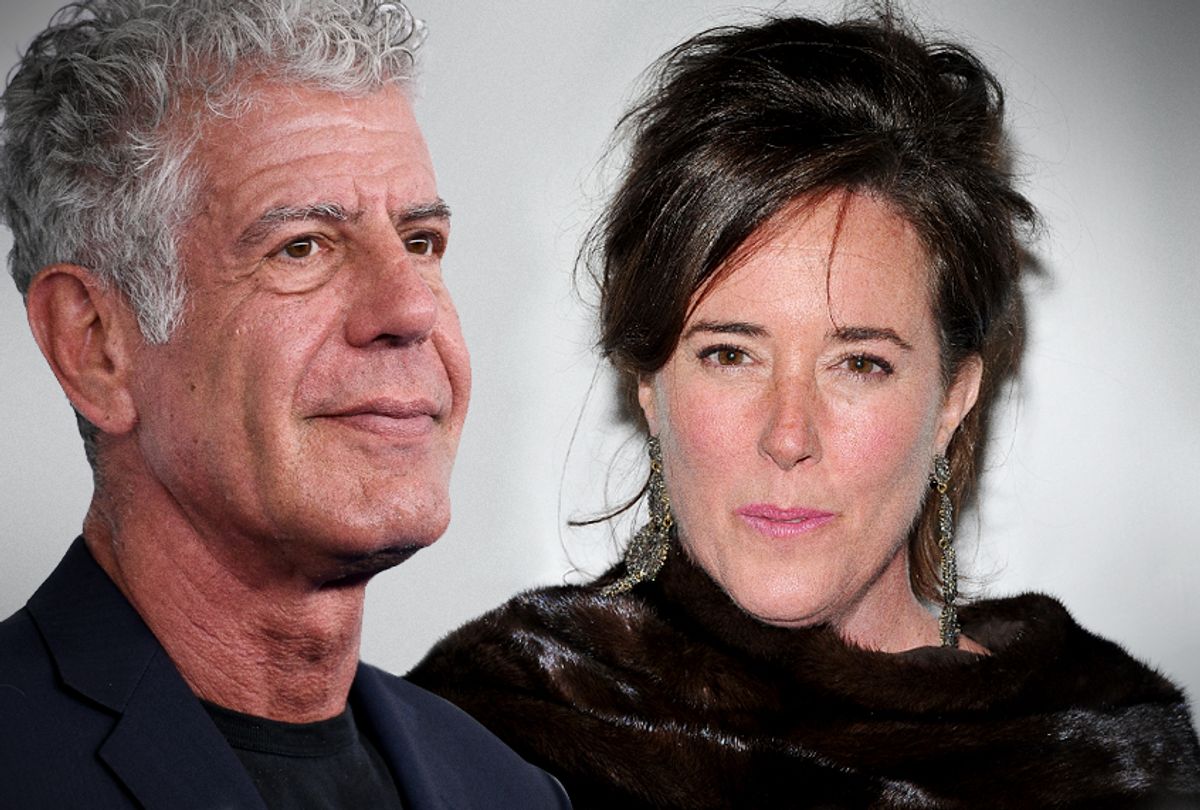

The recent deaths of fashion designer Kate Spade and celebrity chef Anthony Bourdain have forced the media into a necessary, albeit painful, discussion of suicide and mental illness.

According to a new study released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, suicide rates have been rising in nearly every state over the past two decades. It is now the 10th leading cause of death, making it a critical U.S. public health issue.

How the media portray suicide directly affects how our culture handles it, and the stakes for irresponsible reporting are high. As the CDC states, the phenomenon of copycat suicides, or suicide cluster or contagion, can result from simplistic, sensational and glamorized coverage. One notorious example, cited by the Suicide Prevention Resource Center, occurred in 1962, when the month following the death of Marilyn Monroe and the ensuing media circus saw a 12 percent rise in suicides. (“The blond, 36-year-old actress was nude, lying face down on her bed and clutching a telephone receiver in her hand when a psychiatrist broke into her room at 3:30 a.m.,” was how the Los Angeles Times broke the news.)

A 1990 study in the American Journal of Public Health used state records from 1978 to 1984 to identify clustered suicides — three to 11 incidents that occurred in the same city or town in a three-month span — and analyzed news coverage of the events. The study found certain story characteristics, including front-page placement, headlines containing the word “suicide” and descriptions of the suicidal person and act, appeared more often in reports on the first suicide in a cluster.

Guidelines for reporting have been drawn up. But in the wake of Spade and Bourdain’s highly publicized deaths, some corporate media have failed to follow them, apparently willing to put ethics to the side in their quest for clicks.

The Society of Professional Journalists’ Code of Ethics, the fundamental guidelines for U.S. journalism since 1926, states that reporters should “minimize harm,” explaining that they should:

- Balance the public’s need for information against potential harm or discomfort

- Weigh the consequences of publishing or broadcasting personal information

- Avoid pandering to lurid curiosity, even if others do

Mental health organizations such as the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (AFSP) have issued advice to journalists on minimizing harm in reporting on suicide.

One of the AFSP’s recommendations (adopted by the 2015 revision of the AP Stylebook) is to abandon the word “committed” in relation to suicide, substituting phrases like “died by suicide” or “took his/her own life” instead. J. John Mann, a psychiatry professor at Columbia University and a past AFSP president, explained on Democracy Now! that “committed” implies suicide is a crime, perpetuating stigma:

Suicide was regarded as self-murder. There’s a long theological background to this kind of thinking. And so this was a terrible problem in terms of reaching out to these people and offering them help. We know now in many religions that the theological view of suicide has changed. It’s now regarded as the act of an ill person, and therefore not a sin, and thus people and their families should be treated just the same as people who have died of any other cause.

