When I wrote this editorial, the Senate had merely voted to advance Brett Kavanaugh’s Supreme Court nomination by limiting debate and setting up what was likely to be the final vote regarding his candidacy on Friday. By the time this piece was ready for publication, however, my hunch had been officially confirmed — and now Kavanaugh is on the Supreme Court.

Let’s discuss what this means in terms of Kavanaugh’s ability to make sure that “what goes around comes around” for the Democrats who opposed him along the way.

In terms of Kavanaugh’s future career on America’s most powerful court, that line — which was part of a much longer diatribe in which he cast the sexual misconduct accusations against him as part of a sinister conspiracy involving the Democratic Party, Bill and Hillary Clinton and pretty much anyone upset with Donald Trump’s victory in the 2016 presidential election — has raised a lot of eyebrows. After all, judges are supposed to be impartial and nonpartisan, a fact that Kavanaugh himself has previously recognized and which he reiterated in a semi-apologetic editorial for The Wall Street Journal where he wrote that “a good judge must be an umpire—a neutral and impartial arbiter who favors no political party, litigant or policy.” By seemingly vowing revenge against the Democrats who had hindered his smooth path to the Supreme Court, Kavanaugh made his job appear to be a partisan one when it is very much intended to be the opposite.

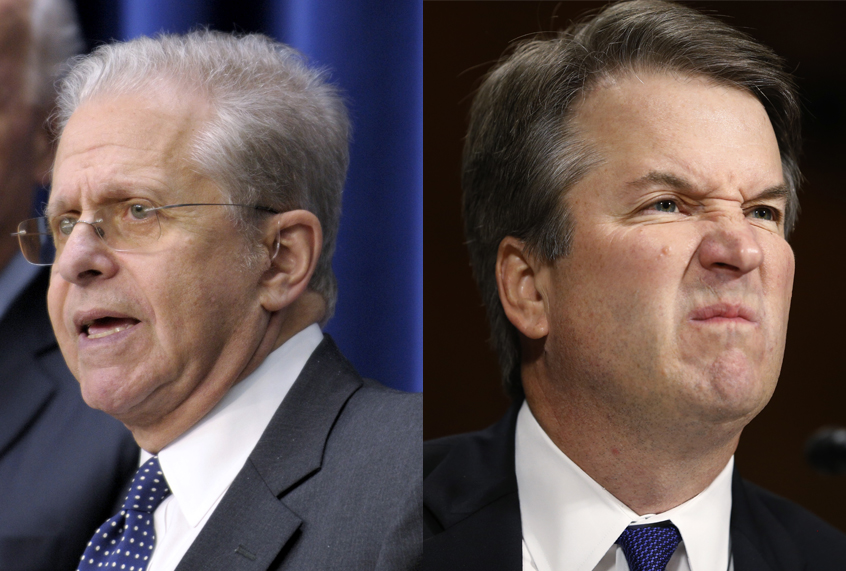

Yet was Kavanaugh actually threatening to change the court into a partisan institution… or was he unintentionally telling the truth, which is that it already is a partisan institution? To find out, Salon spoke with Laurence Tribe, the Carl M. Loeb University Professor at Harvard Law School.

“In a book that I wrote with a colleague named Joshua Matz several years ago called ‘Uncertain Justice: The Roberts Court and the Constitution,’ I explored just how partisan the court was and concluded that really, with relatively few exceptions, it was much more even handed than people gave it credit for being,” Tribe told Salon. “The court certainly lost a lot of its luster after Bush v. Gore, and it has from time to time vindicated the views of those who think of justices as just politicians in robes. But on the other hand, when Chief Justice [John] Roberts cast the decisive vote upholding the Affordable Care Act and a number of other equally notable occasions, the court has given people reason to trust it again.”

That said, Kavanaugh’s confirmation could be the proverbial straw that breaks the camel’s back when it comes to viewing the court as a nonpartisan institution.

“I think it’s used a lot of capital in the interim and I think, now, the likelihood that the court could be a respected institution if Kavanaugh, despite everything we know, were confirmed is pretty low,” Tribe speculated. “I do agree with you that people should get over that myth that the court is wholly apolitical, because it has always been a part of politics. Justices are selected in a political way. But the court has transcended the most extreme versions of partisan politics. Nobody has ever been confirmed on the court with a kind of promise to get back at those who made the road to confirmation difficult. We have in this case, at least one justice who can’t give a fair shake by his own acknowledgment to many of the groups that appear before the court in well over half the cases that are of any real importance.”

Yet the politicization of the Supreme Court which has culminated in the Kavanaugh confirmation hearings had much deeper roots. As Lucas Rodriguez explained in a brilliant piece for Stanford Politics in 2016, the tendency toward politicization can be traced back to a concerted effort by presidents from both parties to root out potential judges who might be independent-minded and make sure that the ones who are appointed can be all-but-guaranteed to support their party’s doctrine.

READ MORE: Beto O’Rourke & Martin O’Malley: the dark horse ticket that could beat Trump in 2020

If we consider the number of cases decided by single vote majorities to be a fair proxy for a Court’s polarization, it becomes easy to see that our current Court is by and large the most partisan in years. In the period between 1801 and 1940, less than 2 percent of all the Supreme Court’s decisions were decided by a 5–4 vote. By contrast, the Rehnquist and Roberts Courts have seen just over 20 percent of their cases be decided by this small margin. This shift provides a clear indication that polarization has indeed spread to the judiciary.

Modern justices seem to often vote in ideological alignment with the party of the President that appointed them. This phenomenon is relatively new. In the past, the party of the appointing President did not predict a justice’s votes. Twentieth century justices Earl Warren, William Brennan, and Harry Blackmun all leaned liberal despite being appointed by Republican Presidents. Now, these types of justices have become extinct. In the 2014–2015 term, virtually every 5–4 decision the Court gave out was split perfectly along party lines. This, combined with the increase in 5–4 decisions, is an indicator of just how partisan the Supreme Court has become.

This increased partisanship has been attributed to a variety of causes, most notably the changing nature of judicial appointments and the types of clerks the Judges hire. As Adam Liptak, a Supreme Court Correspondent for the New York Times explains, the two parties have begun vetting Court candidates years in advance, closely watching their decisions in lower courts to ensure they are in line with the party’s goals. This increased partisanship of Supreme Court nominees is reflected by the most recent confirmation hearings. The 5 most senior judges on the Supreme Court only averaged 3 negative votes against them; however, the 4 newest members received an average of 33 negative votes.

Personally, I would say that the turning point in the Supreme Court’s history was the 5-4 decision it rendered in the 2000 case of Bush v. Gore. While the court would have been attacked for its ruling regardless of whether it had benefited Republican presidential candidate George W. Bush or Democratic presidential candidate Al Gore, it was certainly terrible optics for the five conservative justices to write a decision riddled with internal inconsistencies that blatantly contradicted their own oft-avowed pro-states rights arguments in order to decide the 2000 presidential election for a Republican. Nor does it help that in the 2010 case Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, the conservative majority made it easier for the wealthy to rig elections in favor of their preferred candidates (who, inevitably, lean conservative).

Just to be clear: If it had turned out that a majority of the Supreme Court’s judges were Democrats, the court would be a Democratic institution. As it happens to be, however, the majority on the court are now staunch Republicans, and as a result the Supreme Court has become nothing more than a wing of the Republican Party. This is unquestionably a bad thing for democracy, but perhaps there is a silver lining in the fact that at least the court’s blatant preference for one party over another will now get baked into our political discourse. The disingenuousness of people like Kavanaugh insisting that they aren’t partisan is transparent instead of barely concealed.