The true tale of Donald Trump's journey from reality TV show character, professional wrestler wannabe, serial adulterer and supposed billionaire to president of the United States is stranger than fiction. This is a living nightmare for Trump's opponents and others terrified by the harm he is doing to American society -- and a dreamlike state of political ecstasy for Trump's supporters.

In many ways, this discord and chaos are by design. Donald Trump's voters, along with the right-wing think tanks, plutocratic monied interests, conservative media and Christian fundamentalists have long wanted to break America's political and social norms, punish those they view as not "real" Americans", gut the social safety net, destroy the commons, and ultimately the undermine the very idea of democratic government. Trump is a means to an end; he is a human political bomb.

How does one assess the health of a democracy? Is the poison that Donald Trump and the Republican Party have injected into the American body politic lethal? Is American democracy truly exceptional? Can a multi-ethnic and multiracial democracy such as the United States survive the white nationalist and white supremacist identity politics of Donald Trump and the Republican Party?

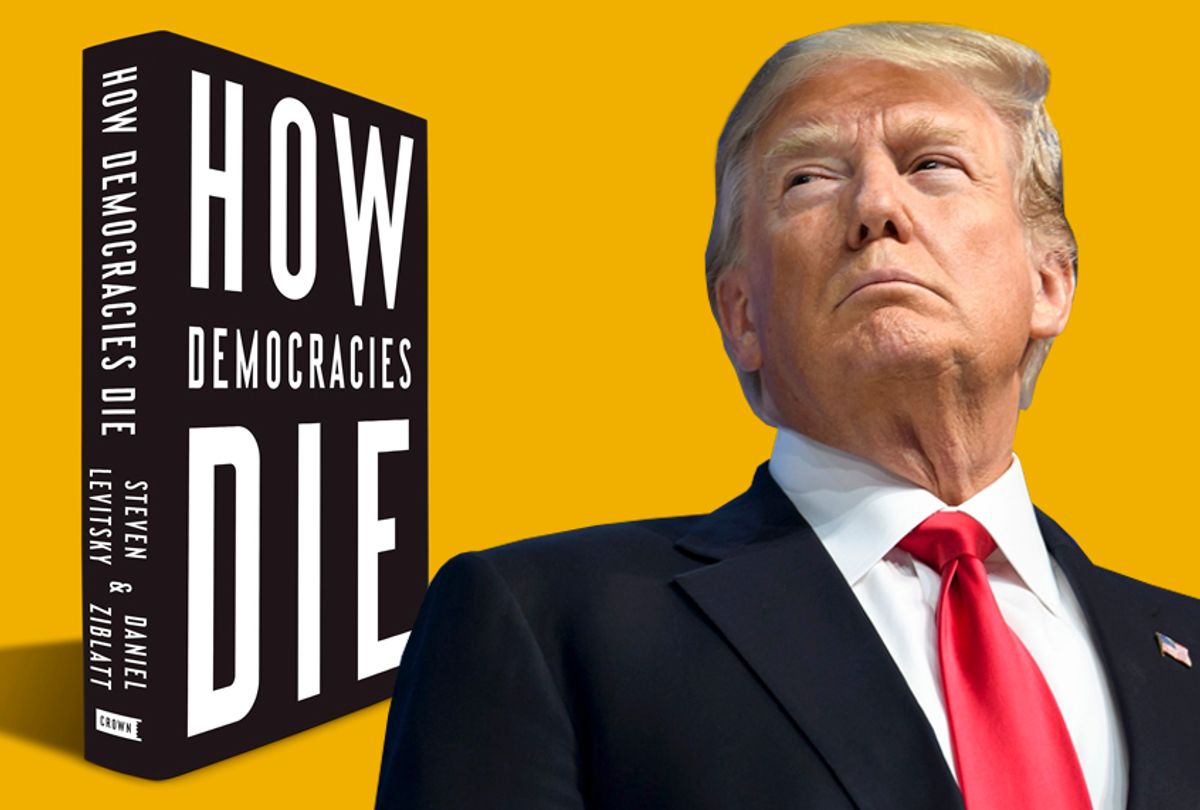

In an effort to answer these questions I spoke with Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt. They are both professors of government at Harvard University and the co-authors of the widely discussed new book "How Democracies Die."

This conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

How would you explain the election of Donald Trump?

Daniel Ziblatt: I think there is mass disaffection with our political system. What was different this time was that one of the country's main political parties, the Republican Party, failed to serve its gatekeeping function to keep a demagogic figure out of office. The most important question to explain is not why Donald Trump beat Hillary Clinton, but why Donald Trump got the [Republican] nomination in the first place.

