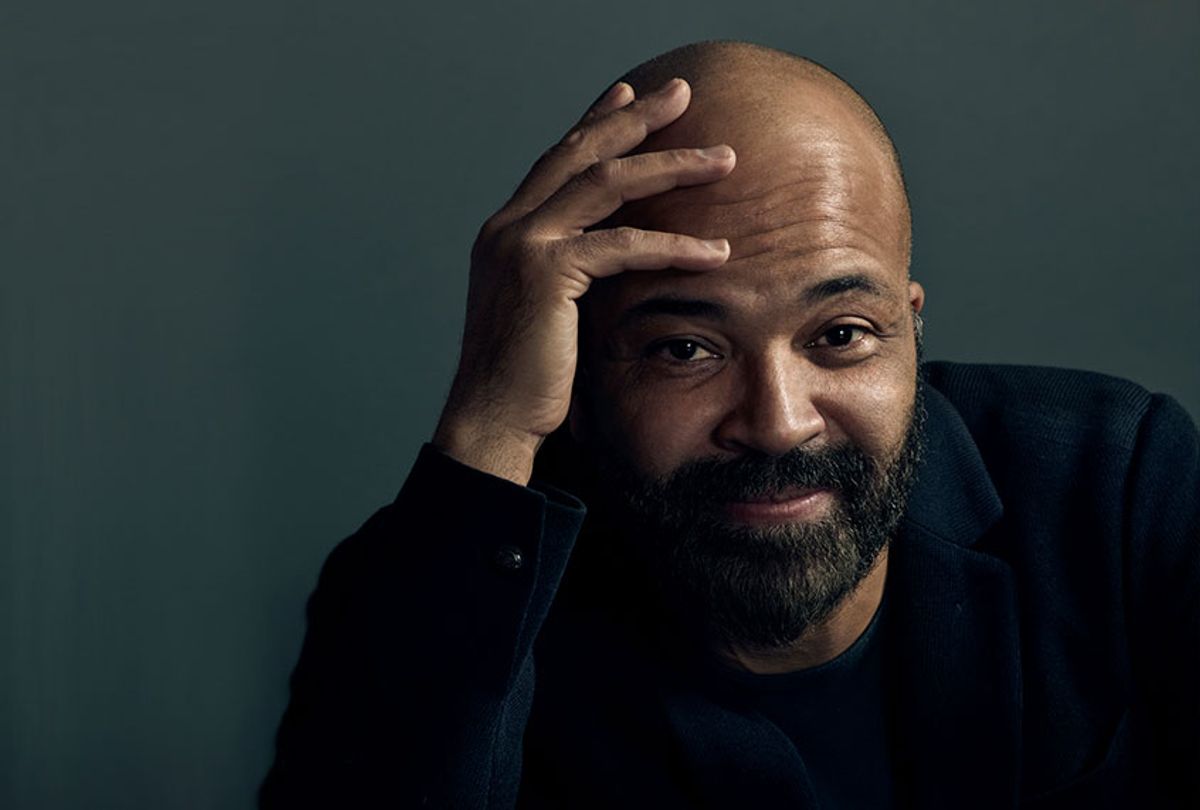

Jeffrey Wright is keen on contributing to a better narrative. For viewers who primarily know of him through his “Westworld” character Bernard Lowe, that makes sense. Bernard may be the most human of the hosts in “Westworld” despite his discovery about what he’s actually made of.

In the real world, Wright is driven by a sense of righting some of the wrongs to which he bears witness in the world, reflecting this in his work, going the way back to his Emmy-award winning performance in “Angels in America.”

Last year he produced the 2018 documentary “We Are Not Done Yet,” a profile of veterans and active-duty service members participating in a United Service Organizations writing workshop as part of trauma therapy, which culminated in a theatrical piece that was filmed and aired on HBO. He visited "Salon Talks" to discuss the film with Salon's D. Watkins.

His new HBO film “O.G.” is a scripted work that took Wright into Pendleton Correctional Facility, a maximum-security prison in Indiana, to portray Louis, an inmate serving 24 years for committing a terrible crime, and who is weeks away from being released on parole for good behavior.

Standing on the verge of freedom, Louis is presented with a risk-reward conundrum in the guise of a new inmate, Beecher (Theothus Carter), whom he recognizes has the potential to use his time wisely or be swallowed by the most corrupt elements of the prison’s social web. In helping Beecher, Louis endangers his own change at a fresh start, one even he isn’t sure about.

In a phone conversation about “O.G.” Wright explained, “it’s not meant to celebrate the incarcerated or to celebrate even the men that I worked with on this film who are incarcerated. To do that is an insult to the injury that they caused, to the harm that they did to others. And that's not our intent.

