“I want to tell you a story… without an ending! Maybe you can supply it!”

— Batman, Vol. 1, #47, June 1948

First, an unmasking: my grandfather was Batman.

It was a well-kept family secret, until now, that when Milton L. Nemetzky was a high school freshman, he moonlit as a Caped Crusader, stealing away between third and fourth period to Locker #539, where he’d twirl the combination, trigger its secret switch, climb into this portal and descend to his sub-basement lair: a boiler room filled with gadgets and vehicles created in collaboration with a kindly old custodian named Burt, his Alfred. Milt would slip into his black union suit, cape, mask, and emerge ready to battle upperclass bullies—Thwack! Boom! Zowee!—making those hallways safer for short Bronx Jews evermore.

This is fiction, of course. The truth is more tragic. And less. I’ve always been nuts about superheroes, but not in the typical trivia-obsessed fanboy sense, so I knew less about comic books than you might expect. My vague understanding was that most of the 1930s creators were Jews using the era’s popular medium to wage fictional proxy battles whereby we Hebrews could confront and wallop the rising tide of Nazism, and reconcile our legacies of immigration and assimilation.

Case in point, Superman’s origin story: the distinctly Hebrew-sounding Kal-El is sent by his parents from dying planet Krypton to be discovered and adopted by kindly Midwestern farmers. It’s basically Moses in the reeds. Or else, a stand-in for the wave of Eastern European Jews fleeing persecution, braving the vast expanse of the Atlantic, aiming for New-World adoption.

The Nemetzkys came from Kherson, a Southern area of what’s now Ukraine, near the Crimean border. Like Kal-El, our family escaped destruction. We eluded the genocidal pogroms of the 1905 Russian Revolution and arrived in America in 1906, enduring the tenement sweatshops of the Lower East Side garment district before moving to the Bronx. My great-grandfather Israel Nemetzky married Pauline Silverman, granddaughter of a well-known Belarusian rabbi. Together they made Milton, born in 1915.

Milt attended DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx, a storied alma mater of countless entertainment luminaries including comic book legends Will Eisner, Stan Lee, and the co-creators of Batman: Bob Kane and Milton “Bill” Finger.

What I didn’t realize until recently was that they graduated the same year, 1933, and Milt was an orphan, just like Bruce Wayne.

Everyone knows Batman as the mortal superhero—the one without mutant/alien/magical powers—but most forget he began as a detective (“DC” stems from “Detective Comics”), inspired by sleuths like Sherlock Holmes. I remember feeling that first investigative rush when I pieced this together. Probably a coincidence. But…what if Grandpa’s childhood tragedy was the inspiration for comic history’s most iconic superhero genesis?

Milt’s origin story: When he was five years old, his little brother Simon died of diphtheria. Two years later his father died of a heart attack. Grandpa Milt always told the story of how he contracted diphtheria the next year, but his father’s spirit visited him on his deathbed, saving his life.

Pauline was a wonderful mother. She wanted Milt to have a father figure, so she remarried in 1927. Legend has it he was a sonuvabitch cheapskate named Hyman Frost (who just sounds like a Batman villain). Frost pushed Milt to change schools because he didn’t want to pay the bus fare. Milt refused. He secretly walked to DeWitt Clinton every morning.

Then, a month before his 14th birthday, Milt’s devoted mother died, the last member of his immediate family gone.

I’ve tried to imagine. He must’ve felt so cursed, so vulnerable. And at the same time, invincible.

He was The Survivor.

I needed to understand more about him, about his origins, so I did some digging. And the problem with doing internet detective work, I learned, is that sometimes you find what you’re looking for.

The New York Times, Daily News and Brooklyn Daily Eagle articles were rough to read, their headlines seemingly ripped from the pages of comic book villainy: “Midnight Walk in Bronx Costs Woman’s Life—Seek Fiend as Slayer.” “Find Bronx Woman Mortally Beaten.” “Police Seek Panic Stricken Hit-and-Run Motorist and Fiend in Woman’s Mysterious Ash Pile Death.”

Details are sketchy, accounts conflicting. The basic story: on her way home from a late-night meeting of her Jewish charity organization, Pauline Silverman Frost disappeared. She was found by workmen in an abandoned lot the following morning, her skull fractured, her clothes torn. Alive but unconscious, she was brought to Lincoln Hospital and died six hours later, on June 4, 1929.

I remember staring at a particularly striking photo in the Daily News. It’s my great-grandmother in a hospital bed, eyes closed, face unmarked and beatific. A nurse sits vigil, in profile, one hand lovingly cupping Pauline’s forehead while the other holds open a small book, maybe a Bible. It’s beautiful and horrifying.

Pauline was either intentionally attacked or accidentally struck by a car and left for dead. The articles speak of “squads of detectives…[doing] a double hunt for a fiend and for a hit-and-run driver.” They offer detailed maps and images, the kind that would never be made public today. “Mrs. Frost was respected and loved by her neighbors,” they say. “Her last acts on earth were concerned with charity.” They mention Pauline’s surviving son, yet misspell his name as Netetzky or Menepzky, a final cruel insult.

