Author and former Salon columnist Ellen Ullman wrote her first computer programs in 1978 and spent 20 years as a programmer and software engineer. While Silicon Valley is not exactly known for being a gender-equal place nowadays, it was even less so back in the 1980s, when Ullman was just starting to work in a nascent industry whose cultural and social mores were still being litigated.

Simultaneously to working as a coder, Ullman slowly started building a reputation as one of the most insightful and poignant thinkers on the subject of the tech industry. In contrast to much tech-insider writing, Ullman is poetic; reading her, you get a sweeping sense of the emotional and meditative practice that comes with being a coder.

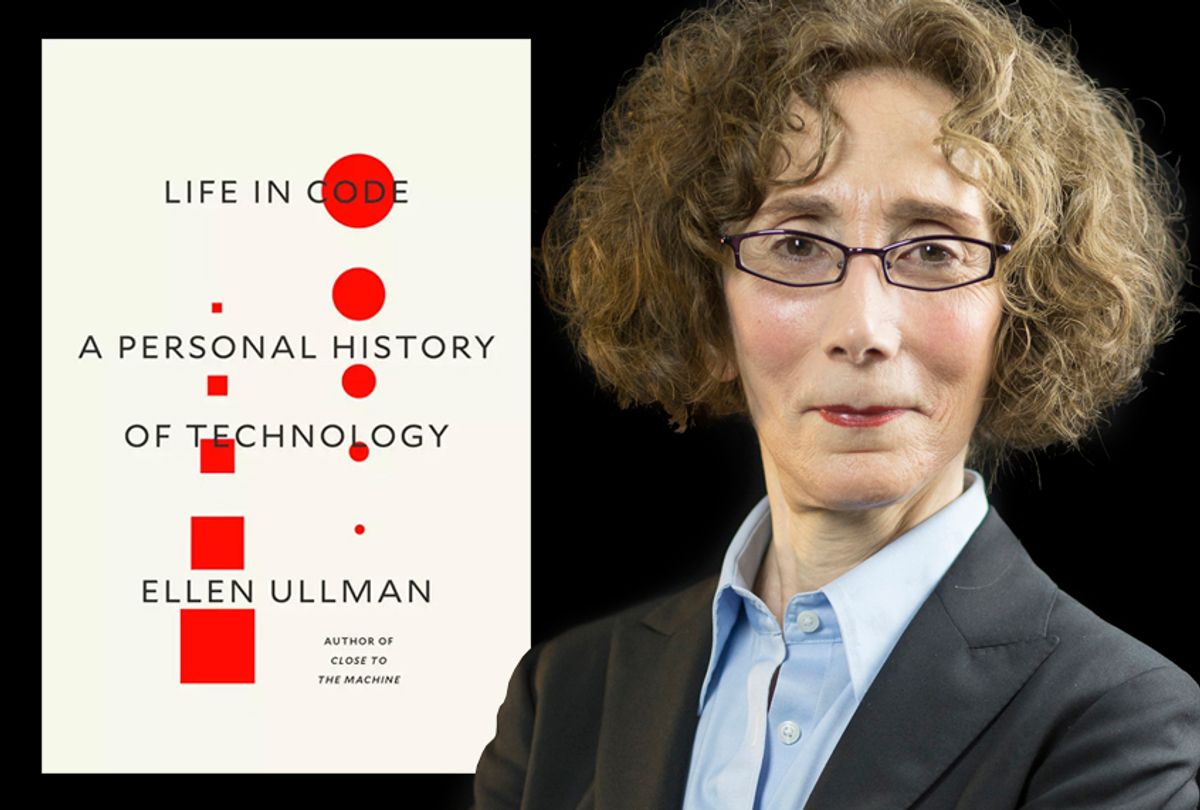

Accordingly, Ellen Ullman's prior books have become landmark works describing the social, emotional and personal effects of technology. Recently, Ullman sat down with Salon's Alli Joseph to discuss her new book, "Life in Code: A Personal History of Technology," as well as what it was like infiltrating the boy's club of the tech industry. This interview has been edited and condensed for print.

Alli Joseph: What was the technology landscape like when you came to the scene? Were there many women?

