After the Christchurch massacre, New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern struck exactly the right tone, donning a hijab in solidarity with the victims and winning worldwide praise. Australia’s Senate overwhelmingly censured the lone lawmaker who blamed New Zealand’s Muslim immigrants themselves for the attack. But things are tragically different here in America, where President Trump’s promotion of a vicious smear campaign has endangered the life of America’s first hijab-wearing Muslim member of Congress, Rep. Ilhan Omar, D-Minn.

Trump used an out-of-context quote — from a speech about claiming full citizenship, that as Peter Beinart said, “beautifully evoked what I treasure about being an American Jew” — to try to make Omar seem as callous and manipulative of 9/11 as Trump himself. When Trump was asked on Sept. 11, 2001, whether a building he owned had sustained any damage, he responded by saying it had been “the second-tallest building in downtown Manhattan … and now it’s the tallest.”

Trump lied about Omar. But she told the truth about him.

“Since the president’s tweet,” Omar said in an online statement, “I have experienced an increase in direct threats on my life — many directly referencing or replying to the president’s video. Violent crimes and other acts of hate by right-wing extremists and white nationalists are on the rise in this country and around the world. … Counties that hosted a 2016 Trump rally saw a 226 percent increase in hate crimes in the months following the rally. And assaults increase when cities host Trump rallies.”

Democrats could act much more forcefully to put a stop to this. All 108 Democratic women in Congress could show up wearing hijabs when Congress reconvenes after the April recess. But no one’s expecting anything like that — in part because the smear campaign endangering Omar’s life has been decades in the making, and it can’t be countered overnight. But it can be understood — and from shared understanding, concerted action can come.

In the New Yorker, Masha Gessen has drawn parallels between schoolyard bullying and political violence. “In modern states ruled by autocrats, or aspiring autocrats, political violence is dispersed and delegated. Its first weapons are ridicule and ostracism,” she wrote, citing three prominent examples from Vladimir Putin’s Russia. It’s clearly a warning we should heed, but it doesn’t specifically addressing how the process works in America today, which has a very different history than Putin’s Russia. With Gessen’s broader lesson in mind, we need to look sharply at ourselves.

Creating a controversy — the arsonist’s art

On Reliable Sources, CNN’s Brian Stelter provided a useful starting point for understanding the generation of this latest attack. “You probably heard a lot about Congresswoman Ilhan Omar this week. But do you know why? Do know how it started?” Stelter asked. “Controversies don’t just erupt like a bolt of lightning sparking a fire. No. Controversies are created like an arsonist lighting a match,” and too often news coverage “starts mid-story. We say there is a controversy brewing between these two people, but we leave out the most important part, the lighting of the match.”

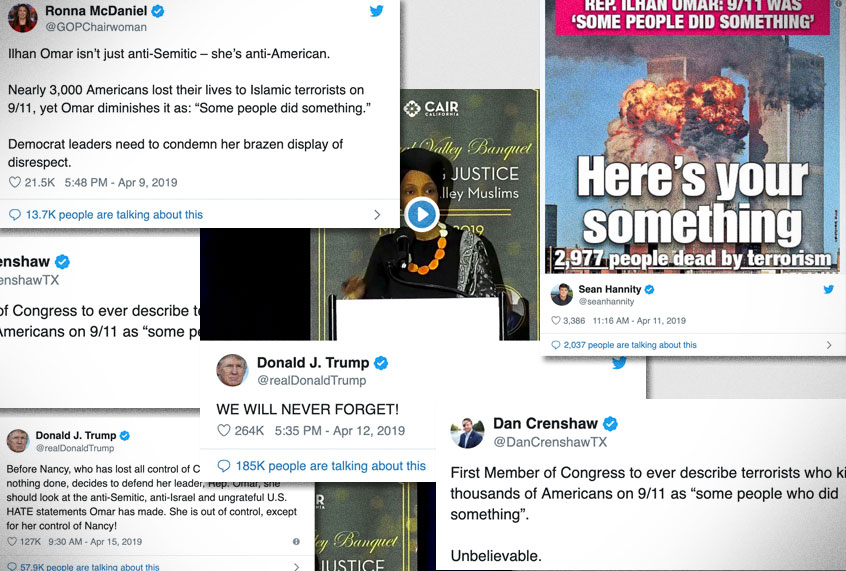

Last month, Omar gave a speech to the Council on American Islamic Relations, focused on protecting civil liberties. The speech was little-noticed until, on Monday, April 8, the Daily Caller (a right-wing online publication co-founded by Tucker Carlson) posted a four-minute video to YouTube. After that, Stelter reported:

[A]n Australian man who calls himself a Muslim scholar and is very active on Twitter sets the frame for a week’s worth of news conference. The framing is that Omar was downplaying 9/11.