Steven Levitsky: The United States has had no shortage of authoritarian demagogues circling around our polity and many of them, whether it's Henry Ford in the early '20s, Huey Long in the 1930s, or George Wallace in the '60s had a fair amount of public support -- in terms of percentages not far from Donald Trump. What is new is that a major party nominated him and then after nominating him basically lined up behind him.

Has American political culture just become so extreme, with a radicalized right wing, that a demagogue president like Donald Trump was inevitable?

Ziblatt: There's always a kind of sub-current of authoritarianism in American political culture, and there's always a segment of the population that support these types of figures. What really changed are two things. One, the way we select our presidential candidates changed. Beginning with the increasing importance of primaries after 1972 it actually became easier for a figure like Trump to get through. The second big thing is simply that everybody kept waiting for the party establishment to step in and we discovered that the Republicans have a very hollow organizational core. There were no party leaders to step in and say, "We'll endorse somebody from the other side."

Levitsky: I would also add that in many respects, Fox News and a handful of AM radio personalities exert greater leverage over candidates and candidate selection than the Republican Party establishment itself.

How would you evaluate the role of the news media as "guardians of democracy" in the era of Trump?

Levitsky: In a sense, there is no single fourth estate anymore. There is now a very fragmented, very diversified, and very partisan media. This is not the first time in history and certainly not the first country in the world where the news media has been partisan. In fact, in most places at most times in history, the news media has been quite partisan, but there's no question that it is reinforcing our polarization.

I actually think that the establishment media -- what is often referred to as the "mainstream media" -- are doing a pretty good job of highlighting the abuses of power and the norm violations carried out by this government under Trump.

What are some of the metrics commonly used to assess the health of a democracy?

Levitsky: We look in comparative politics for regular free and fair elections; not just elections but elections in which people can exercise the right to vote freely and fairly, in which the conditions of competition are reasonably fair. Second, a broad protection of civil liberties: the right to organize, the right to protest or to free speech, freedom of the press, and whether an elected government has the power to govern, making sure that there's not a power behind the throne, be it monarchs or militaries or ayatollahs who limit the power of elected officials. It's relatively easy to determine the existence of a democracy.

The health of a democracy is a lot harder because there are many, many dimensions that you can evaluate -- public opinion, the state of the economy, how well institutions are functioning -- you can go down the line. I think it's a much harder, more elaborate task. The United States is still fully democratic. The health of democracy is a much more difficult problem to evaluate.

Donald Trump is the symptom, not the disease. Do you think that observation is correct?

Ziblatt: It's clear that the election of Trump has focused our attention on this acute moment but there are deep underlying problems that gave rise to his election. For example, there are deep underlying processes of political polarization. The norm erosion that we highlight in "How Democracies Die" is being driven primarily by the radicalization of the Republican Party, which has become the representative of a declining white majority and its electoral power.

How did a decline in civic literacy make Trump's election possible?

Ziblatt: People have the sense that public community is disintegrating. It is certainly exacerbated by a transformation in the country's media landscapes and investments in education. A lot of these things are driven by public policies where if we can't even agree on the basic rules of the game, it's going to be even more difficult to formulate public policies and come up with solutions for the kinds of problems that are necessary to sustain a democracy.

Levitsky: Yes, civic literacy helps, but ultimately, we place a lot of responsibility on political leaders and political parties. Here I think the Republicans, in particular, have failed us. At times politicians have to lead, they have to say to their base, "No, we're not going to do what you want. We're going to do what's good for the country, we're going to defend institutions." That sort of leadership has been completely absent for the last 10 or 15 years in particular.

How do we locate American exceptionalism relative to the global rise of anti-democratic and illiberal politics in this moment?

Levitsky: First of all, I'm not sure that there is a global wave against democracy. The evidence is not so overwhelming. There are some trends that are worrisome. For example, I am very concerned about how Western democracies are responding to immigration and ethnic diversity.

The idea of American exceptionalism is existentially problematic because it has led too many people to take American democracy for granted. There is an assumption that no matter how recklessly our politicians or our parties may behave, we can't possibly break our democracy. This is a really dangerous way of thinking. If the American people continue to shut our eyes to history and to the rest of the world and simply act on faith that we are somehow immune to all this, we'll realize the extent of the crisis far too late.

Ziblatt: Looking to other countries we can also see some things that are different about the United States. It is a much older democracy as compared to those countries whose democratic order has broken down. The United States also has the oldest written constitution in the world, a much more robust civil society than some of these other countries, and a much stronger economy. The United States is distinctive in that way.