Ellen Ullman: I have to tell you, the first scene I was involved in were a bunch of crazies — Stewart Brand and company who form the Whole Earth 'Lectronic Link, "The Well," which I'm still on. [Editor's note: The Well was owned by Salon for a span of about 10 years.] People came to it from different walks of life. I worked with a former Sufi dancer, someone who had ABD in art history. It wasn't an engineering culture. People came because they were excited about it and had a passion to do something, make art, do social change. The first motives were exciting.

Then at some point, and I'd say the early to mid-'80s, computer science became a department of its own. It had been a sub-branch of electrical engineering, and suddenly my colleagues had BAs or advanced degrees in computer science and engineering. The whole tenure of the place changed. It was very heavily male, a culture of young men, mostly ones who were pre-adult in their lives, did not have a lot of family responsibilities yet. I was slightly older because I had spent my time experimenting and running wild and this was for me, a way to make money. I never expected I'd spend 20 years doing this, never. It was, my friends who knew me from college days were shocked. "You became a what?"

Joseph: I think it's important to note that you're self-taught in coding. What made you interested in it?

Ullman: I worked with a group back in the early '70s that was doing video. The coming of the Sony Portapak [marked] the first time you could make videos. It was like the coming of the PC, there were these huge corporations that controlled broadcasting, and then suddenly you could make your own videos. You could make art with this, you could experiment ... so I learned, wow, I liked working with machines. This is fun, I like learning how to use all the decks and all the sync generators and cabling up.

A few years later I moved to San Francisco. I was walking down Market Street and there was a TRS-80 and early microcomputer in the window. I went, I don't know, is it anything like a video machine? What can you do with it? And I bought it without any premeditation and then said, "Oh God, there's something called programming. Oh, I guess I'll figure that out."

Joseph: You mentioned that there were so many men that did help you along your journey. Let's talk about being a minority in the industry in the late '70s and early '80s. What was it like for you?

Ullman: I did work in a couple of companies. [At] my first jobs there were women, who came from various backgrounds who did have technical jobs... that made it much easier. A woman stands out — you can't be just good. You have to be the best. Every flaw, every mistake you make — it's like you're just a dumb girl, you don't know what you're doing. I faced a lot of that, but there were men who were very helpful and sympathetic.

As I moved on to do C coding and got closer and closer to the kernel of the operating system, it got complicated. Without a computer science degree, I had to learn on the job. Many of the men that I met were so helpful and fun to work with.

Joseph: You mentioned that there were certain good places to find bugs in code?

Ullman: The shower, showers are great for bringers of bugs. If you're a writer or [in a] creative field, don't you have a pad outside of your shower that's perpetually wet, dripping writing?

Backing away and appreciating something else in life is key to the whole process of coding. It's immersion and focus and then back in the car.

Joseph: You've written other books before specifically about your experience coding at that particular time. Why do a book of essays now originating in 1994 to present — why did you want to produce a book like this?

Ullman: I want to say there are many people who have been in the industry much longer than that. Why do this? One was the encouragement of my editor, Shawn McDonald, and he said, "Look, this is a perspective in time. People are looking at technology now and seeing Facebook and seeing journalists and experts being cut out by a president of the United States, the disparagement of expertise."

I can say, well, look at 1996 and 1998. We saw the beginning of this process, something called disintermediation where’s like, just come to the web, get rid of all those intermediaries. You don't need them and you and the webpage and nothing in between. Taking out even artists, curators, journalists, writers, anyone with intellectual or artistic or even financial expertise kind of wiped out the center. You can see how that's an arrow shot in the air and landed at the feet of Donald J. Trump with Twitter. Completely going over the heads of everybody, the entire government of the United States. Even his own, I don't know, judgment, if he ever gives pause.

Joseph: It truly is bizarre to see the president of United States using Twitter in the manner that he does, without any controls.

Ullman: It's disparaging, I really don't want to hear what somebody is saying that off the cuff. This is a discouraging world to me now. I don't participate because it's too interruptive. I mean, coding, writing require focus and turning off the phone. Email is a little devil with a pitchfork. Getting away from those interruptions is one part of life. I do look at it, see I'm being… I look at it as a social phenomenon. I think seeing what's trending is interesting from a social point of view, but as an individual, as a human being, I'm not interested in it.