His tweet took off and spread [across] the right-wing websites. It was all over the sites by Tuesday. Then on Tuesday night, Sean Hannity brought the video to television.

By the end of the week, it had been hysterically distorted on the cover of the New York Post and in a video pinned to the top of Trump’s Twitter page. “But there is something bigger going on here with this story,” Stelter said. “It tells us something about the right-wing rage machine and how news stories are set.”

That and more. There’s an even bigger two-fold story behind the story: how that right-wing rage machine came to be, and how Islamophobia came to be such an integral part of it, when it previously hadn’t been, as data sociologist Christopher Bail explained in “Terrified: How Anti-Muslim Fringe Organizations Became Mainstream.”

In a Salon interview, Bail noted that Muslims voted for George W. Bush by a margin of three to one in the 2000 election, and that Muslim leaders later had private audiences with both Bush and Vice President Dick Cheney. It may seem hard to believe now, but demonizing Muslims was not part of the GOP playbook at the time, and ersatz experts — like the aforementioned “Muslim scholar” — were not hot media celebrities. It was a different world.

The rage machine: Transmitting hate from margin to mainstream

But not when it comes to the rage machine, which is why we take up that story first. There’s no better expert than journalist and author David Neiwert in explaining how manufactured outrage has become a method for injecting fringe ideological views into the mainstream. He explored the subject in detail in his prize-winning online essay, “Rush, Newspeak and Fascism,” and further developed in his book, “The “Eliminationists: How Hate Talk Radicalized the American Right.”

“The transmission process for these ideas and talking points works the same as it did in the 1930s when the America First Committee regurgitated talking points from Hitler’s Nazis, or when Rush Limbaugh began convincing half of America that liberalism was the essence of evil itself in the ’90s,” Neiwert told Salon. (He got the idea for the term from a 1941 publication, “The America First Committee: The Nazi Transmission Belt.”)

Neiwert’s “Newspeak” essay adds more detail:

To the far right, [Bill] Clinton embodied the totalitarian threat of the New World Order, a slimy leader in the conspiracy to enslave all mankind. To conservatives, he was simply an unanswerable political threat for whom no level of invective could be too vicious. Moreover, he was the last barrier to their complete control of every branch of the federal government. …

Ideas and agendas began floating from one sector to the other in increasing volume around 1994. … This crossover is facilitated by figures I call “transmitters” — ostensibly mainstream conservatives who seem to cull ideas that often have their origins on the far right, strip them of any obviously pernicious content, and present them as “conservative” arguments.

This has become so commonplace and pervasive in recent decades, that we hardly recognize it as something that wasn’t nationally organized for most of the period between the 1930s and the 1990s. The process makes hate more palatable — but no less dangerous, Neiwert told Salon:

Essentially, it originates as a claim or talking point concocted by far-right extremists, which means it’s congenial to their ideas and promotes their agenda, even if the usual bigotry or violent intent are sublimated and not readily apparent. Any of these points that are “scrubbed” of these latter elements are readily picked up and transmitted into mainstream venues by right-wing pundits, who disingenuously pretend that the underlying toxic intent isn’t there.

However, once the point reaches wider circulation, and the public responds as intended, then this underlying purpose becomes manifest, as they have in Omar’s case, where the purpose is not just to counter her speech but to create an ongoing physical threat against her.

The process potentially poisons everyone along the way:

As they accumulate, the people who absorb these ideas from the mainstream are themselves gradually radicalized into a belief system that is much farther right than they ever envisioned themselves becoming.

The difference between then and now is the speed with which it happens. Before, it would sometimes take as long as several months for far-right ideas to be transmitted into the mainstream via radio, faxes and email forwards. Now, on social media, the transmission can occur within a very short timespan, sometimes as short as a single day. There is almost no time to sufficiently respond in these situations. And when the president himself become the transmitter in chief, the spread and adoption of these extremist ideas as conservative conventional wisdom becomes impossible to overcome.

