I can’t front: As a writer, winning a Pulitzer Prize is one of my dreams. Obviously that’s not the only reason I scribe, but how dope would it be to bring the gold medal back to my block in East Baltimore? Oh, and the $15,000 check would be nice too.

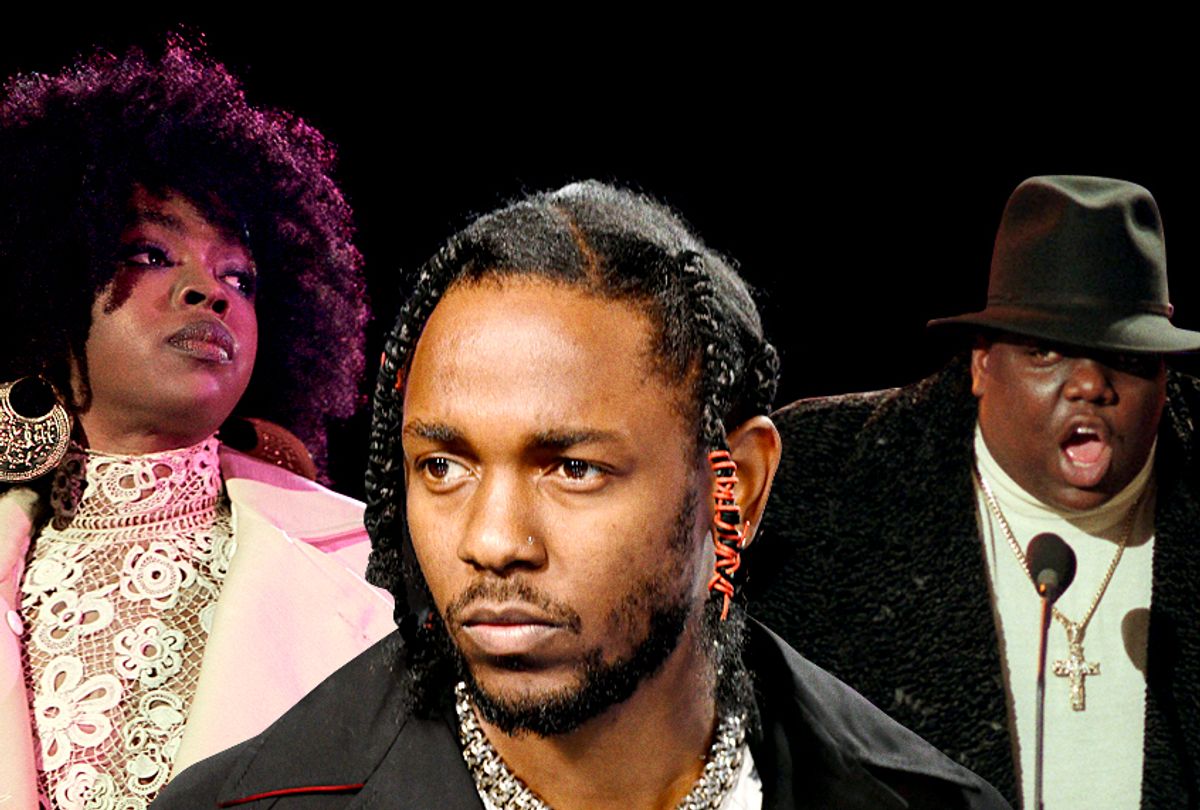

This week rapper Kendrick Lamar made history by being the first hip-hop artist ever to receive the prestigious award. The 30-year-old rapper was recognized for his critically acclaimed 2017 album "Damn" -- a collection of songs that documents love, family, religion, sexuality and financial fears against the backdrop of being black in America. Like so many others, I’m inspired by Kendrick and the success of his album. Some people feel that rappers should have been getting Pulitzers for years and it’s long overdue. I’m glad it finally happened and proud to see hip-hop get the respect it deserves.

As we celebrate the brilliance of "Damn," I’d like to throw out a couple of other albums that various hip-hop artists have put out over the years that were definitely worthy of the Pulitzer -- and perhaps got one in some other universe.