Joseph: You were immersed in tech as the internet gained popularity as you mentioned, and we started to see these tremendous excesses, which I also saw at companies like Prodigy and AOL. At some of the magazine publishing houses and many others, many of which are gone today. Then there was the web 1.0 bubble bursts around, 2000 to 2002-ish and things got really quiet and there was this dissonance that I think people who had come to the industry as entrepreneurs and made buckets of money and then lost so much really didn't know how to process. What were your thoughts on what would become of the tech space at that time?

Ullman: There is a chapter in the book that talks about that burst, in which companies were valued not because they were going to make money — most of these had no prospects of becoming profitable. It was eyeballs, revenue stream, people jumped in and then the general public jumped in, the proverbial shoeshine boys of the depression who were buying stock. The general public got fleeced, no, this whole bandwagon, they jumped on late and then the crash came, the smart money out, surely some of the investors lost money. They were rich people and they knew the risks involved, but the public had their pockets picked.

I'm afraid something like that is happening again. [Again] we have companies that don't make money. Uber in one quarter lost $645 million, and that was an improvement on past performance. How much is it valued at now? But it's private, and I worry more about the fact that it is being controlled by a bunch of people determined to make billions and therefore are pumping up these companies. If I look at these two time periods, boom one, boom two, I get very worried.

Joseph: We're inching our way toward another crash. You could say because of the potential for loss and, and the lack of value proposition.

Ullman: There are companies that have a lot of value. Apple has value, Microsoft has value. These are companies that are not going to disappear.

The others, all these startups that are in this — WeWork, Space... I walked around my neighborhood one day, I did like three square blocks and I counted, I don't know, perhaps 75 startups with, really weird names like "Weebly."

Joseph: Oh, Weebly.

Ullman: Most of them are gone now. If I took that same [walk] around there, they're gone. I fear that there's a whole generation of people who barely know life before the internet or never knew life before the internet and are being swept into this startup fever. I worry that, oh, they'll lose their money. They'll lose their professions. They will have disappointment.

They will likely be disappointed if they're in it for the experience. I fear that many [in tech] have an idea that they're changing the world somehow for the better and I am very skeptical of that mantra.

Joseph: There's some statistic I read recently about millennials being the generation that has been most concerned with their work having meaning. Many of that generation is indeed working in tech. Maybe there could be a happy medium. Could there be a compromise? Not a Malcolm Gladwell tipping point, but like a place where you can do both? Can you have both?

Ullman: I certainly hope so. I'm not a futurist. I mean some of the things I talked about 20 years ago have come true and I'm very unhappy about that, but I don't know what will happen [in the future]. I think it's up to them. There was a whole new generation that is working in tech. They are controlling the future and I look to them, they have to tell me. I can’t predict what they will do. It's their turn.

Joseph: You were both an insider as a tech mind and also an outsider when you began as a woman in technology. Technology has kind of a closed culture as you've talked a little bit about, but you've written that you'd like to see it open up — go beyond wealthy men to include programmers from different ethnicities, different fields of study and economic standing, right? What steps can the technology industry take to improve upon that and make it an actual reality? Is it more self-teaching?

Ullman: It's not the technology industry. People have to form groups. It has to come from the ground up. I don't see that Google's programs are going to work — they may engender fierce backlash. Every time I have witnessed these, "let's welcome people in to these big corporations," the backlash is fierce.

I think it has to come from the ground up. Community organizations, corporations can do their part, but this idea that they'll be a special group identified as needing help, there is this reaction, "Well, can't the bitches make it on their own?" Yes, we have to go off and make it on our own.

Joseph: You heard it here. We're making it our own as we should, last bit. So what's the best piece of advice you received and what you would give to young women and girls who want to be coders or programmers?

Ullman: First of all, learn if you really want to do this. You have to have a passion for this. Writing code is putting in bugs and then removing them one by one by one, and so [you need] a certain pleasure for the hunt. A certain sense of being seduced by this difficulty — otherwise it's not for you.

Not everyone has to become a professional coder. Learn it to the extent that you demystify algorithms. You know people wrote them and they can be changed, but then know that you are going to face prejudice, period. No matter how good you are, how much help there is around you. There's going to be prejudice. You will have to face it, to look it in the eye and just lean into that pleasure and that knowledge that you really want this and will not be turned away. That's my advice.

Shares