The fact that Ilhan Omar has been the subject of multiple swiftly-developing “controversies” in a few short months is not so much because of who she is — though she is the perfect target for Trumpian “conservativism” —but because of how quickly the process now moves and how well-oiled the machinery has become.

Creating the Islamophobia-industrial complex

The second side of the story, the way Islamophobia became involved, is more complex. Bail’s book advances “a new theory that explains how cultural, social, psychological, and structural processes can combine to shape the evolution of shared understandings of social problems in the wake of crises, such as the September 11 attacks,” he writes. We can think of it in three stages.

First, the crisis creates an opening that fringe groups can exploit:

Such events provide fringe organizations with the opportunity to exploit the emotional bias of the media. Media amplification of emotional fringe organizations creates the misperception that such groups have substantial support and therefore deserved reprimand.

Before 9/11, there was an emerging mainstream discourse about Islam, shaped by a population of civil society groups, both Muslim, like CAIR, and non-Muslim, like the World Council of Churches and the World Jewish Congress. “These ecumenical and interdenominational collaborations frequently highlighted the shared Abrahamic origin of Islam, Christianity and Judaism in public showings of support for mainstream Muslim American organizations,” Bail notes. “This mainstream discourse unanimously denounced terrorism in the name of Islam — even if many mainstream organizations blamed U.S. foreign policy for the existence of such extremism in the first place.”

After 9/11, Bail said in our interview, “people continued to produce overwhelmingly pro-Muslim messages about Islam, but the media gravitated to the small group of fringe organizations, because, I argue, of the emotional tenor of their messages” which validated feelings of fearfulness and terror.

These fringe organizations knew relatively little about Islam, and were driven by preconceptions. “Many of these groups were composed of hawkish neoconservatives who turned their sites toward dictatorships in the Muslim world as the Cold War faded into history,” Bail wrote. “Indeed several of these organizations began to describe Islam as a dangerous totalitarian ideology not unlike Leninism.” As the saying goes, “When all you have is a hammer, all you see is nails.”

Second, mainstream attempts to respond can backfire, creating even deeper openings:

Yet when mainstream organizations angrily denounce the fringe they only further increase the profile of these peripheral actors within the public sphere. This unintended consequence creates tension and splintering within the mainstream — but also gives fringe organizations the visibility necessary to routinize their shared emotions into networks with more powerful organizations that help them raise funds that consolidate their capacity to create cultural change.

When mainstream organizations denounced terrorism, they were almost universally ignored. “I have this line from a world leader in the book,” Bail said in the interview, “he denounces terrorism so often that he could ‘do it in his sleep.’ But you know, the media is not covering it because he’s not doing it in an angry sensational way that causes the celebrity of the fringe.” But the media does pay attention when mainstream groups respond forcefully to false accusations from the fringe, sometimes accusing them of condoning or even supporting terrorism.

Most significantly, fringe groups “accumulated more than $245 million in contributions in the decade that followed” 9/11, primarily from nine philanthropic foundations. “Anti-Muslim organizations won access to these foundations via their social network ties to mainstream conservative organizations such as the AEI [American Enterprise Institute] and the Hudson Institute.” This massive funding is a large part of the story of how Islamophobia became integral to the right-wing rage machine.

Third, the former fringe groups now have the ability to reshape the political landscape:

From this privileged position these once obscure organizations can attack the legitimacy of the mainstream precisely as it begins to tear itself apart. With time, these countervailing forces reshape the cultural environment — or the total population of groups competing to shape public discourse about social problems — and fringe organizations “drift” into the mainstream.

The end result of this process is a profound perversion of public understanding: about Islam, about terrorism, about America, and about how we got here, as well.

The course was already set a decade ago. “In September 2006, two congressional subcommittees began evaluating the risk of radicalization among Muslim Americans,” Bail wrote. “Not a single mainstream Muslim American organization was invited to participate.” The same was true of a Senate investigation of radicalization chaired by Joe Lieberman and Susan Collins from 2006 through 2008.

Outside Washington, Bail discusses the spread of fear-based fantasy campaigns — such as the introduction of anti-Sharia law bills in state legislatures — as well anti-mosque activity, both violent and nonviolent. The campaigns to accomplish these ends helped to further establish a profoundly different political sphere in which anti-Muslim prejudice has become completely normalized in the Republican base, and even beyond.

