Donald Trump needed a tax break. In 1981 he was in the process of building his second major New York City project, the Trump Tower on Fifth Avenue. As part of putting up the new skyscraper, he had applied to the city for an abatement of $20 million, which was intended to be a gift from the taxpayers given to developers for their willingness to build middle- or lower-class housing in areas defined as “underutilized.” But anyone who had ever strolled New York’s streets over the past five or six decades knew Fifth Avenue was hardly an underutilized area. It was as well-trafficked and upscale a slab of real estate as you could find anywhere in the country, let alone New York. On that basis, Mayor Ed Koch had instructed his administration to turn down Trump’s abatement application. Enraged, Trump called Koch’s housing commissioner, Tony Gliedman, and told him, “I am a very rich and powerful person in this town and there is a reason I got that way. I will never forget what you did.” When Trump called Koch to complain about Gliedman’s decision, Koch told him, “There is nothing I can do for you.”

Trump did what he best knew how to do: He sued. By his side was shark-lawyer Roy Cohn, who had made his reputation decades earlier as the top aide to Red-baiting Senator Joseph McCarthy but had since settled into a multitude of city roles: New York gadabout, manipulator of a wide swath of media sources, political kingmaker, and shoulder-rubber with the well known and well to do ranging from publisher Si Newhouse and conservative icon William F. Buckley to Barbara Walters and Norman Mailer. But he was still, mostly, a lawyer, and Trump had grown to appreciate the value of having a guy who could grease city wheels like Cohn on his side.

While Cohn was the big name, his law partner at the firm of Saxe, Bacon and Bolan was Bronx Democratic leader Stanley Friedman, and Friedman had the connections—as a boss of a borough political machine, he was heavily involved in the naming of judges across the city—that facilitated Cohn’s manipulations. Friedman found out Trump’s abatement case would start out in what was called Special Term 1 with Judge Frank Blangiardo, a twenty-two-year veteran of the bench who was an old hand at New York’s political gamesmanship. (Blangiardo would later be reprimanded for slapping the hand of a female attorney and saying, “I like to hit girls because they are soft.”) This was good news for Cohn, Friedman, and their client. Blangiardo was pliable. He knew Friedman’s power.

“You didn’t have to bribe Blangiardo,” New York Post court reporter Hal Davis said. “He was a hack. He was more than happy to do the bidding of the political bosses. When Cohn and Friedman saw that Blangiardo was getting the case, it was tailor-made for them.”

That did not mean Friedman or Cohn would be sitting before Blangiardo. They were the pullers of strings in the city, but they were not big on actual courtroom litigation. Cohn was not known to proffer eloquent legal arguments—you hired him because he was a blunt object with which to bludgeon your opponent.

Trump had a real estate lawyer who was to present the case, and during the opening session of the case, she handed Blangiardo two folders for consideration. One contained the usual legal documents. Inside the other was a statement from Friedman, at the bottom of which were two words and a signature that registered immediately with Blangiardo: “No adjournment. — Stanley Friedman.” When the lawyer for the city told Blangiardo she would need an adjournment to have time to put together a response to the filing, Blangiardo’s initial response was to parrot Friedman’s note: “No adjournment.”

He eventually acquiesced and granted a three-week adjournment, but only with the caveat that, in three weeks, he would be keeping the case for himself, a highly unusual step considering he was not scheduled to be in session at that time.

Despite the adjournment, the message from Friedman had been received—Trump was to get his abatement—and Blangiardo obliged. On July 21, the judge ruled in Trump’s favor. That was the power Friedman had, pulling strings with judges. Cohn’s power was a little different, but was evident the next day. Trump filed an absurd, $138 million lawsuit against the city and Tony Gliedman. Trump had no chance of winning, and the lawsuit was quickly tossed. But Cohn got the suit in all the papers, and in addition to Blangiardo’s abatement, he earned Trump, the hero builder and victim of an unjust city bureaucracy by Cohn’s account, a day of free PR.

This was not the first time the trio of Cohn, Friedman, and Trump had worked together to bilk New York taxpayers out of tens of millions of dollars for Trump’s benefit. As detailed by Village Voice writer Wayne Barrett, Cohn had taken on Friedman as a partner in his firm after Friedman’s tenure as former mayor Abe Beame’s deputy was up in 1977, and as one of his final acts in Beame’s office, Friedman pushed through spools of bureaucratic red tape to secure another tax abatement for Trump, this one for $160 million and covering his development of the Grand Hyatt at Grand Central Station. Once, at a lunch at 21 with a journalist, Friedman admitted, “Roy could fix anyone in the city. He’s a genius.” To which Trump added, “He’s a lousy lawyer, but he’s a genius.”

Ira Berkow had a bag of grapes on his lap as he sat on the twenty-sixth floor of the newly opened Trump Tower on Fifth Avenue in Midtown. When Berkow was growing up on the West Side of Chicago, his mother had taught him never to show up for a meal without offering a gift to the host. He was slated to meet with the building’s namesake, Donald Trump, in late 1983 to discuss the prospects for Trump’s latest venture, his purchase of the New Jersey Generals of the United States Football League, for an article in the New York Times. Before leaving for the interview, he had checked in with Trump, and Trump told Berkow he would order them some lunch—Berkow resisted at first, then said he would take a pastrami on rye and a Coke. But the lesson from his mother kicked in on the way to the interview, and Berkow stopped at a fruit stand. He paid $1 for the grapes. Dessert, he figured. That would be his offering to Trump.

