“He loves me. Of course I’m not in an abusive relationship. I’m a strong, capable woman.”

I repeat these commandments while looking for my husband’s car in the train station parking lot. In a roar of announcement, he pulls in and warmth floods my body: joy at his arrival laced with something I’ve avoided naming.

“Hey, baby.” He kisses me.

“How was work?” I ask.

“Bar was packed. We actually made some money tonight.”

“That’s wonderful.” I shape my words delicately. Not too earnest, not too casual. Unless I’m careful, he’ll spin my sincerity into sarcasm, or hear casual as lacking affection.

“Why are you wearing so much make-up?” He frowns. “You’re supposed to be a feminist.”

“Wha–,” I catch myself. “I’m sorry. I had an audition.”

He opens the glove compartment, grabs take-out napkins, wipes my lips, cheeks, eyes. Like a sunflower turning towards the burning sun, I lean into him, complicit in my erasure.

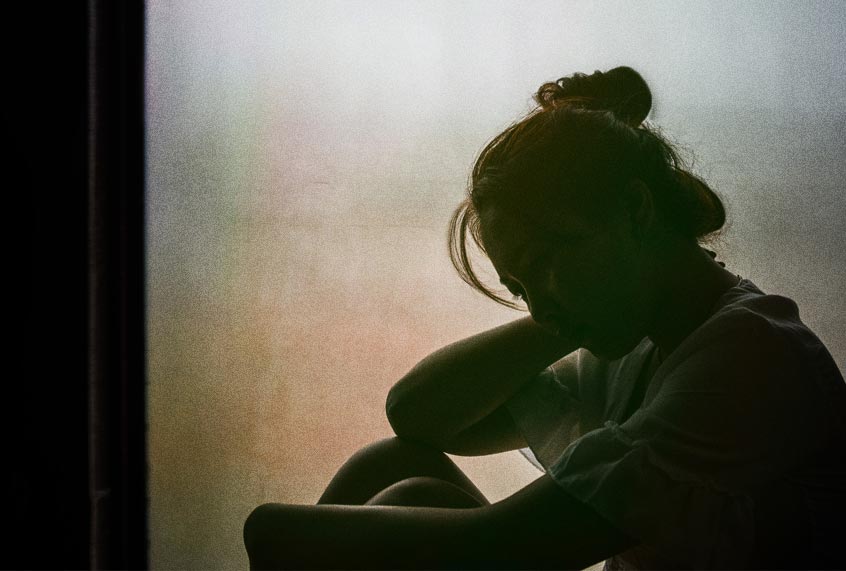

Abuse always begins small, which is why it’s so easily ignored and rationalized. Until one day, you find yourself in full-blown pain, oppressiveness, and absurdity.

My phone buzzes with a text from my mother. “Remember, he needs your patience and strength. That’s why you’re perfect for each other. Love is forgiveness.”

I stare at the phone and hide it. I haven’t told her the full truth about my American husband, 11 years older than me, a charismatic “feminist man raised by a feminist mother” whom I married a year and half ago. Born and raised in California, the quintessential golden surfer god, he embodies every male quality I grew up idolizing: handsome, funny, kind, romantic, sensitive, tall. When we first met, although I had promised myself I “wasn’t dating,” his dogged pursuit and dazzling charm ultimately disarmed me.

I’m loyal to my husband for the same reason I’ll always love my father. Despite my growing shock in trying to navigate a husband prone to similar outbursts, I’m convinced that if I discover the magical combination of words, he will feel better, be kinder. So I play it “cool” as most millennial women have been taught. From the time my husband and I began dating, I’ve laughed away and shrugged aside his passive aggression, overt aggression, affection followed by coldness, passion followed by ghosting, and now, the other women he flirts with at the bar where he works. He brings home their names and numbers on crumpled receipts, which he proudly displays like a peacock fanning its tail. But I was a Women’s Studies major, I remind myself. I’m strong, calm, mature, and I won’t give up on my marriage over a rough patch.