Demonizing Ilhan Omar

All the above form the background for the repeated generation of controversies targeting Omar. Of course one can’t neglect that she’s a black immigrant woman as well as a Muslim — all of which contribute to making her a target. But those other factors have long histories and widely diffuse ways of working. They make her especially inviting for those attacking her, but are not as integral to the distinctive attack machine that’s trained most of the fire against her.

In the beginning, the attacks on Omar came cloaked in the pretense of combating anti-Semitism, via the same sort of hysteria over out-of-context snippets, divorced from the actual arguments she was making. I call it a pretense, because, as Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez pointed out on Twitter, a genuine concern would call in before calling out. “’Calling out’ is one of the measures of last resort, not 1st or 2nd resort,” she noted. If what you’re up to is more than pretense, that is.

But now that pretense has been utterly stripped away. After Trump’s Twitter attack on Omar, all bets were off. When the Cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris was ravaged by fire on April 15, right-wing conspiracies flooded social media, framing it as an Islamic attack on the West, as documented by Talia Lavin at the Washington Post.

“The conspiracy theorizing began almost as soon as the blaze did,” Lavin wrote, “Their prevailing view was nearly identical and, apparently, completely false: that the fire was deliberate and most probably set by Muslims.” What’s more, there was a whole sub-genre focused on Omar:

Blogger David Futrelle, an expert on the worst of the Web, gathered dozens of tweets claiming that Omar was either celebrating the fire (variously “smiling inside,” “happy as a muslim terrorist,” “giddy and laughing”) or, somehow, had caused it. Multiple accounts questioned whether Omar was in Paris and whether her relatives had set the fire or asserted falsely that she was affiliated with a Muslim group that had set it.

Any pretense of a connection to reality is now gone with the wind. This is where we are today, and those who have attacked Omar in the past, unwittingly aiding the rage machine, owe her an apology. Needless to say, she won’t get one.

At Vox, Zack Beauchamp wrote that it was “time for Ilhan Omar’s critics to stand with her against Trump’s attacks,” but his first rhetorical move was to renew his attack on folks like me:

I’ve argued that the defenses of her language on the left, even from some Jewish leftists, bear a worrying similarity to the rationalizations used to hide the cancerous growth of anti-Semitism in the British Labour Party under leader Jeremy Corbyn.

In my defense of Omar, I quoted J Street president Jeremy Ben-Ami, who said on MSNBC:

If you’re going to have a serious discussion about hate and intolerance in this country, let’s start at the top. Let’s start by having a House discussion about the president’s intolerance and his racism. Let’s have a discussion about the xenophobia and the racism that’s coming from the other side of the aisle. And let’s stop using the discussion of anti-Semitism as a way of avoiding a real discussion about policy towards Israel and Palestine, and the issues that are actually on the table about occupation and the treatment of Palestinians.

That’s not a rationalization meant to hide the growth of anti-Semitism on the left. It’s a rational attempt to refocus our attention where it belongs. That would be one of the surest ways of combating anti-Semitism, which, as I argued in “Eight mistakes the media makes about anti-Semitism in America today,” has a long history of association with the right, and is central to white nationalist ideology Trump relies on to rally his base. It was also, obviously, central to the earliest incarnation of the transmission belt described by Neiwert.

I’ve also argued that it’s seriously mistaken to reduce discussion of anti-Semitism to a matter of mere “tropes,” a profound trivialization that only benefits the real anti-Semites like Trump. As I noted, the speech from which one such “trope” controversy was generated began with Omar doing the exact opposite of treating Jews as “the other.” Instead she underscored the connections between Jews and Palestinians — and to her own experience:

I know that I have a huge Jewish constituency, and you know, every time I meet with them they share stories of [the] safety and sanctuary that they would love for the people of Israel, and most of the time when we’re having the conversation, there is no actual relative that they speak of, and there still is lots of emotion that comes through because it’s family, right? Like my children still speak of Somalia with passion and compassion even though they don’t have a family member there.

But we never really allow space for the stories of Palestinians seeking safety and sanctuary to be uplifted. And to me, it is the dehumanization and the silencing of a particular pain and suffering of people, [it] should not be OK and normal. And you can’t be in the practice of humanizing and uplifting the suffering of one, if you’re not willing to do that for everyone.

This is the voice, the consciousness and the conscience that Trump and the right-wing rage machine want to destroy. Ilhan Omar is the voice of the best of America.