While most major news organizations have caught on, to their credit, the New York Post (6/11/18) and the Boston Globe both used the phrase “committed suicide” when discussing Kate Spade’s death. The Economist published an obituary headlined, “Anthony Bourdain Committed Suicide on June 8.”

The AFSP also advises that although sharing up-to-date suicide data is an effective way to shed light on the issue, reporters should not refer to suicide as a “growing problem,” “epidemic” or “skyrocketing,” as these sensationalistic terms have been shown to cause contagion.

While on Democracy Now!, Amy Goodman asked carefully about the “rising rate of suicide,” other publications have not been as cautious with their wording. Newsweek reported, “Suicide rates in the US have spiked by 30 percent since 1999,” while a Houston Chronicle article read, “Celeb Deaths Spotlight Suicide Rate Spike.” The New York Times published an opinion piece by Richard A. Friedman, a psychiatrist, which addressed an “alarming” “suicide epidemic.”

Additionally, according to the ASFP, a reporter should never refer to a suicide attempt as “successful,” “unsuccessful” or as a “failed attempt,” as the word “successful” has a harmful positive connotation. Most outlets avoided this terminology.

However, the Houston Chronicle stated: “In all, there are about 1.3 million attempted suicides annually. Only 1 in 25 are successful.” A Providence Journal editorial warned that many who attempt suicide “will try to do so more than once. Some will eventually succeed.” (The Journal editorial also noted that guns “were used in slightly more than half of successful suicides in 2016.”)

Also warned against: graphic or glamorized depictions of a suicide death, including details or images of lethal means or method used, details about location, and the sharing of notes left behind. Failing to follow these guidelines, the ASFP asserts, increases the risk of suicide contagion. But several outlets ignored them.

Many outlets referred to Spade’s and Bourdain’s suicides as “deaths by hanging,” but some went into further detail. CNN’s Eric Levinson and Brynn Gringas, for example, wrote, “Spade was found hanged by a scarf she allegedly tied to a doorknob, an NYPD source said.”

One can fault police for divulging such information, but media outlets are in charge of what information to share with the public.

CNN was only a step above tabloid TMZ, which published, “We’re also told the housekeeper found her tied with a red scarf to a closet door knob in the bedroom.” Did readers really need to know the color of the scarf Spade used?

Rolling Stone gave a similarly unnecessary description of Bourdain’s death, detailing that he used a bathrobe belt to hang himself. The New York Post, in an article picked up by FoxNews.com, also shared the gratuitous detail that Bourdain “hanged himself with the belt from his hotel bathrobe.”

TMZ also shared the contents of Spade’s suicide note to her 13-year-old daughter, even displaying it in the bold font of the headline. The New York Post’s PageSix also published the entire note.

Both outlets failed to include mental health helpline information anywhere in their articles, a practice ASFP also advises.

Though no one expects tabloids like TMZ and the New York Post to be pinnacles of journalistic integrity, they are widely read. In the last six months, TMZ’s website had nearly 50 million visits, and the New York Post had almost 89 million.

Spade’s family expressed anger over the note being shared. Her husband, Andy Spade, said in a statement to the New York Times that the note was shared to the media before it was shared with Spade’s family. “I have yet to see any note left behind and am appalled that a private message to my daughter has been so heartlessly shared with the media,” he wrote.

Although the Times did not publish the note verbatim, it did paraphrase it directly:

A police official, speaking on the condition of anonymity, said that a note found at the scene addressed to Ms. Spade’s 13-year-old daughter indicated that what had happened was not the child’s fault.

FAIR has criticized the Times’ questionable use of anonymous sources. One of the paper’s internal rules, not followed here, is that anonymous quotations should be accompanied by an explanation of why the source needed to be anonymous. In this case, it’s likely that the unstated reason for requesting anonymity is that the sharing of a suicide note with the press is an unethical violation of a dead person and a grieving family’s privacy.

Furthermore, reporters are encouraged not to suggest a suicide was “caused” by a single event, such as a job loss or divorce, as research shows no one takes their own life for one single reason, but rather when outside stressors and health problems converge. “Reporting a ‘cause’ leaves the public with an overly simplistic and misleading understanding of suicide,” the ASFP states.

Precisely the kind of coverage the group is warning about appeared on PageSix, where reporter Yaron Steinbuch speculated: “Kate Spade fell into a deep depression days before hanging herself because her husband — who had moved out of their Park Avenue home — sought a divorce, according to a report.” At TMZ it was, “Kate Spade Depressed Because Husband Wanted a Divorce,” while the New York Daily News headlined an article, “Kate Spade’s Suicide Sparked by Husband Seeking Divorce.”

Andy Spade’s statement following his wife’s death addressed false claims the couple was divorced, indicating that they were separated, but never discussed divorce.

The media’s job is to serve the public interest. It has the potential to educate people about otherwise taboo topics through responsible, ethical reporting. But irresponsibility regarding issues of suicide does a great public disservice.

The difference between a careful and careless report could be the difference between life or death, stigma or help-seeking.

If you are in crisis, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 800-273-8255 (TALK), or contact the Crisis Text Line by texting TALK to 741741.

Shares