As the federal government heads toward another government shutdown deadline on Thursday, neither party seems to have a clear idea how it wants to deal with the situation or how to resolve the immigration issue that precipitated the last shutdown.

In January, Democrats had vowed to shut down the government unless President Donald Trump and congressional Republicans agreed to extend legal protections to the people currently registered under the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program. Trump has announced an end to the program, which was never authorized by Congress.

Once the lights were out, however, it soon became evident that while the public seems to be closer to the Democratic position on immigration, independent voters largely did not want Democrats to shut the government down in order to force a DACA deal. Chastened by several polls that broke against them, 32 Senate Democrats joined with the vast majority of Republicans in the chamber and voted for a short-term package that would reauthorize funding until Feb. 8.

The last shutdown illustrated several key dynamics of the American political system that periodically seem to be forgotten. The first is that majorities don’t necessarily matter. Trump is the president, despite losing the popular vote to Hillary Clinton by a 2 percent margin, which clearly demonstrated that a majority vote doesn’t always drive victory in the Electoral College.

Majorities also do not necessarily matter in Congress, either. Thanks to Republicans’ disproportionate strength in sparsely populated states, they ended up with 52 Senate seats after the 2016 elections, even though their candidates got 10 million fewer votes across the country. Democrats won 53.5 percent of the vote in senatorial elections, while Republicans received 42.4 percent. (Democrats had a net gain of two Senate seats in that election but had hoped to win many more.)

(That dynamic did not hold true in the national vote for the U.S. House of Representatives, which Republicans narrowly won, 49.1 percent to 48 percent.)

In terms of policy, the idea that the majority rules is not true either. On the topic of gun rights, decades of polling have shown that the public supports at least modest restrictions on firearm ownership. But even when Democrats controlled both houses of Congress and the presidency during Barack Obama’s first term, there was no real progress on that issue.

The same thing happens with regard to tax policy. The American public broadly supports higher taxes on wealthy people and more taxes on business. The tax plan that Republicans passed and Trump signed into law in December does the exact opposite.

There are numerous other issues I could cite to demonstrate that what most Americans want is not necessarily what Congress is likely to do. The interesting question, however, is why that’s true.

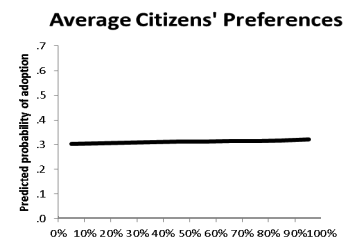

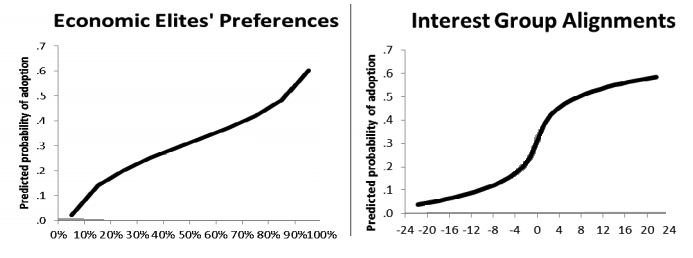

Money certainly has something to do with it. A 2014 study by Martin Gilens of Princeton and Benjamin Page of Northwestern found that the preferences of high-income people were excellent predictors of whether a policy became law. Their research showed almost a perfect correlation between the percentage of wealthy people supporting a policy and its actual passage. By contrast, the opinions of average-income people about a given issue seemed to have essentially no impact at all.

The research also showed another factor at work besides income, however, and that was passion about the issue. When a hot-button political opinion was important enough to lead an interest group to begin supporting it, that strengthened the issue’s chances of becoming law.

What this means is that on many issues, the people who are most passionate about them will determine the policy, even if their numbers are relatively small. That’s certainly the case with regard to gun control, where even a majority of Republicans has supported the idea of requiring firearms purchasers to obtain a police permit since 2006. That hasn’t mattered, because Republican elected officials are much more inclined to listen to the views of the small organized minority who disagree and have banded together in support of organizations like the National Rifle Association and the Gun Owners of America. Even some Democrats, like former Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid have been eager to keep on the good side of gun-rights supporters.

A similar dynamic appears to be at work on the topic of immigration. While a large majority of the public supports legalization and citizenship for DACA recipients, the people who care most about immigration appear to be those who want the most severe clampdown.

In a Gallup poll in January, 16 percent of respondents who identified or leaned toward the Republican Party said that immigration was the most important political problem facing America today. The question was an open-ended one, which meant that people being polled could literally say anything. The 16 percent number actually made immigration the most important issue among Republicans, tied with general dissatisfaction with government and the federal deficit, health care, terrorism and racial matters.

When people who lean toward or identify as Democrats were asked the same question, just 4 percent said that immigration was the most important issue to them. Seven other issues ranked higher among Democratic voters.

The Gallup survey is no outlier either. In a poll done last February by CBS News, immigration ranked as the top issue among Republicans, with 25 percent saying it was the topic they wanted government to address most. Just 8 percent of Democrats said the same. The much larger national exit poll conducted in conjunction with the 2016 presidential election found that among people who ranked immigration as their most important issue, Trump won the votes of 64 percent. His opponent Hillary Clinton won just 32 percent.

All of this has put congressional Democrats in a real bind. Their most loyal base voters clearly want them to stand up to Trump and drive a hard bargain on immigration. But political reality, especially during an election year when Democrats have a realistic chance of recapturing a House majority, seems to suggest they might be harmed by playing too tough.

Even some of the most determined advocates for DACA legalization now seem to be realizing this. During the January shutdown, Rep. Luis Gutiérrez, D-Ill., told CNN that he would be in favor of authorizing Trump’s much-ballyhooed border wall program if it meant making a DACA deal.

“I think it would be a monumental waste of taxpayer money to build a monument to stupidity, but if that is what it is going to take to get 800,000 young men and women and give them a chance to live freely and openly in America, then I’ll roll up my sleeves, I’ll go down there with bricks and mortar and begin the wall,” he said.

Notably, every single Senate Democrat who appears to be considering a presidential campaign in 2020 seemed to disagree with that position. The Democratic vote to reopen the government was also strongly condemned by groups on the progressive left.

Paradoxically, while reaching some sort of immigration deal with Trump might anger some leftist groups and dedicated Democratic activists, it would almost certainly harm the president more.

There are three reasons for this:

- Republican voters are far more opposed to the idea of political compromise than Democratic voters are. When Republican politicians make compromises, that tends to anger and demoralize their voters to a much greater degree.

- On the topic of immigration, Trump’s most devout supporters have repeatedly urged him not to sign on to a deal granting citizenship to DACA recipients. Everyone from Ann Coulter to Breitbart News and the white nationalists on the “alt-right” has warned Trump not to cut an immigration deal with Democrats. If Democrats can get half their loaf today while discouraging Trump’s base — the hardcore supporters who got him the 2016 GOP nomination and who don’t want him to do anything on immigration — that might set them up for a sweeping victory in the fall elections.

- Giving Trump some policy changes and funding for the border wall, in exchange for citizenship for 1.8 million undocumented immigrants, is essentially trading a set of policies that can be reversed by future Democratic administrations for a citizenship grant that cannot be reversed by anyone. Even if Trump gets everything he wants on his immigration “framework,” he would still disappoint his core constituency on its most important issue.