Most days, I'm not sure where to start saving the world.

We are incessantly pelted with crises — social, economic, humanitarian, environmental. And for those of us trying to be useful and good, it feels overwhelming, sometimes to the point of incapacitating. Those feelings can be exacerbated when we're trying to figure out how best to approach issues that affect groups outside of our own experience. How can we be effective allies, without becoming defensive or diverting attention? What actions bring about real change, because arguing on social media only achieves so much?

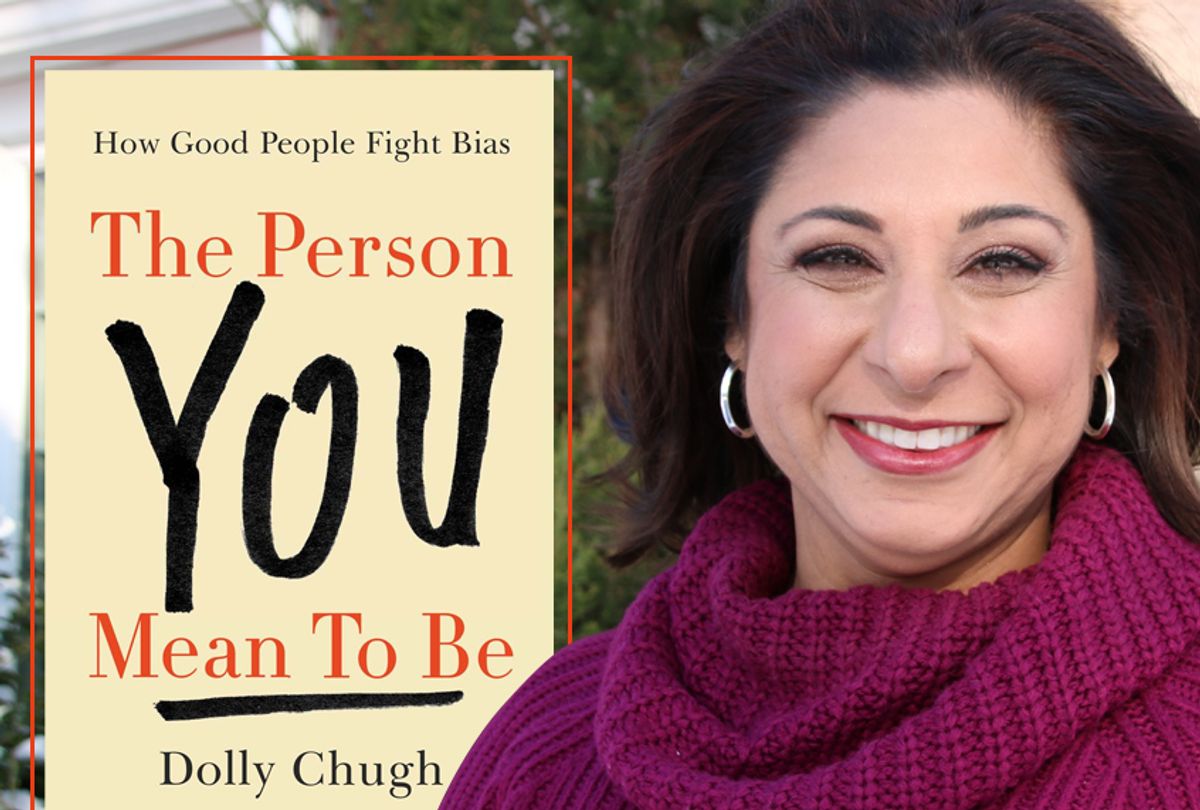

Social psychologist Dolly Chugh has some ideas. In her new book "The Person You Mean to Be: How Good People Fight Bias," Chugh gives us permission to acknowledge our own moral shortcomings, and offers concrete strategies for deploying whatever "ordinary privilege" we may have in our communities. Social progress means accepting our limitations while using what Chugh describes as our "light and heat" — moving with engagement and awareness, and accepting you can't change everybody.

