The fruits of modernity are self-evident, and modern men and women experience these fruits in their everyday lives — when they go to the pharmacy to pick up antibiotics, when they fly halfway around the world on a jet aircraft, when they turn up the heat in their home during the winter and so on. Admittedly, these material gains are so ubiquitous today that many people have difficulty imagining a time when they did not exist — but few can deny with a straight face that they are real, or that human beings on a whole live a better life today than ever before.

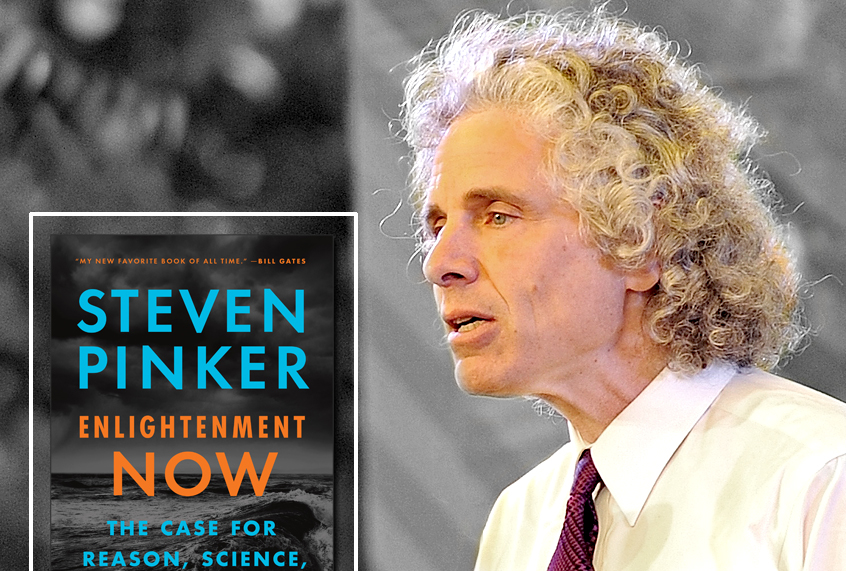

According to Harvard psychologist and linguist Steven Pinker, however, this may not be the case. In his new book, “Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress,” which has received rave reviews from many commentators, Pinker suggests to readers that progress is under attack on all fronts — a claim that may not sound unreasonable considering the far-right movements that have been gaining momentum across the globe in recent years.

Yet in Pinker’s account, what he calls “progressophobia” is not just prevalent on the right, where reactionaries long for the “good old days” and reject modernity out of hand, but on the left, where pessimistic progressives constantly deny or ignore much of the progress of the 20th century. Indeed, throughout his book Pinker seems more concerned with obscure left-wing “progressophobes” in academia than with right-wing reactionaries in the corridors of power. “Intellectuals hate progress,” declares Pinker at the top of his chapter on progressophobia. “Intellectuals who call themselves ‘progressive’ really hate progress.” (A lifelong academic himself, Pinker clearly has a bone to pick with his more left-leaning colleagues.)

The Manichaean narrative presented by Pinker throughout his book pits descendants of the Enlightenment (like himself) against the progressophobes of the counter-Enlightenment, with the former representing everything that Pinker loves — science, reason, progress — and the latter embodying everything he loathes. Not surprisingly, then, all the progress that Pinker documents in his overlong polemic is attributed to the ideas and values of the former, while all of the horrors of the modern world are blamed on the latter.

As an intellectual history, “Enlightenment Now” is an embarrassing failure that makes one question whether Pinker has seriously read the original texts of the Enlightenment thinkers he extols (or the “counter-Enlightenment” thinkers he assails, such as Nietzsche). “One of the features of the comic-book history of the Enlightenment he presents is that it is innocent of all evil,” observes philosopher John Gray in his New Statesman review of the book. “The message of Pinker’s book is that the Enlightenment produced all of the progress of the modern era and none of its crimes. … With its primitive scientism and manga-style history of ideas, the book is a parody of Enlightenment thinking at its crudest.” Similarly, in an excoriating review for the Australian public broadcaster ABC (not the American network), historian Peter Harrison accurately sums up the book’s strategy as follows:

Take a highly selective, historically contentious and anachronistic view of the Enlightenment. Don’t be too scrupulous in surveying the range of positions held by Enlightenment thinkers — just attribute your own views to them all. Find a great many things that happened after the Enlightenment that you really like. Illustrate these with graphs. Repeat. Attribute all these good things [to] your version of the Enlightenment. Conclude that we should emulate this Enlightenment if we want the trend lines to keep heading in the right direction. If challenged at any point, do not mount a counter-argument that appeals to actual history, but choose one of the following labels for your critic: religious reactionary, delusional romantic, relativist, postmodernist, paid up member of the Foucault fan club.

Rather than offering a fair and accurate portrayal of the Enlightenment and the thinkers (and critics) it produced, the vast majority of “Enlightenment Now” is devoted to “expounding the obvious,” as Jennifer Szalai put it in her critical review for the New York Times. Of course, Pinker would likely respond to this by stating that the progress he documents in his book is not so obvious to most, and that many people today — namely, progressophobes — are ungrateful for what we have and need to be reminded. “Life before the Enlightenment,” he writes toward the end of his book, “was darkened by starvation, plagues, superstitions, maternal and infant mortality, marauding knight-warlords, sadistic torture-executions, slavery, witch hunts, and genocidal crusades, conquests, and wars and religion.” If this is not expounding the obvious, then the sky is not blue.

