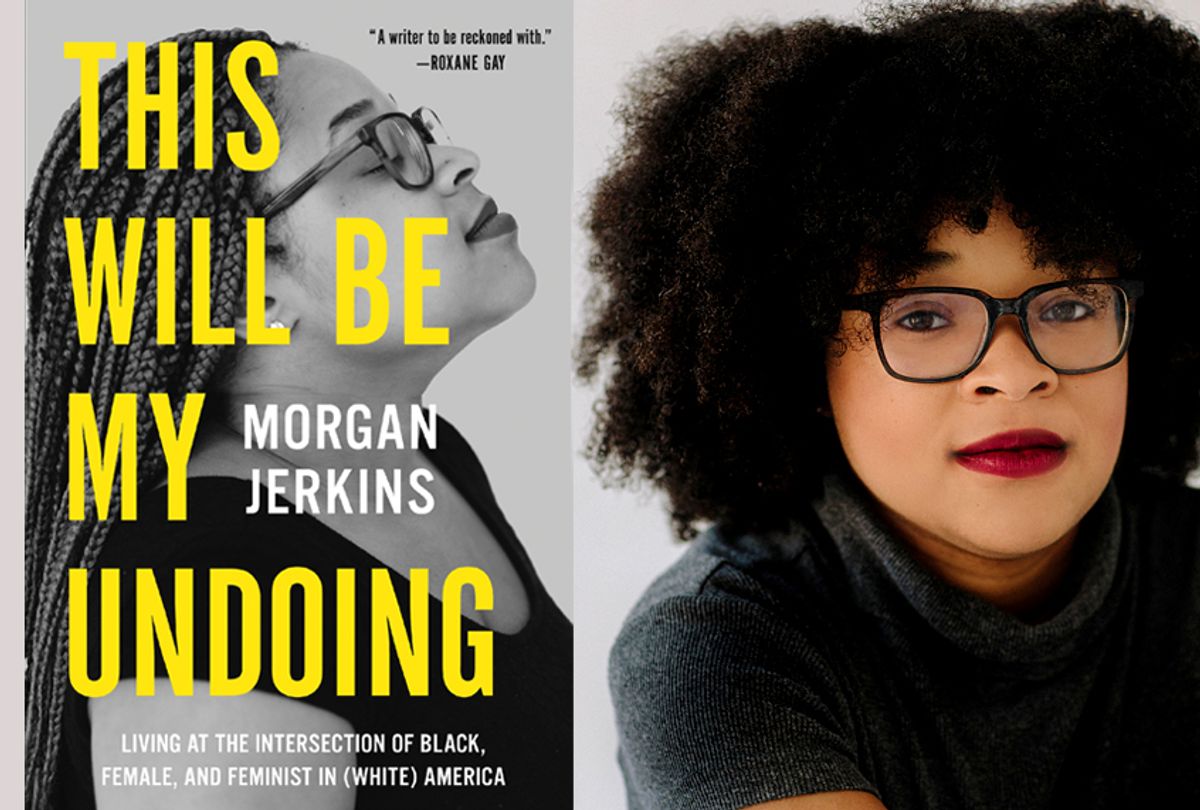

Who needs that extra pressure? But humans like to classify, to rank, and one way that need manifests itself in the books world is to elevate an author out of the already-elite pool of emerging writers of promise to next-level glory and attention. Guilty, I guess: I hope it’s not too forward of me to nominate the 20-something New York-based writer Morgan Jerkins, whose exhilarating new essay collection “This Will Be My Undoing” makes her a leading contender for the title — and the writer most likely to rewrite the rules for it, too.

The label has long been applied mostly to breakout novels — though by the ‘90s, memoirs like Elizabeth Wurtzel’s “Prozac Nation” (1994) and Dave Eggers’ “A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius” (2000) were also name-checked — by white male writers like F. Scott Fitzgerald, Joseph Heller, Jack Kerouac, Douglas Coupland and Bret Easton Ellis, who had captured, as TIME critic Lev Grossman wrote in 2006, a certain something of the times, which he describes as “the yearning and the rage of the contemporary, embodied in some poor sad sack of a character who's mad as hell and just can't get no satisfaction.”

"I think youth has a lot to do with it," Ellis, himself such an anointed Voice, told Grossman. "Being the first — and not necessarily the best, just the first — to capture what it feels like to be a member of your generation catapults you forward . . .”