“Our intent is to add something to the conversation by exploring who they are so that we can ideally help prevent type of damage that they inflicted from happening again," he continued. "And that we can do this not only in service of them, but also in service of their victims. I just want to make sure that's clear."

The moving, contemplative “O.G.” embraces the notion of restorative justice at a psychological level through Louis, who grapples with a roiling stew of emotions surrounding his release, not the least of which are his doubts over whether he’ll be able to make it in the world after nearly a decade and a half behind bars.

Through Wright, who pours a boundless pathos and contemplative tension into his portrayal, we sense Louis’ stoic anguish over his past mistakes and what lies in store for him.

“O.G.,” produced and directed by Madeleine Sackler, is remarkable for its palpable sense of realism. That’s likely because it was filmed over a five-week period in an active maximum-security prison, with a cast of consisting mostly of inmates — including Wright’s co-star Carter. Wright brings a masterful certainty to his work, as does the film’s other main co-star, William Fichtner.

But Carter matches him in every scene, likely because he is living his part.

At no time, however, does “O.G.” seek to minimize the ramifications of the crimes these men have committed or make excuses for them.

This also comes through in “It’s a Hard Truth Ain’t It,” the supplementary documentary Sackler co-directed with 13 of the inmates who participated in the scripted film’s projection, also currently airing on HBO and available to stream as part of its on demand services.

“We should be an informative film,” one of the men says in “It’s a Hard Truth,” saying he and his cohorts aren’t shying away from the truth of what they did but instead seek to tell the stories of how they got there as a lesson to others. In using animated segments to lend visuals to their recollections of vital childhood memories, it ends up being much more than another cautionary tale.

In both films the sense of restorative justice, in which the inmate takes responsibility for their crimes as a part of his rehabilitation, seamlessly integrates into the plot. None of those moments, particularly in “O.G.” are resolved with any certainty or closure.

This fits with Wright’s objective in participating in “O.G.” He wanted to help realize a vision of mass incarceration, “without an agenda, and to the extent that it can, without being tainted by a political bias. We wanted to do something more relevant than just some exercise in the liberal bleeding heart, you know?” he said. “I think there might be a temptation for some to kind of dismiss this in that way. That's sort of a bias too, but certainly, you know, our intent was to do something more nuanced than that, and certainly more helpful.”

In the following conversation, which has been edited for length and clarity, Wright discusses what it was like collaborating with Pendleton’s inmates for “O.G.” and the parallels between this work and last year’s “We Are Not Done Yet.”

Throughout your career, outside of your work in theater and film, you have worked with certain causes that are social justice related, such as last year’s “We Are Not Done Yet.” I’m curious to find out whether you noticed any thematic overlap in these projects, that may have informed the execution of “O.G.”

When artists or projects concern themselves with large issues of the day, often what we do is that we kind of sound the alarm, you know. We raise the flag over an issue and we leave the heavy lifting of needing to address those issues to someone else. In the case of this film, I think there's something woven into the practice of making it that speaks to solutions around the issues.

One, we worked intimately with these men. And that requires that we humanize them, that we work toward understanding who they were, how they were and why they were. And then as well, just through the act of coming together through this unlikely partnership we provided a kind of scaffolding, albeit temporary, for them to build something better.

Right.

And just that window through which they could view a more constructive citizenship, through which they could view a more constructive, creative, healthy version of themselves, I think, is positive. It speaks to ways in which we can engage with them and with these issues across sectors, in ways that are much healthier for society at large too.

I think that holds true with the project that I produced with the vets. Because it wasn't just about saying, "Hey, this is a problem, there's an epidemic here.” But, “there's also solutions available.” And the solutions in that film too were around creating spaces for intimate partnership and creating spaces in which that trauma could be converted into something therapeutic, something informative and something healthy.

I worked on the doc, or I went down to work on the staged readings that are featured in the doc with the vets, a couple of months after I finished working on this film, "O.G." And the overlaps were undeniable, the overlap between two sets of people who were trying to wrestle with the circumstances of the institutions that they had found themselves within.

For my character, transitioning out of that institution is like kind of a central personal crisis. Likewise for some members of the military, transitioning out too is a process that causes a great deal of anxiety, particularly if you're suffering from trauma as a result of your experiences.

And then, the larger overlap was around personal trauma. That's probably the most palpable pain inside that penitentiary and I became aware of was just this deep, all-pervasive sense of the trauma that these men had inflicted on others, but also the trauma that had been inflicted on them. The damage that had been built into them from the time they were small children. So, trauma is very much at the heart of the story that we tell in "O.G." And it just became so much more apparent to me as I worked with veterans of our military who were suffering from the consequences of their relationship to death — and also to sexual assault.