Besides, he doesn’t hit me. He’s just having a hard time at work, I tell myself, and sometimes, the frustration bleeds into our marriage. Furthermore, my ambition and career often require long hours and faraway travel, taking me away from him. Out of love, he says, he grows angry, imploring I work closer to home, spend more time with him, or he’ll “find someone else.” In addition to disliking my wearing makeup, he hates how often I go to the gym, buys me bulky sweater dresses to “cover (me) up from judging eyes” and regularly insists I speak less assertively because “It’s presumptuous to think everyone wants to hear your opinions.” My husband calls his adamant policing of my choices, location, body and voice “loving protectiveness”—for my own good, the sake of our marriage, in the name of decency and values.

I spend my days racing from auditions to meetings, trying to prove my worth, constantly scrutinized, directed, adjusted, and rejected by others, only to come home to more.

“What you thinkin’ about?” he asks as we drive home.

I look at him, the distance between us thick with the scent of something dying. “Just something I was writing on the train. About love.”

A pause.

He meets my eyes. “You know, all I want is the best for you, baby. For you to be happy. Because I love you.”

“Thank you. Me too.”

I’ve come to realize that our relationship “works” because I excel at belonging to him. Deferring to his ego and temper, calming his jarring moods using words, sex, distraction, humor and food, extinguishing fires he lights with his family, friends, bosses. I don’t merely walk on glass; I dance so delicately on glass that the tinkling song of my toes upon shards sounds lovely to all witnessing ears.

Dancing upon glass is the emotional labor of the peacekeeping—and ultimate enabling—in an abusive relationship. Failing to dance beautifully promises dangerous results. On days I say something that annoys him, or if he’s in a grim state of mind, he brings up my green card, procured through marriage, reminding me that my being allowed to live and work in the United States is dependent on him. Whenever he “needs space,” I’m banished from the house like a misbehaving pest. All his actions hinge on a lust for dominance. All my efforts are for his care, while my needs are starved.

The real nightmare though, is I know all this.

I studied partner abuse in college, so intellectually I’m acutely aware of the precarious situation I’m in, and how quickly and gravely it may escalate. I float the idea of marriage counseling, but he refuses. Instead, I scour books and articles to sneak therapy into our marriage, in an effort to raise his self-esteem. Emotionally violent partners are governed by insecurity, hence my husband’s talent for weaponizing incoming information as an ambush against him, an affront to his masculinity, or a reason to attack me. This, I can see, is why he loathes the very qualities he once loved: my youth, physical beauty, work ethic, intelligence—traits that threaten his spotlight in the “pack.” Which then leads to an obsession with control and permission, demanding he authorize every social invitation and financial decision, while criticizing my dreams of writing as being “too farfetched.” Nothing endangers a bully more than another person’s audacity to dream—our dreams are sacred ground that no other person can completely dictate.

I can trace this narrative. The haunting query isn’t “How am I here?” but “Why am I still here?”

“I love you so much,” he says suddenly. “No one understands or loves me the way you do. I’d die if you left.”

These sentences materialize whenever he senses—or I directly express—my pain, giving me, as Leslie Morgan Steiner says, “the illusion of control”; two other telltale signs of toxicity. Intimacy has curdled into our own Stockholm Syndrome.

“I love you, too.”

We arrive home, tucked deep upstate New York, so removed from civilization that we don’t have cell reception. I enter, struck by other classic abuse signals: isolation, economic desperation. My wallet carries only my green card, with my weekly earnings surrendered to our bills. He requires so much emotional energy that I’ve lost contact with all friends and most family. Even if I wanted to leave, I’m legally, financially, socially, geographically ensnared by a noose woven partly by my hands.

There is also the element that continues to puzzle me — even if I had resources to leave, I’m strangely roped to him.

He loves me. Of course I’m not in an abusive relationship. I’m a strong, capable woman, I tell myself. He’s just a riddle I have to solve.

This is our trap.