I shut my laptop, scared to learn more. The shadowy outline of her murderer, The Fiend, haunts me, even some 90 years later. How badly must he have haunted that poor 14-year-old orphan? Knowing he was still out there, still free, still alive? What if I could track him down?

But the trail ended. How could it be such big news for two days, I wondered, and then…nothing? With the case now ice cold, what would be gained if I somehow found this long-dead Fiend? Would I confront his ancestors during family dinner, divulge the truth of their bastard forebear? For that matter, what was I trying to gain in looking for a link between Milt and Batman, aside from some ego-stroking coattail-ride? The simple truth was: these were mysteries unsolved. I was in it now. I craved answers, justice, revenge. I thought of Bruce Wayne. . .

Batman’s origin story, as first presented in a single nine-panel page of Detective Comics #27 (Nov 1939) and rehashed in every Batman iteration since: Bruce Wayne is born in 1915 (like Milt) and lives “a happy and privileged existence” until his parents are gunned down by a small-time criminal while walking home from a movie theater. Young Bruce takes an oath—“And I swear by the spirits of my parents to avenge their deaths by spending the rest of my life warring on all criminals”—then becomes a master scientist and well-trained athlete of “physical perfection,” before adopting his timeless disguise: “And thus is born this weird figure of the dark…this avenger of evil. The Batman.”

I considered the vengeance that spurred Bruce’s oath against all criminals. The only time I’ve felt a desire for such broad retribution was after those Nazis invaded Charlottesville, spreading hate throughout our town, eventually striking an innocent woman with an automobile and leaving her for dead.

I interviewed my father and my aunt, asked them if Milt ever sought justice, and they told me Grandpa searched for answers back in the pre-internet 1970s, visiting libraries to scour microfiche.

“Did he ever seek vengeance, though?” I asked.

“That wasn’t his way,” they said.

This was Milton Nemetzky:

Pauline was killed in June, and to shield Milt from grisly newspaper headlines while he sorted out the details, Hyman Frost shipped him off to Boy Scout camp at the last minute. Exiting the bus that first day, Milt wore a borrowed uniform, way too big. As the scout master called roll and shuttled boys into their various troops, Milt was the only kid not on the roster.

“What’s your name?” the Scout Master asked. “We don’t know who you are.”

I can picture all those boys in their respective groups. Yet there stood Milt, alone in an ill-fitting costume. An assistant finally explained to the scout master that this was the boy whose mother had been killed, and they found a spot for him. According to my aunt, Grandpa swore an oath then and there—”They don’t know who I am now,” he said. “But dammit they’ll know who I am by the time I leave.”

Even then, he was the kind of guy who found a way to make a name for himself–through excellence. Milt was an athlete, hardworking, handsome, kind, and all of this made him known.

When he returned from camp, he left his step-father’s house, a block away from where Bob Kane lived in the East Bronx. He was taken in by his aunt and uncle on Briggs Avenue, just a block away from Milton “Bill” Finger’s place on Grand Concourse (they’d remain neighbors for the next decade).

By all accounts, Milt was the Cinderella of this new household, an afterthought compared to the two adored older boys. He played violin at the school talent show, just months after his mom was killed, and brought the house down with a tear-jerking rendition of “Thais: Meditation” (Bob Kane also played violin). By the time he graduated, Milt was known as “Nemo,” a combo of his last name and the memo pad always sticking out of his back pocket.

This isn’t a story about how Milt became a billionaire playboy philanthropist, but like Bruce Wayne, Milt devoted himself to physical training. He graduated from NYU with a degree in education and became a phys ed teacher. He took pride in his body and was fastidious with his wardrobe. Among other things, these physical traits must have attracted my grandmother, whom he married in 1938, and though I often heard her poke fun at his attention to costuming, she truly appreciated the tasteful, handsome man he was.

“Milty!” she’d jab. “What’re you getting all dressed up for, just to sit around the house on Sunday?” Maybe he recalled that first day at Boy Scout camp, wearing that ill-fitting uniform. Maybe this was a small, sartorial manifestation of his vendetta against that moment.

In general, though, Milt went on with his life. I imagine the heartbreak was always there below the surface, but he moved forward.