Before being ushered into the office, Berkow—then forty-three and a relative newcomer to his Times column—was shown an eight-minute slide show, extolling both the virtues of living in the Tower and of Trump himself. “This is Manhattan through a golden eye,” according to the show’s narrator, “and only for a select few.” Condos in the building ranged from $600,000 to $12 million. Sports columnists are almost never considered among “the select few.” Berkow asked Trump’s secretary if he could skip the slides and see Trump. “Mr. Trump would like you to see it,” Berkow was told, in a tone that brooked no further protestation.

When he was finally inside, Berkow and Trump discussed his plans for the Generals. The USFL had gotten underway in 1982, with modest budgets and a chicken-wire-and-bubble-gum operating structure. The league derived its stability from its small-time aspirations. It played a spring schedule, offering ABC a safe run of television football programming away from the competition of the NFL and college football monoliths in the fall, and it was dedicated to bringing in low-dollar talent without sparking a salary war it could not win against the NFL. Its major attraction was running back Herschel Walker, signed to a three-year, $5 million contract by the Generals, before Trump’s arrival, as a junior out of Georgia.

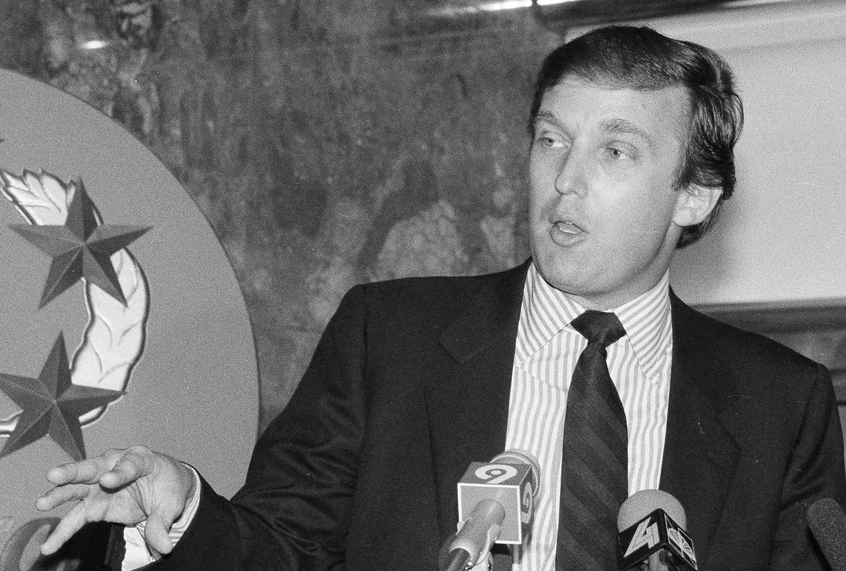

But in just two-and-a-half months, Trump had blown away the USFL’s cautious model. Two days earlier, he held a press conference to announce the signing of former Browns quarterback Brian Sipe to a two-year, $1.9 million deal. He had, back in October, gone through a delicate dance with Dolphins coaching legend Don Shula, who was said to be unhappy in Miami and had engaged in discussions about the Generals job. Word of the talks leaked to the papers, with Trump said to be offering $5 million for five years.

That leak—Shula was certain it had come from Trump—was the first blow to Shula’s potential signing. The second blow was another leak, a story claiming that Shula would only take the Generals job if he would be given a condo in Trump Tower.

Shula had made no such claim and, irate, he backed away from any further Generals negotiations. “I can assure you,” Shula said, “that my price is not a condominium.”

Trump instead made a more modest, but still competent hire, signing former Jets coach Walt Michaels. Truth was, he was never going to hire Shula, but he was interested in the illusion that he might hire him and the attention it brought him.

After the botched Shula negotiation, a USFL executive contacted Trump to tell him how upset Shula had been about the Trump Tower story, and that it caused Shula to walk away altogether. Expecting contrition or at least frustration, the official instead got Trump smugness. “Hey,” Trump said, “is that great publicity for Trump Tower?”

Trump had done much the same with Giants star linebacker Lawrence Taylor, who had not been particularly happy with his contract in New York but had little recourse to change it. Taylor had an option in his deal, but it was not slated to come until 1988. So Trump did something unusual—he signed Taylor to a future deal, promising to pay him $2.7 million over four years once his NFL contract was up. But Trump also left an option for Taylor to renegotiate with the Giants if he so chose, as long as Trump’s end of the contract was bought out.

The move was all three-card monte, of course. The option year was still far off, and there was no doubt the Giants would renegotiate with Taylor rather than risk losing him. There was virtually no chance Taylor would play for the Generals. But Trump got what he wanted: attention.

Berkow asked him about the rumors of him signing Taylor. “No one knows if we signed him,” Trump said. “Actually, only three people know, that’s Lawrence, his agent and me.”

The Generals, at the very least, served that purpose for Trump. They got him some headlines. For Trump, fame and power were interchangeable, and the Generals brought him fame.

“I hire a general manager to help run a billion-dollar business and there’s a squib in the papers,” Trump told Berkow. “I hire a coach for a football team and there are 60 or 70 reporters calling to interview me.”

When they finished their lunch, Berkow put his bag of grapes on Trump’s desk. He told him what he had paid for the dessert, and knowing he might be mistaken for a cheapskate, Berkow said, “You know, Donald, this lunch has had a bigger relative impact on my bank account than yours.” Berkow thought his joke might draw a laugh or at least a chuckle from Trump. It barely drew a smile. Later, Berkow said that in twenty-plus years of interactions with Trump, “I don’t think he ever laughed once.”