Ultimately, Pinker’s real problem with progressives and left-wing critics seems to be that they acknowledge not only the good that has come from modernity, but also the bad and the ugly. Consider Pinker’s brief treatment of the late sociologist Zygmunt Bauman, who famously examined how the Holocaust was deeply connected to modernity. Without looking at his argument in depth, Pinker asserts that Bauman’s “twisted narrative” lets Nazis and their “counter-Enlightenment ideology” off the hook for the Holocaust. Either the Harvard professor has never actually read Bauman’s work, or he is purposely misrepresenting the Polish (and Jewish) thinker, who fought against the Nazis for the First Polish Army during World War II. In “Modernity and the Holocaust,” Bauman convincingly makes the case that the Nazis’ greatest crimes would never have been possible in a premodern setting:

At no point of its long and tortuous execution did the Holocaust come in conflict with the principles of rationality. The “Final Solution” did not clash at any stage with the rational pursuit of efficient, optimal goal-implementation. On the contrary, it arose out of a genuinely rational concern, and it was generated by bureaucracy true to its form and purpose. … [The Holocaust] was clearly unthinkable without such bureaucracy. The Holocaust was not an irrational outflow of the non-yet-fully-eradicated residues of pre-modern barbarity. It was a legitimate resident in the house of modernity; indeed, one who would not be at home in any other house.

How this lets the Nazis or their ideology “off the hook” is a mystery. But Pinker is uninterested in examining the central role that instrumental rationality played in the Holocaust and 20th-century totalitarian movements, nor is he willing to seriously engage with critiques of modernity.

In the end, “Enlightenment Now” is an erudite defense of the status quo and an apology for global capitalism (not surprisingly, the second-wealthiest man in the world as of this writing, Bill Gates, has named Pinker’s new book his “new favorite book of all time”). Though Pinker calls himself a classical liberal, by today’s standards it would be more accurate to call him a conservative (by comparison, the modern Republican Party, though labeling itself as conservative, is politically reactionary). Predictably, Pinker berates the left for “its contempt for the market and its romance with Marxism,” while insisting that industrial capitalism “launched the Great Escape from universal poverty in the 19th century and is rescuing the rest of humankind in a Great Convergence in the 21st.”

The irony here is that the great bogeyman himself, Karl Marx, would have largely agreed with Pinker’s contention about the progressive tendencies of capitalism. He called capital a “great civilizing influence,” and in the “Communist Manifesto” praised the “bourgeoisie” for creating “more massive and more colossal productive forces than have all preceding generations together.” Marx was an heir to Enlightenment thinking, and thus believed in the “project of modernity,” as German sociologist Jürgen Habermas has called it. But Marx also recognized the destructive and exploitative nature of capitalism, and like democratic socialists today who have rediscovered his work, Marx believed that the values and ideals of the Enlightenment could only be fulfilled by transcending capitalism and ushering in a socialist future. Pinker, on the other hand, ignores or rejects critiques of modernity (and capitalism), and is highly satisfied with the status quo, recommending only minor tweaks to counter certain undeniable problems, such as climate change.

Pinker presents his book as a case for optimism, but ultimately it is a case for quietism. After all, if “everything is amazing,” and if the status quo has indeed produced all of the great progress of modernity and none of its ills (which, according to Pinker, are either nonexistent or greatly exaggerated), then surely the status quo is not something to be overcome, but preserved and nourished. It is no wonder that he has received such high praise from establishment critics like David Brooks and neoliberal icons like Gates, who perceive the populist and anti-establishment uprisings of recent years as an irrational backlash against progress.

Though Pinker rails against “prophets of doom” on the left, progressives are the true optimists. Consider Pinker’s fellow linguist and former MIT colleague Noam Chomsky, whom the former no doubt regards as a pessimistic progressophobe. While Chomsky is widely recognized for his somber political critiques, he is not a pessimist but a realist who understands that much of the progress that has been achieved over the past century resulted from constant struggle against an unjust status quo. “Optimism is a strategy for making a better future,” Chomsky has said. “Because unless you believe that the future can be better, it’s unlikely you will step up and take responsibility for making it so.”

Another thinker Pinker briefly mentions is “Frankfurt school” critical theorist Max Horkheimer, whom the Harvard professor regards as yet another counter-Enlightenment, “quasi-Marxist” progressophobe. It is undeniably true that Horkheimer and other critical theorists were highly critical of modernity, but that hardly means he was opposed to progress or the enormous material gains that had been made in the modern world. “I believe that Europe and America are probably the best civilizations that history has produced up to now as far as prosperity and justice are concerned,” said Horkheimer. “The key point now is to ensure the preservation of these gains. That can be achieved only if we remain ruthlessly critical of this civilization.”

Being ruthlessly critical of the modern world does not make one anti-modern, just as being critical of American foreign policy does not make one anti-American. Modernity is a mixed and often contradictory affair, and acknowledging that does not make one a pessimist, a postmodernist or a “progressophobe.” In fact, it is necessary for any true progressive.