This is purely based on a gut feeling, but I'd bet Netflix's "Sex Education" is not a popular or significant conversation starter in West Bend, Wisconsin. Or maybe it is. Either way, hopefully some of its residents are watching the show.

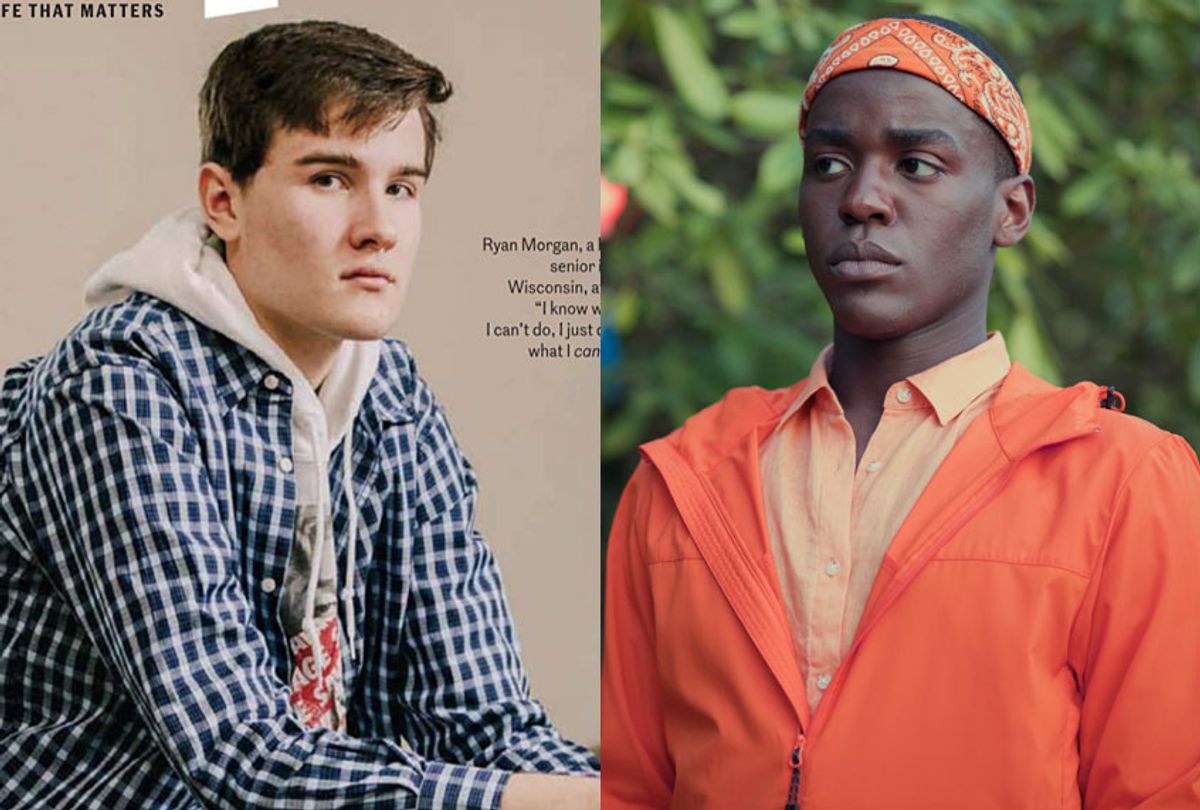

West Bend, a town of just over 30,000, is the setting for the widely discussed and pilloried Esquire article "The Life of an American Boy at 17," the first of the magazine's series on Growing Up in America Today released on Tuesday.

The titular boy is Ryan Young, a tall kid of divorced parents who plans to work at the local utility plant when he grows up. Ryan hunts with his dad and enjoys spending time with his girlfriend Kaitlyn who "loves to watch the sunrays burst on tree branches after an ice storm."

At the top of the story, Ryan contends with the memory of having smacked a female classmate in the face after she slapped him. For his role in the incident, which happened a year prior to the interview, Ryan received a couple of hours in the school suspension room and a ticket referring him to the local municipal court. He pleaded not guilty.

"Ryan thinks that if he were a girl, he wouldn't have been punished," reports the article's writer Jennifer Percy. Following a surfeit of description about Ryan's typical day-to-day life, Percy and her subject return to the altercation. "He has this idea that since I'm a woman, if I were in the same situation, I could do whatever I wanted," she observes. "I could pull out a knife and stab a guy, and I wouldn't get in trouble. He leans forward and clasps his hands. 'Well, I don't know. I still don't really understand it. I know what I can't do, I just don't know what I can do.'"

The way Percy writes of the incident, it doesn't fundamentally alter the trajectory of Ryan's life, mind you. It's simply on his mind, something that nags at him. In "Sex Education" a character named Eric, played by Ncuti Gatwa, punches another classmate in an act of misplaced rage resulting from a homophobic attack he hides from his father.

This attack changes Eric in a crucial way, initially threatening the bond he has with his lifelong best friend Otis (Asa Butterfield) but eventually leading him to realize that the world will inevitably view and treat him in certain ways, sometimes based on long held assumptions that have nothing to do with who he is as an individual.

And Eric's father loves him, even though he initially struggles to express his concerns and fears for his child. But patiently and lovingly takes the ride into the unknown with his son, very much like Ryan's father does.

Eric is a fictional figure and, well, British. But among the many reasons the series feels so honest and heartfelt is that we know these characters not only from teen movies but from our own lives. Ryan Young exists, truly, but so do plenty of Erics.