One thing social media has done in the decade-plus since Grossman's story, let alone in the years since Ellis hit the scene, is demolish the expectation that anyone can be “first” in this particular way. And the thriving genre of young-adult fiction is brimming with excellence, so the sweet relief of finding a fictional protagonist who gives voice to a heretofore-unarticulated new tone and mood in the culture isn’t quite so rare anymore. It makes sense, then, in a digitally connected world where everyone who wants a platform has one, that the essay — where a writer’s voice is unmistakably her own — would be where we find it now.

If you can no longer be the first — especially given the ubiquity of the 20-something-year-old essay writer, primarily in online spaces — you can be among the best. Excellence and clarity of vision are what put Jerkins’ essays ahead. In an attention economy often dominated by the messy exhibitionist, Jerkins instead employs scalpel-like precision to her ten essays on, as the book’s subtitle states, life at the intersection of being black, female and feminist in (white) America. These essays cover an ambitious amount of ground, including but not limited to body image, gentrification, mental health, class, race and racism, misogynoir, religion and faith, Russia and Japan, Beyoncé and Michelle Obama, sexuality, joy, anger, grief and sensuality. Her poet’s eye for the unexpected, perfect connection pushes her intellectually rigorous and expansive blend of memoir and cultural criticism to surprising places.

One of the central themes uniting Jerkins’ collection is the emphatic assertion — which is still maddeningly necessary — of black women’s essential humanity. The heart of the book is a riveting 44-page essay titled “Black Girl Magic,” which explores what it means, and what it can take, for a black woman in America to heal — psychologically, emotionally, physically — rather than continue to bear pain. These connections flow freely but with a sense of purpose and momentum, and the essay never spins out of control.

The essay begins with anxiety, which crept into her life as her stepfather’s health deteriorated during her sophomore year at Princeton. Despite his career as a psychologist, she writes, “Black people do not do therapy. . . . We go to God with our problems. Therapy is for white people with money. It is a pastime, a hobby, a luxury.” From there, she turns to how the medical field has throughout our history exploited black people through unethical, immoral experiments and unequal treatment and how that torture has contributed to the imagining of the Strong Black Woman, which “dehumanizes us by not acknowledging our human weakness and needs.” This she connects to the concept of “Black Girl Magic,” an idea and an ideal celebrating the positivity and genius of black women and girls, and she critiques her own evolving understanding of how ableism has left some black women and girls out. This leads her to physical pain, which she connects to her own labiaplasty, the personal history of and experience which she renders with both delicate vulnerability and defiance.

Words often associated with women’s writing, especially concerning their pain: unflinching, fierce, brave. But these terms of praise are often code for the literary equivalent of battlefield surgery crossed with bedroom voyeurism. Later, that willingness to scar on the page for the thrill of the reader, once valued, can be used against them. This demand has to be even more treacherous territory for black women, who are also, as Jerkins explores deeply in her work, writing within an economic system that has a long and disgraceful history of dehumanizing black women and their bodies. (Witness the Los Angeles publishing party Jerkins describes in the essay, where she conducts herself with self-conscious decorum amidst “the kinds of behaviors that I only saw in decadent HBO series, or read about in personal essays written by white women,” despite wanting “to f**k up . . . to see what it was like to be so carefree, so white.”) That Jerkins decides to write about such an intimate part of her personal history as a labiaplasty with as much self-compassion as she does — not pity, compassion — is downright revolutionary, and can provide a model for writers of any age.

If being called a Voice of the Generation is a curse, it is a curse that Jerkins is well-positioned to conquer by doing the work of constantly pushing herself to top her last effort, not through sheer luck of the zeitgeist. If this collection is any indication, her blueprint for a lifelong intellectual and creative enterprise will continue to challenge, thrill, and delight her readers throughout a long career. In the essay “Who Will Write Us?,” which examines Beyoncé’s “Lemonade,” the French film “Girlhood” and the picture book “A Birthday Cake for George Washington” in an exploration of why black women need to tell black women's stories, Jerkins writes:

I want to know, I want to know, I want to know. I want to know, but not just to know. I want to realize that anger metamorphosing into power, that power channeling into humor, that humor gliding past white consciousness, and that white consciousness never being able to fathom what that humor entails. My idea of a black narrative is one that subverts, flips, and undermines rule until that final product cannot be duplicated by anyone other than one with black hands.

She closes the essay with a thought about voicing the experience of black women in America: “there isn’t just one; there are many. Millions, to be exact. I can add only one.” That simultaneous fidelity to giving voice to her own specific experiences and insistence on spaces for other black women to do the same encapsulates one of the most urgent and admirable qualities of this generation of young adults. But Morgan Jerkins doesn't need me, a 40-something-year-old white critic, to tell her or the world who she is or who she speaks for. Her book, and those to come, are more than up to that job.

Shares