It's a book filled with compassion, but also challenge, one that understands that we're all trying the best we can, but we also have to step up our game. I spoke to Chugh recently via phone about why being "good-ish" is often pretty great.

It starts with forgetting about getting the prize for being the World's Greatest Ally.

"Making the effort doesn't mean you'll always be acknowledged and appreciated for it," she said. "You're making the effort because that's what you care about. The way to that is not by living in a dreamy world of being a good person and just believing that is good enough. We do it, because we actively engage in the work."

And at a moment when many marginalized groups feel the need to be especially wary and protective, public discourse about inequities in power can make those in more dominant groups — hello, straight white men! — feel attacked. All of us, at some point, will be stereotyped in some way. It's just that for some of us, it's a newer experience.

Another temptation when trying to be useful can be to engage in performative wokeness, to deflect criticism with appropriation and self-congratulation. It's why the word "ally" often triggers alarm bells in certain communities.

"That's where Carol Dweck's research on growth versus fixed mindset is key, because I think the ego is very salient in the fixed mindset," she said. "We're works in progress."

And both work and progress require us to admit when we're wrong or when we're learning — to be vulnerable enough to be beginners. Just a few years ago, I wrote a story and casually used the phrase "wheelchair bound." I'd thought nothing of it, because it was a common expression and because I didn't have much direct experience with disability activism. Fortunately, a very generous reader sent me an email explaining why the term was inaccurate and hurtful. That experience didn't just teach me about that one phrase; it made me more thoughtful going forward in how I write about disability issues. That wouldn't have been possible if someone hadn't given me the chance to do better the next time. But it meant becoming comfortable with being called out for being wrong.

"The more times you get called out, the more times you realize the world doesn’t end, and the next time, you get better," Chugh said. "You feel like, 'Oh boy, I’m glad I got called out because I would have kept on doing that — and everybody would be talking about me behind my back."

Chugh has her own versions of these experiences of teachable moments and told me she's learned "by talking about my own mistakes."

"Certainly, some people see me negatively, but I have been surprised at how that level of vulnerability has just opened people up," she said. "It's actually been a great antidote to defensiveness. I feel like maybe there's more power than I realized in taking this on."

READ MORE: The "Sharp Objects" finale and the danger of white womens' tears

And on the other side of the coin, she notes that "one unexpected cost of writing this book is that I have noticed that after people read it, they start texting me every time they do something that they're proud of, like, 'I just watched this show. I just asked this question in a meeting.' On the one hand, the first time it happened it made me feel great because my book is having impact. But then I started to think, 'Wait a minute. I'm supposed to be validating them?' My book made them feel a little vulnerable. They need me to reassure them that I still love them and respect them."

I struggle with these issues in my own life, trying to balance curiosity and a desire to say and do the right things with the fear of making the people in my life the default representatives for their communities. Chugh advises "taking the time to ask multiple people" about the issues that affect different populations to whom you want be of service.

"That way, when you go to someone . . . you can let them know you are going to seek out multiple sources, and you know there isn't one perspective. It's more work; it's more choices that you're going to track down, but I think it's fair."

To make change — starting with ourselves — means recognizing our own blind spots and biases. It also means not always leaping to write off other people for theirs.

"How do we get ourselves out of this really tight corner we put ourselves in, of a big mindset where there’s nowhere to grow, like you either are a good guy or you're not, you either are a racist or you're not?" Chugh asked. "How do we find the little room to grow in there, not because we're trying to let ourselves off easy, but because we're actually trying to hold ourselves to higher standard? The way do that is by growing."

It's exhausting, and there are times when it feels like there are too many burning issues and everybody's too raw and defeated to go on. "None of us can go 24/7 in this effort," Chugh reminds. "We're all going to have to ease back and then ease back in. Giving ourselves room to grow in that is important. It's really tricky." And she advises, "Embrace yourself — there are mistakes coming…. We're going to take some heat, that's okay. Know that not everyone will have compassion for us. That's OK. Keep going."

Shares