Eric, Otis, their parents and classmates are the creations of a woman, playwright Laurie Nunn, and the adventures they experiences together and separately through season 1 of "Sex Education" were written mostly by women. "I didn't set out to talk about modern masculinity in particular, but I've always been interested in exploring male vulnerability in my writing," Nunn said in an interview with Salon conducted via email.

She goes on to add, "At its core, the show is about communication. And many men still struggle with openness and vulnerability, so this was something I wanted to explore and challenge through the male characters of the show."

"Sex Education" is set in a British high school, which therefore dictates that it would feature what Nunn calls "certain stock male characters": the bully, the jock, the nerdy invisible kid, the gay best friend. But the most popular kid in school isn't mean or a narcissist, and even the bully is treated with a careful tenderness that allows him room for redemption. This is also true of the adults in the series, who range from the strict principle Mr. Groff — the bully's father — to the goofy science teacher who struggles to relate to his kids.

"I wanted to write a wide range of male characters," Nunn explained, "some who are still finding communication difficult, like Mr. Groff, and others who are more evolved and in touch with themselves, like Otis, Eric and Jakob," the father of Otis' love interest.

Nunn said she wanted the central through-line of "Sex Education" to be what she describes as a love story between two male best friends. But another key thrust of the series revolves around Otis and his developing friendship with Maeve (Emma Mackey), the secretly-brilliant school outcast who recognizes Otis' aptitude with counseling his peers on sex and relationship issues. Otis' talent is the result of being raised by a mother who is a sex therapist (played by Gillian Anderson) whose frank, cold and didactic approach to sex creates in Otis a blizzard of internalized conflicts as well as a surplus of empathy.

But as much as Nunn and the series' writers present the various plot threads in "Sex Education" to prioritize the nuances of female sexual identity and how that connects to each woman's agency, the series' thoughtful depiction of the varied challenges inherent to being a man, and the weight and expectations placed on men with regard to masculinity, is appreciable.

"In the writers room we talked about fathers and sons a lot. Themes about older men struggling with vulnerability emerged from those discussions, which led to looking at how those men parent their sons," Nunn said. "Mr. Groff and Eric's father are two sides of the same coin. Both are struggling with their own deeply held ideology of what it means to be a man, but they deal with it in very different ways. Mr. Groff is an unmovable object, whereas Eric's father is willing to grow and learn with his son."

And in this sense, the series intelligently contributes to conversations about how boys see the world, and how well men are raising their boys and girls to navigate the world, in an approachable way that written accounts such as the Esquire story can't quite achieve.

Mind you, these issues aren't the main reason Esquire's account of The Many Struggles of Ryan Young evoked contempt, nor was anything the subject said the cause of it. The magazine series will feature the perspectives of black, LGBTQ and female subjects. But for whatever reason editor in chief Jay Fielden decided to kick off his series with the profile a white male growing up in a 95 percent white town.

This, in the middle of Black History Month.

Not just any Black History Month, mind you, but one that began with the emergence of old photos of Virginia governor wearing blackface and has marked by fresh misdemeanor reported almost every day since. (The headlines could be stacked into a nifty adaptation of "The Twelve Days Christmas":" On the twelfth day of Black History Month, racism gave to me/Ka-a-ty Pe-e-rry's sho-o-o-o-oes!")

But aside from the unfortunate and highly avoidable timing Ryan's profile — designed, Fielden says, to be a look at our divided country through the eyes of one kid — contributes to a larger conversation about masculinity that has at times grown acidic in its dismissiveness.

That vexing and ongoing "toxic masculinity" debate was stirred to seething by the now-famous Gillette ad urging men to question their acceptance of harassment, gender discrimination and bullying.

That ad, by the way, was directed by a woman, Kim Gehrig, which is a major reason many people who decried the ad took umbrage at it. But "The Life of an American Boy at 17" is written by a woman, part of the reason its bone-straight presentation and the philosophical inquiries, stated and implied, work.

And according to Nunn, the gender makeup of the writers' room contributed to the care with which "Sex Education" treats its masculine characters "Because the show is written mostly by female writers, themes of toxic masculinity were brought to the surface organically," she said. "It's something women are talking about a lot at this moment in time. I think the male characters in the show are often struggling with feelings of inadequacy and loss of control, whereas the female characters are searching for satisfying emotional experiences and learning the language to ask for what they want."

With regard to "The Life of an American Boy at 17," it's not the teenager's judgment that should be questioned but that of the adult male whose saw no issues in leading off with his story, in a socially divisive climate where one of the primary complaints is that the Ryan Youngs and Jay Fieldens of the world always receive first consideration.

But wouldn't it have been interesting if instead of debuting the series with that 17-year-old boy, we were given the chance to tag along with a 17-year-old like Eric — a black gay teenager who is just beginning to fully embrace his sexual identity as well as his individuality?

Perhaps Esquire has a subject fitting that profile in the hopper for an upcoming issue, which I look forward to reading. In the meantime it's comforting to know the kind and comforting lessons of "Sex Education" are available for now, in the form of eight nimble, heartfelt episodes on Netflix.

A recently announced second season pick-up means we'll eventually get more, and that's the good thing — one suspects this conversation will still be needed whenever those new chapters emerge. Let's hope they're watching in West Bend and, more importantly, in the Esquire offices. We can all use a brush up on the subject, along with a laugh.

Shares