You’d think Mayim Bialik would be a natural expert on the subject of boys. In her two iconic television series — “Blossom” and “The Big Bang Theory” — she was surrounded by males. She earned her PhD in the male-dominated field of neuroscience. And she’s the mother of two sons.

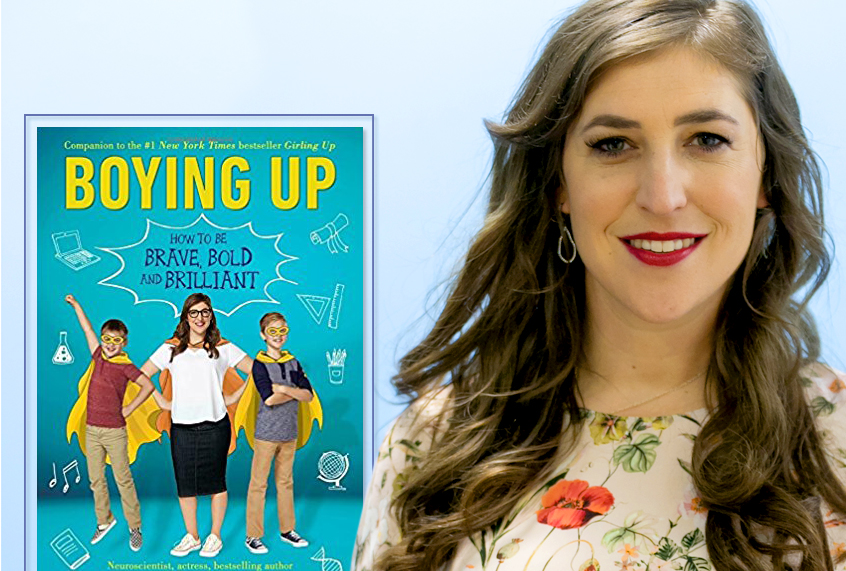

Yet when she set out to write about growing up, she first tackled the female perspective in her book, “Girling Up: How to Be Strong, Smart and Spectacular.” But now she’s back with “Boying Up: How to Be Brave, Bold and Brilliant.”

She talked recently with Salon about what she learned while researching the boy brain and why she’s optimistic about the new generation of kids growing up now.

I want to take a step back, because you are a mom of boys. You describe yourself as a rough and tumble kind of a lady, and yet you chose first to tackle the subject of girlhood. I want to know why.

I first tackled girling up, or the process by which girls become women, because I wished that I had had that book as a child. It really didn’t occur to me at all to write from the perspective of a parenting guidebook, because even with the first book I wrote about parenting, I don’t really know how to parent other people’s kids. I know what I do with mine, and sometimes I’m right and sometimes I’m wrong. But it wouldn’t have occurred to me to write a book about what it’s like raising boys because that wasn’t the perspective I was coming from. I was coming from this perspective of, “I wish I knew then what I know now” about biology, about psychology, about women’s place in society, so that’s why I started with that.

On the book tour last year, people said, “Are you going to follow it with boying up?” And I thought, “Of course not. Why would I do that?” Then I realized, “Oh, I’m a neuroscientist. I also was trained to understand the male body and male psychology and all of those things.” As a mom of boys, I tend to like to think that I know things, but I really don’t, even though I’m a rough and tumble kind of mom. I’m what used to be called a tomboy. I don’t usually look like this. They still confound me, and there are ways to try and learn to understand them better.

Watch our interview with Mayim Bialik

A Salon Talks conversation with the “Big Bang Theory” star and author of “Boying Up”

One of the things you do in this book that I am so grateful to you for, Mayim, as a mother of daughters, is you talk about girls. And a lot of that conversation is lost on boys. Girls and women are brought up to understand men and boys, and what we can do for them and to get inside their heads, and understand them and their brains and their bodies. And boys are not given that knowledge.

Right. And I think we kind of explain it away with, “Oh, you know, boys aren’t interested in that. Boys won’t want . . . boys will be grossed out.” My feeling is, the more we normalize talking about body functions and body parts, the less stigma it has and the less we have to, as a society, keep protecting boys from information that they should have and learn to be comfortable with from an early age.

So, while my boys don’t love knowing about what a menstrual cycle is, a lot of it, and I talk about this in the book, is how to communicate information the way boys tend to want to receive information. So, with that kind of stuff, you’ve got to get in, you’ve got to say it, you’ve got to get out. They don’t want a whole essay of the beauty of the menstrual cycle. They don’t need to know that, it’s true. And a lot of girls aren’t interested in that, either, but I do think it’s important. “Girling Up” included things about the male body, and “Boying Up” includes things about the female body.

About the female body, and about the female mind and about consent.

Right.

And you really get into having a conversation that understands we have to figure out how to communicate with each other and we have to figure out how to understand each other and coexist with each other, instead of being in our corrals.