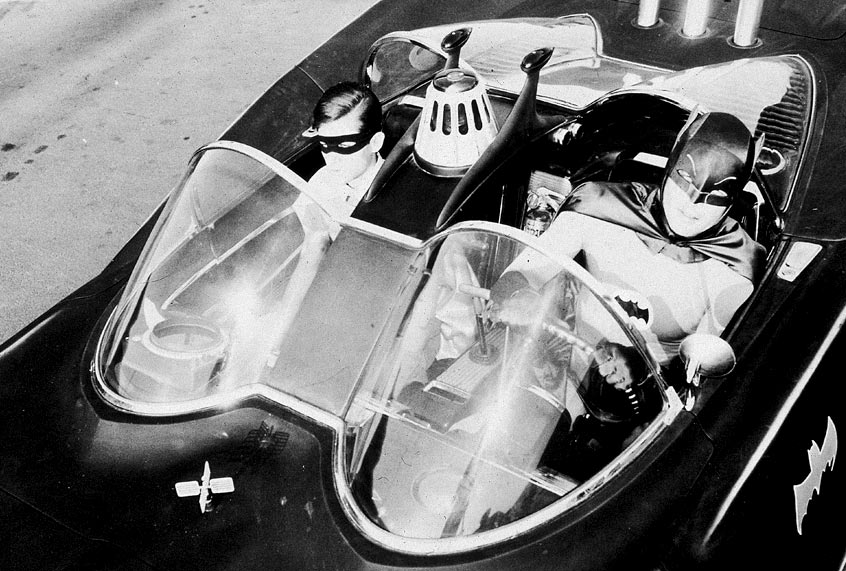

Contrast this to Batman, the superhero that novelist Austin Grossman called, “the costumed patron of the walking wounded, of simply Not Getting Over It.” Even the most juvenile Batman iteration pokes fun at Bruce Wayne’s lack of psychological growth. In “The LEGO Batman Movie” (2017), Alfred spots Batman staring at a portrait of his parents.

“I’m a little concerned,” Alfred says. “I’ve seen you go through similar phases in 2016 and 2012 and 2008 and 2005 and 1997 and 1995 and 1992 and 1989 and that weird one in 1966.” It’s one of those self-referential jokes about all those brooding Batman films, intended for adults, but it speaks to the problem at the heart of some origin stories: that a single travesty must haunt and define us, forever. “Don’t you think it’s time you finally faced your biggest fear?” Alfred continues. “Being part of a family again?”

These 1989-2017 movies all depict Batman in his crime-fighting heyday. You have to turn to graphic novels to see how this psychosis matures. Frank Miller’s “The Dark Knight Returns” depicts an aged, bloated, broken Bruce Wayne, lonely and perennially tormented not only by the murder he witnessed as a child but by the countless others he’s countersigned since. Todd Philips’ forthcoming “Joker” movie, scheduled for release in October 2019, promises the supervillain’s origin story, likely offering justification for whatever brutal twist created the Clown Prince of Crime. As a Batman fan, I’m gonna see the movie—but part of me wants to say fuck that, we don’t need to glorify and validate his evil.

I don’t mean to make light of the pain and trauma and abuse and mental illness that plagues Batman and his villains. These are serious, nuanced issues, and I truly have no expertise or personal frame of reference from which to speak. But life is rarely bereft of trauma, and guidance can be found from a hero like Milt Nemetzky rather than the Dark Knight or the Joker.

I also don’t mean to imply that Milt’s fortitude was entirely inborn. While he was a second-class citizen in his new home, his Uncle Jack and Aunt Tilly — who lived nearby and never had kids — showered him with affection and adopted him as their own. “I never felt lonely or unloved,” he’d say. “That’s how I made it through.”

And so, this is a superpower worth cultivating: it’s not “finding the silver lining,” or “turning the other cheek” or “sucking it up,” and it’s certainly not about eschewing justice. Hard work and perseverance are crucial. But there’s an important difference between justice—righting a wrong that can create positive change in our world today—versus vengeance—an ego-driven wish for violence, retribution, and subjugation of a broad, faceless Other.

Yesterday, my kids and I were in the costume store, getting ready for Halloween, and they saw a Donald Trump mask. They asked if that was President Business from “The LEGO Movie.”

“No,” I said, “but that is our current real president.”

“Is he a good guy or a bad guy?” they asked.

I knew they were thinking of the Will Ferrell character, who starts bad but becomes good over the course of the film, so I said something about how all people have a little good and a little bad in them; how sometimes people start bad and become good. Of course, I wanted to say: “Son, that man not merely a bad guy, but one of the worst men our species has ever produced. He had every privilege, every opportunity to do good, and he chose evil.”

We have the opportunity to make this choice, every day.

Maybe Grandpa Milt was really Batman. He graduated the same year from the same school as Kane and Finger, had the same name, played the same instrument, lived a block away in both their neighborhoods, and experienced a well-publicized tragedy that left him orphaned. Maybe he inspired them. Or maybe it’s sheer coincidence. I was searching for a link, some incontrovertible evidence of their connection: the two Miltons standing side by side in a yearbook photo, each flashing the same secret hand signal, like real BFFs. I haven’t found it, yet.

For all I know, Grandpa’s job as a phys ed teacher was a mild-mannered cover for his secret life as a vigilante. For all I know, Nemo the Survivor tracked down The Fiend decades ago, visited savage vengeance upon him. But probably not.

More likely, he dealt with the heartbreak but toughed his way through it, charged forward, created a life worth living, found peace.

Sometimes, happiness is the best revenge.