There have been surveys and interviews in which Trump supporters said they did not care if Vladimir Putin interfered in the election because "their guy" won. This is evidence of wanting to win at all costs, with no respect for democratic norms and institutions.

Levitsky: This is a sign of the type of extreme polarization that has wrecked democracies elsewhere. Gallup polls throughout 2017 showed that Putin has a much higher approval rating among Republicans than Hillary Clinton. Think about that. That's pretty stunning.

There's also another data point that I like to point to: The exit poll on election night 2016 found that about one in four of Trump voters said they believed he was not fit for the office of the presidency. Yet they still preferred Trump to the Democrat. That is a sign of extreme polarization and it reminds me of Latin America in the 1960s and '70s.

Ziblatt: To sustain a democracy, norms of mutual toleration are critical, as is the willingness to treat your rivals not as enemies but rather as fellow loyal citizens.

What are the "pressure points" in a democracy that demagogues and authoritarians try to leverage?

Ziblatt: There is a common set of strategies that authoritarians use. They go after the referees of the political systems: law enforcement, courts, judges. They go after their rivals as well as the media and the opposition. They try to sideline these groups and then they try to institutionalize the advantages they have made by tilting the playing field through changing the rules in the political system to lock themselves into power.

Ultimately, once an autocrat is in power who wants to dismantle democracy -- or even just wants to protect their own interests -- they will find those points of the political system to try to manipulate in order to defend themselves and go after their opponents.

How does the color line intersect with this political moment, specifically, and political polarization more generally?

Ziblatt: For most of our history, race didn't enter centrally into electoral politics because nonwhite voters were disenfranchised. Race became much more central in electoral politics once nonwhite voters could all vote, which is a pretty recent phenomenon. What's happened in the last couple of decades, unfortunately, is that race has taken on a very clear partisan dimension. It could be that people of different ethnic groups were diffused equally across the parties. If both parties had both white and nonwhite people, they would fight about other things, but they wouldn't fight about race. Race is a fissure today because one party represents, quite clearly, a declining white majority and a threatened white majority.

The Republican Party is desperate. It fears that it is not going to be able to win elections, so bending and breaking rules to cheat their way into electoral victories becomes a preferred strategy. The rules that 30-plus state legislatures in the United States have adopted over the last decade have made it harder for people who are, by and large, lower-income nonwhite voters to register and to vote. That is deeply undemocratic. As long as the Republican Party is an overwhelmingly white and Christian party in a society as diverse as the United States, it is going to be prone to this kind of white-nationalist extremism. The Republicans must become a more diverse party.

Once this sort of extremism has taken hold, is it possible to repair the harm done to our democratic institutions and norms?

Levitsky: If in the fall of 2018 or in 2020 there is a shift to the Democrats, this, in principle, could prompt a reevaluation on the side of the Republicans to "refound" the party. Looking at cases around the world, in countries like Germany after World War II or Chile after Pinochet there have been efforts, after major catastrophes, for groups to reorganize themselves. It is difficult, but we don't really have any other options. It's probably naïve to think about going back to the norms that we had before. Probably we'll evolve in some forward direction, but it certainly did not have to be this sort of no-holds-barred partisan warfare that we've seen in the last couple of decades. If our democracy is going to remain even minimally healthy we need to develop a set of norms that allow our political parties to work through institutions.

What are you hopeful for about America's future and what are you worried about?

Ziblatt: One thing that I'm very worried about is the unwillingness of the Republican Party to, essentially, stand up and say, "Enough is enough." The reason that is so very worrisome is that, when one looks around the world and sees one of two major parties not accepting the rules of democracy and becoming ideologically radicalized, that is a fatal flaw for democracies. If you do not have a player who is willing to play the democratic game this also infects the other side, which results in a spiraling kind of dynamic.

Levitsky: It's very hard, really it's impossible, for me to think of a democracy in the world that survived an ethnic majority making a transition to minority status. There really has not been a successful experiment with multiethnic democracy in the world, and that's why the growing diversification of Western democracies is a real challenge. Looking at the reaction of the Republican Party over the last 10 or 20 years to these trends scares me a lot.

What gives me some room for optimism, and what makes me think that the United States has a shot to be the first successful multiethnic democracy, is that our democratic institutions are in fact quite strong. I think we did -- helped a lot by World War II -- a pretty decent job as a society of integrating immigrant groups that arrived in the late 19th and early 20th century. It was pretty nasty, it was hardly a model, but we did it. So as a society, we have much more experience with dealing with diversity and with integration than do other Western societies. That's how I put myself to sleep at night.

Shares