Exactly. And I think a lot of it, also, is that we get caught up in these stereotypes and in most cases, they are stereotypes. This notion of “locker room talk,” which honestly our president introduced into our vernacular in a way that I did feel deserved addressing in “Boying Up.” I specifically address, “What is locker room talk? What does it mean to talk about women when they’re not around? How does it change the way we think about them?” And I think that’s part of what you’re touching on. We need to keep communicating, and it’s not too early to start with boys when they’re tweens, which is really when this book starts.

Let me back up and say that if you haven’t opened this book yet, you really should get it, look at it, peruse it. It’s full of illustrations; it’s full of sidebars where you hear the voices of boys themselves.

The “That’s What He Said” box, right?

And men themselves. It really is a book that you can sit down with your kids and share with them.

Right. It is true that in the 10- to 18-year age range, girls tend to read more this kind of book than boys. However, there are boys who can, should and may want to read this book, but it really can be used as not a suggestion or advice book, but as a guideline for how to open up conversations and also how to frame conversations with boys in ways that are comfortable for them. A lot of boys need to process big things alone, and that’s not a personal attack on you as a parent if they don’t want to talk a lot. But being able to communicate succinctly, especially about things with emotional content, is a very specific way that boys often want to be communicated with.

This must be so fascinating to you, as a neuroscientist, because we talk a lot about gender, and of course there are so many issues around it in our culture right now. There’s such a difference between equality and sameness.

Sure.

You really get into what the biological differences are and what the differences are in our bodies and in our brains.

Right.

Talk a little bit about that. One thing I thought was really interesting is the explosion of diagnoses of ADHD and why that may be a gendered assessment.

I think it’s absolutely very important to acknowledge that, generally speaking, there are differences in anatomy, obviously, and the Y chromosome has different things on it than that second X chromosome that girls will get when they develop when they are babies. There are psychological components that come because of the biological things that occur on that Y chromosome and in a male body. A lot of people think, “Oh, it’s just a chromosome. Everything else should be the same.” But the fact is, our genetics do determine a lot of the other things about us. Again, these are generalities. I talk specifically about people who have different chromosomal situations, or men who fall on the feminine spectrum, or women like me, who tend to fall more on the masculine spectrum, that all of that is normal, accepted and should not be denigrated. I talk a lot about that, in particular about bullying and things like that.

But the second part about the ADHD, yes. There’s absolutely discussion in legitimate scientific circles about the rise in diagnoses and the fact that the proportion of male teachers has fallen so steeply over time that there may be some sort of bias against what is generally kind of normal boy behavior, to not want to sit still and to be all over the place and climb and things like that. That’s not true for every boy and it doesn’t mean that there aren’t girls who are also like that, but we do see a lot of those diagnoses and there should be some caution with which we medicate children to the amount that we do, especially for ADHD.

And you talk about it. You make it very clear that this is not every kid in every situation, but you also get into the statistics of what the numbers really look like right now. What is it, 3 percent [of kindergarten teachers are male]?

Yeah. We have to be careful. We can’t just blame increased diagnoses on us being over-vigilant, because the fact is that there are also aspects to diagnosis that we didn’t know about ten years ago, 20 years ago, 50 years ago. So, we have to be careful with that, and as a scientist, I’m trained to be careful about that, and I really try to be careful about that in this book as well.

Because the sophistication of assessment keeps evolving.

Changing every day.

I want to know how this has changed you as a parent. You come into this with a wealth of knowledge and understanding and you get to have the comma, PhD, at the end of the book, and yet I’m sure you also had things about this experience that surprised you.

Absolutely. I think that the fun about getting to talk about this book is that as much information as I came into it with, my boys are at the age where I know nothing.

They’re nine and twelve.

Nine-and-a-half and twelve-and-a-half, yeah, so we’re nearing tween-ness and teen-ness. I think that one of the things that I learned best and realized best as I was writing it is that a lot times, my needs can get in the way of communicating effectively and efficiently with them. For example, if something’s upsetting, my solution is, “Let’s talk and hug it out.”And a lot of times my children do not want to be touched when they’re upset, and they often don’t want to talk. They want to process in quiet, and then return later for a very quick summary conversation about what they were upset about and what we can do about it. I’ve found that understanding that an organic process of being male, which I do think a lot of that is, has allowed me really to back off and give them that space, which I think allows them to return to communicate more.

Whereas my tendency would [be] to pursue and to nag and be that annoying mom, which I’m already afraid that I am. I think that part of the process of me writing this book and putting it all down was realizing, “Wow. It’s not about me. It’s about what’s the best way to facilitate their growth and their development in ways that are respectful of their organic processes.”

It’s really exciting to see a book like this out there in the world because the past several years, there has been this shift and there have been a lot of conversations about how we’re raising girls and what we need to teach our girls, and how we need to raise them up to be leaders in the world, and how we need to encourage them in STEM and all of that.

Which is so important.

Which is so important. I’m a mother of two girls. I’m all for all of that, but what has been neglected, or put more to the side, has been this conversation about how we’re raising boys. It seems very clear that that has not been great for any of us.