Nas: "Illmatic" (1994)

Before the days of YouTube, before artists were able to drop 10 to 20 mixtapes before ever releasing an album, there was Nasty Nas. The 19-year-old rapper from the notorious Queensbridge housing projects in New York set the rap world on fire with what many call one of the coldest lines in rap history on Main Source's "Live at the Barbeque," where he said, “When I was 12, I went to hell for snuffing Jesus.”

Not long after that, Nas signed a deal with Columbia and dropped the Pulitzer-worthy "Illmatic." Ten tracks consisting of one skit and nine bangers, including "N.Y. State of Mind," which sounded like Claude Brown’s "Manchild in the Promised Land" on wax to me; "Life’s a Bitch," a song that still cranks in the clubs more than 20 years later; and the epic "One Love," my generation's first look at the prison-industrial complex through the eyes of a family dealing with the pain of separation from incarcerated loved ones.

"Illmatic" changed rap, shifting the culture by incorporating complex narratives and visuals straight from the bottom of America’s most impoverished neighborhoods. Nas showed pain, had fun with his music and came off like a 'hood superhero at the same time with bars like:

Once they caught us off guard, the Mac-10 was in the grass and

I ran like a cheetah with thoughts of an assassin

Pick the Mac up, told brothers, "Back up," the Mac spit

Lead was hittin niggaz one ran, I made him backflip

Heard a few chicks scream my arm shook, couldn't look

Gave another squeeze heard it click yo, my shit is stuck

Try to cock it, it wouldn't shoot now I'm in danger

Finally pulled it back and saw three bullets caught up in the chamber

So now I'm jetting to the building lobby

and it was filled with children probably couldn't see as high as I be

Jay-Z: "Reasonable Doubt" (1996)

Before he was Beyoncé’s husband or owned a sports agency, apparel company, alcohol brand or luxury hotel -- before he was a multi-platinum rapper with 21 Grammys -- Jay-Z was Sean Carter, the crack dealer from the Marcy projects in Brooklyn. He had a few features with some no-name rappers and tagged along on some tours as a teenager in the '80s. Then he disappeared, only to explode onto the scene in the mid-'90s with his freshman album, "Reasonable Doubt."

Jay-Z showcased a flow and lifestyle that was foreign to mainstream rap. We were used to hearing our favorite artists sing ballads of brokenness, putting the struggles of being black in America upfront for everyone to see. Jay-Z started out rich. He rhymed about diamonds, Lexuses and Mercedes, showed them off in his videos and then pulled up in towns all over America with the same stuff he was rapping about.

Beyond its tribute to materialism, "Reasonable Doubt" is full of Pulitzer-quality stories about the heavens and hells that come with the drug game. Jay-Z used his firsthand experience to craft a masterful collection of songs composed of metaphors that blew even the most sophisticated listeners away. In "Brooklyn’s Finest," he rapped:

No more Mister Nice Guy, I twist your shit

then fuck back with them pistols, blazin

Hot like cajun

Hotter than even holdin work at the Days Inn

with New York plates outside

Get up outta there, fuck your ride

The line looks simple on the surface but Jay’s saying that he’s not playing nice anymore – he’ll kill you with a gun that’s hotter than Cajun food, hotter than stashing drugs at a small-town Days Inn with New York plates on your car parked out front. In three bars we get hot to the touch, hot as in spicy and hot as in drawing wild attention to yourself while you're committing any number of felonies.

"The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill" (1998)

The first lady of the Fugees exploded on the scene with the group's hit "The Score," dominating her male counterparts with the grittiest lyrics and leaving us all on edge waiting for her solo debut. Hill didn’t disappoint in 1998 when she dropped "The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill" – a 14-track mix of real rap dripped over beautiful songs full of love, clarity and profundity. (I feel like Drake stole her format, years later.) The album went on to sell more than 19 million copies worldwide and win five Grammys. Rolling Stone ranked it at No. 314 on its list of the 500 greatest albums of all time. (If you ask me, that's too low by a few dozen spots.)