To switch gears a little bit to the actual artistic experience of this, you're quite a well-known actor and at this point when it comes many of the co-stars that you work with, if you're not already familiar with their work you have the ability to do a little bit of research before you go in to actually begin to work with them. This was a very different process, obviously, because aside from William Fichtner and a few other professional actors who appear in the project, the majority of the people you're working with are first time actors, including your co-star. So what was that like?

I was attracted to that idea because I'm kind of drawn to the idea of teaching, on some level. And so I kind of made it part of my responsibility on this thing to help shape their work and try to guide them toward realizing these characters.

But at the same time, clearly they know more about the realities around this story than I did. So I had to learn as much from them as they from me, if not more. But what I told them is that certainly there's some technical aspects working as an actor on film that I openly shared with them. And it was really was gratifying, and they were hungry to learn. They all, to a man, jumped into this project with incredible vigor and discipline.

Because they don't have a lot of opportunities, as you can imagine, that ask of them to be something more than the number . . . on their chest, on the pocket of their jumpsuits. Also, most of them are film buffs because they have a lot of time on their hands to watch movies. They've seen everything and they were intrigued about the process of putting the film together. Then, as well, for me, it was like having 100 expert consultants on that at any given time.

But also the writing of the script was a collaborative process. When I came on board, we had a draft of the script. But I went out, along with the director and writer, to meet with the men, to build the trust and also to exchange research with them so that we could flesh out this script in a more fully realized way. So yeah, it was a two-way street in terms of the creative nurturing that went into this the partnership, of working with these men. I've never been prouder of a group of collaborators on a film. It was pretty special, challenging and difficult, but ultimately a gratifying time with them.

Emerging from this, what were some of the things that perhaps you became a little bit more aware of in terms of the reality of life inside prison? Not only that, but in terms of the way it's popularly depicted? I pose that second question in light of the recent run of "Escape at Dannemora." Plus, soon we'll see the end of "Orange Is the New Black." Viewers can watch many shows about life inside prison, depicted with various degrees of realism.

There are a number of things that struck me. But one thing that I realize that we take for granted in our society is the relationship between incarceration and poverty. We make the easy assumption that if you come from certain communities, certain low-income communities, that you're just necessarily more prone to incarceration. And I started to question that when I was working with them, started to ask how it was that we could decouple the relationship of incarceration from the conditions of poverty.

Because there was almost a universal vein that ran through the stories of most of the men that I spoke with in there. Whether they were urban poor or rural poor — and in this prison in Indiana, it was a pretty evenly split demographic — they almost to a man told the same story of a broken family, of parental drug abuse, parental neglect, abandonment, of freedom too early on the streets by the time they were 10, 11, 12. Of involvement in illegal activity by the time they were teenagers. And then by 16 or 17, of absolute chaos, stories that you couldn't even begin to unravel the logic. And then, incarceration.

It was just like a checklist of things to do to wind up with a long-term sentence in a maximum security prison, and almost to a man they checked off those boxes identically.

In "Westworld," we talk about hosts being programmed toward behaving within certain loops. And it seemed to me that there was external programming. Of course they bear responsibility, too, for the path they took. But there was, you know, a degree of external programming of these individuals that was really kind of disturbing, Because I talked to so many of them and I quietly said to myself, "Man, this guy never had a chance."

That was the thing that was really most striking to me, is the way in which I guess all of us, whether we be citizens, whether we be legislators, whether we be members of law enforcement, educators, are complicit in creating the circumstances that lead toward incarceration and creating the individuals that wind up incarcerated.

As far the depictions of prison go, I think most of what we watch — and I haven't seen everything, obviously — but a lot of what we watch is, is akin to the rodeo down in Angola, the prison that they used to have, or still have, I'm not sure. But where we kind of view these conditions as entertainment, starting with all the kind of bastardized documentaries on incarceration that were born out of "Scared Straight" back in the '70s. That was a genuinely powerful depiction, but it has kind of devolved into sensationalized, prurient window on people who, for perhaps valid reasons, have found themselves on the other side of the wall from society.

And perhaps understandably on some level, I guess we really don't care what happens over there. That's the reason that we lock up folks like this. But at the same time, if we're really going to try to crack the epidemic of crime and violence and incarceration in America, then we might want to take a more nuanced and humanizing look at these men.

Because it was my experience that they have all of the answers towards the solution to these things. They know their own personal stories, and their personal stories tell the stories of those young Americans who are in the first chapters of writing similar stories. It was heavy in there, but it was at the same time it was kind of mind-opening too.

Shares