No, and I think also what we’ve seen in the last year unfolding in our culture, not just the Hollywood industry but other arenas as well, is that we can’t and shouldn’t dismiss a lot of things as “boys will be boys.” It’s time to stop dismissing things as “boys will be boys” and that’s something I talk about specifically in the book. What does that mean? A lot of times, it means accepting unacceptable behavior because we think we don’t know what to do about it. And the fact is, we do. We can do better, and we need to do better for our boys and also for the girls and the boys that they will interact with.

Right. And it’s not the job of girls to police that, or fix that.

No, we need to start earlier. We need to start earlier, and we need to be more explicit, and I think part of it starts with not accepting unacceptable behavior even from the time that they’re little.

I wonder what it felt like for you as a mother of kids who are still at that age where everything is just, “Nah, I don’t want to hear about it,” and there you are. You’re talking about contraception. You’re talking about erections. You’re laying it all out there, Mayim.

Well, there’s an age appropriate way to do that, also, and so I do recommend if kids are on the younger end of this kind of age spectrum, that it is something that I recommend that parents go over first and decide where their child is kind of ready to get that information.

Right, because it really spans the gamut.

And every family’s different.

The beginning of adolescence to contraception.

Yeah, which I’ve been told is actually a conversation that needs to happen younger than even I expected, or even than was expected when I was a teenager, so that’s why it has to be in there.

That’s why it has to be in there. It’s like the HPV vaccine. Let’s have these conversations before kids become sexually active, so that they come into it with their eyes open and armed with information.

Right, and in an age appropriate way. Absolutely.

You really also are very clear in this book, and I want to commend you on this, about saying every family is different. We all have to figure things out for ourselves, whether it’s about your sexuality, whether it’s about gender identity, whether it’s about the choices you make in diet and exercise, right? I want to also ask you how you made these choices, because boyhood is a big, huge topic and this is a very economical book. You really get in and out.

It’s funny because I went through the same thing. Jill Santopolo, who is the editor of both these books at Penguin, I talked a lot in “Girling Up” and continued that conversation in “Boying Up.” It’s not a political decision or a series of decisions that I make so that it’s marketable or palatable. What I really wanted to do was present the information that I think all boys deserve to have and that all families deserve to have, as a way to have conversations. But then there’s going to be a lot of variability depending on your religion, your political affiliation, the culture that you’re raised in. There’s going to be so much variability.

I think that what we all should work for, and what I do at my website Grok Nation, is try and present information so that everyone knows where everyone else is coming from. But it doesn’t mean you have to agree with them. I think we’ve become so fixated on, as a liberal person, “Oh, a liberal person wants everyone to think liberal things.” But the fact is, what it really should be about is us sharing information and being able to have complicated conversations even if we don’t agree. That’s going to come up with your kids, too.

And being exposed to different information and different points of views and understanding that you can have that happen in a way that is not threatening to your own perspective.

Yes. God bless the millennial generation. We’ll see if we can do it.

That’s another thing I wanted to ask you about, because now we’re moving into this. Both of us are parents of kids who are not millennials, and that’s scary and exciting in its own ways too. And I’m wondering, what has given you hope? When you look at your kids, and you look at the kids around them and you see all of the challenges and all of the frustrations and all of the craziness they bring to our lives, Mayim, what makes you think, “Maybe you’re going to be OK?”

You know, the fact that my boys like to have short haircuts gives me hope, but like, maybe we’ll return to the days when everyone wore suits and ties but with more of a progressive modern perspective.

And hats.

Exactly. Little fedoras. No, I think . . . I have a lot of hope. I’m an old school feminist who really believes that women have a very unique and special place in society and the ability to improve the lives of those who are affected by race, class and gender disadvantages. I really do have a lot of hope in the women and the young women and the girls of this next generation. I love interacting with girls my kids’ age who already have such a strong sense of themselves and already have really strong opinions about what they should wear, what they should be allowed to wear. The conversations that you can have even with five- and six-year-old girls really give me hope that this is the next generation of girls who can lead a movement on their part that can be better for men and for women, which is what the original idea of feminism was. That gives me hope. And there are so many sensitive, interested men, boys and young men who are transitioning to manhood who I believe will carry on good things for the next generation, again for women and for men.

We’re all in it together. One more question I have to ask you because you are on a little TV show that some of us may have heard of called “The Big Bang Theory.” You are surrounded by males in this show.

It’s like academia as a scientist. It’s not that different.

It’s like a lot of things, right? So, writing this book, did it change how you look at the characters? Did it make you start assessing them a little differently?

Not really. I think that when I wrote “Girling Up,” I got to talk more directly about what it’s like to be a scientist and play a female scientist on television, so that’s more a part of “Girling Up.” But it’s in there also, with “Boying Up,” just because of my placement as a mom and as a scientist, again, who still felt pretty clueless about a lot of things about boys. I think that, generally speaking, the men on “Big Bang Theory” walk a fine line between immature and mature. But we try and present our scientist women really positively, and I think with Melissa Rauch’s character and with mine as the two scientists on the show, we hold our own pretty well.