In an era where women in hip-hop were often oversexualized, Hill came through with a cocktail of style, grace and soul that didn’t tell us young people how powerful, amazing and necessary women are -- it showed us. There are many classics on the album with songs like "Ex-Factor" and "Lost Ones," where she addressed the haters and manipulators:

It's funny how money change a situation

Miscommunication leads to complication

My emancipation don't fit your equation

I was on the humble, you -- on every station

Some wan' play young Lauryn like she dumb

But remember not a game new under the sun

Everything you did has already been done

I know all the tricks from Bricks to Kingston

My ting done made your kingdom wan' run

Now understand L. Boogie's nonviolent

But if a thing test me, run for mi gun

Can't take a threat to mi newborn son

L's been this way since creation

A groupie call, you fall from temptation

Now you wanna ball over separation

Tarnish my image in your conversation

Who you gon' scrimmage, like you the champion

You might win some but you just lost one

The Notorious B.I.G.: "Life After Death" (1997)

Biggie Smalls only lived to be 24 years old and you’d think he was a lot older than that after studying the complexity of his music. In the last three years of his life, he put out two of the best hip-hop albums ever created. Of the two, I think "Life After Death" easily deserved a Pulitzer.

This album won three Grammys that Biggie never got to see: He was killed about three weeks before it hit the street. It ranks at No. 476 on the Rolling Stone list, and the crew who rated it that low must have missed this verse:

Since it's on, I call my nigga Arizona Ron

From Tucson, push the black Yukon

Usually had the slow grooves on

Mostly rock the Isley

Stupid as a youngin, chose not to move wisely

Sharper with game, him and his crooks, caught a ?jooks?

Heard it was sweet, bout 350 a piece

Ron bought a truck, 2 bricks laid in the cut

His peeps got bucked, got locked the fuck up

That's when Ron vanished, came back, speaking Spanish

Lavish habits, two rings, 20 carats

He's a criminal

Nigga made America's Most

Killed his baby's mother's brother, slit his throat

The nigga got bagged with the toast, weeded

Took it to trial, beat it

Now he feel he undefeated

He mean it

Nothing To Lose, tattooed around his gun wounds

Everything, the game, embedded in his brain

And me I feel the same for this money ya dying,

Specially if my daughter crying, I ain't lying

Y'all know the signs

That excerpt is from the song "Niggas Bleed." Don’t worry, I’ll explain. The rap is in first-person from Biggie’s perspective. He was given a chance to make some money in a drug deal and recruited his friend, Arizona Ron, to help. Biggie explains why Ron’s the perfect guy to help pull off the caper in the second verse, where we get a glimpse of his brilliant storytelling ability.

Arizona Ron is from Tucson -- you probably figured that part out -- and drives a black GMC Yukon, a popular truck among street dudes, athletes and rappers in the mid-'90s. Ron was a gangster and liked to listen to the Isley Brothers. As a reckless youth, he robbed somebody (a "jooks") for $350,000, buying his truck and two bricks of cocaine with the proceeds. His partners from that caper continued to run wild and got locked up. But Ron vanished and returned later, speaking Spanish and with expensive habits. We can only assume that Ron made a lot more money somewhere in Latin America, because Biggie reports he came back wearing two 20-carat rings but also as a criminal who murdered his baby-mother's brother by slitting his throat. That makes Ron an experienced killer who is smart with money -- the perfect guy to do a heist with. On top of that Ron was incarcerated, didn’t snitch and beat the case. To celebrate he tattooed "Nothing to Lose" around his gun wounds. Biggie feels the same, because like Ron he’d do anything to succeed, especially if the ill-gotten gains help him feed his daughter.

"Life After Death" is like a street symphony full of Mafioso stories and humor -- it's honestly better than every Hemingway book I've read. Like Kendrick, Big definitely deserved a Pulitzer.

Maybe these big awards committees will do what the Nobel did for Bob Dylan and honor these guys in years to come. No award is needed to validate the music and lyrics on these great albums, but if Kendrick has now opened the door, I’m here for it.

Shares