Millennial women are steeped in the pressure of being the perfect blend of high-achieving, feminist wunderkind and sweet, nurturing caregiver. Unless we’re careful, our mantra “be strong, be compassionate, be cool” metastasizes as an all-consuming expectation to be both invulnerable and amenable to pain; to be fun and confident, but also deferential; to love, forgive, and remain loyal to the point of wounding ourselves.

Shame keeps me from confessing the full truth to my mother or any other person. Shame that while everyone else is succeeding in life and love, I, a supposedly intelligent, capable woman, have utterly failed.

Largely why millennial women remain committed to toxic relationships is because we don’t identify with the timid, battered housewife trope, and our relationship with success and failure is almighty. The American Psychological Association has documented women’s steady rise in perfectionism and pressure to succeed, associated with unprecedented levels of clinical depression, anorexia, self-harm and punishment, and workaholism. Compounded with other conditioning, has this rise attributed to a perilous tolerance for emotional abuse?

The love we expect, accept, create, ask for, and are given—regardless our feminism, intelligence, or work ethic—often has nothing to do with strength, persistence, worthiness, or failure and everything to do with toxic power. According to the National Domestic Violence Hotline, 49% of women in the United States have experienced psychological abuse from an intimate partner in their lifetime, and the majority of survivors are between 18 to 35 years old. However, the statistics reflect solely the cases reported. The covert nature of emotional harm increases its likelihood of being silenced, hidden, unreported, and continued.

I look at him. He once loved every bit of me, and it’s the memory of this love that makes leaving excruciating. Daily I think of the vivid past, the hypothetical future, scolding myself: If I were enough, worked hard enough, he might love me like he once did.

Living on a “what if” is like being in love with a closed casket. My efforts alone won’t mend our marriage, or secure another’s wellbeing. No person can do the work of two people—neither the personal work nor the emotional labor—to sustain or save a relationship. I created my marriage in extension of my parents’: with them, with him, the riddle “How can I help you, heal you, make you happy?” can never be answered for it has no answer.

Authentic love, like true feminism, is about equality, and should never feel punishing. An emotionally abusive relationship is not our duty, failure, or sphinx to conquer. Looking at my husband, other faces appear. Ex-boyfriends who repeatedly ignored my value, squandered my love, while I let them. Ultimately, betraying myself.

The deepest betrayal is the one we commit against ourselves. If I am culpable of disempowering decisions, I have equal capability to conspire in my empowerment. Thus, coming into focus, a final face: the woman I could be, should I make new choices.

After the choice of person we decide to be, our choice in partner is the most impactful decision in our quality of life. Think of all the conversations you’ll have or won’t. Books, movies, museums, places you’ll explore or won’t. Children you’ll raise or miss, laughter you’ll share or lose, careers, talents, legacy you’ll fruit or destroy, love, tenderness, accountability you’ll receive or be denied based on the partner you choose. Every bit will whither or nourish, waste or enhance our time on this planet.

I take a long, honest look at my husband, and myself. Remaining his wife will mean a smaller life. A life shrunken by compromises with my potential, goals, and personality to fit into the girl he requires. Who could I be, what trajectory could I ignite were I to redirect the energy invested in his needs, career, caretaking, wellbeing, and family, into myself? To grow to my fullest wingspan, rise into skies unknown, I have to divorce him.

It turns out the qualities my ex-husband and ex-boyfriends thought made me their “perfect match”—my ability to read people, my acuity for thoughtful observation, critical analysis, steadfast grit, resourcefulness, and discipline—are the ideal talents for a life in writing, publishing, and public speaking.

If silence, confusion, gaslighting, and fear act as shackles, our voice is our freedom. The voice is a muscle. The more we use it, the stronger it grows. The first “No” is the hardest. The first time we utter No, the word will feel like a small, cold pebble perched on the tongue, begging to be spat out. Once we let that first No soar, each consecutive No, each sentence made in declaration of our truth becomes easier to voice. We articulate our rights and own our power for we weren’t born to solve riddles.

We were born to write anthems.