The 2020 race for the Democratic presidential nomination is already historic, featuring a racially and gender diverse field of candidates without precedent in the United States.

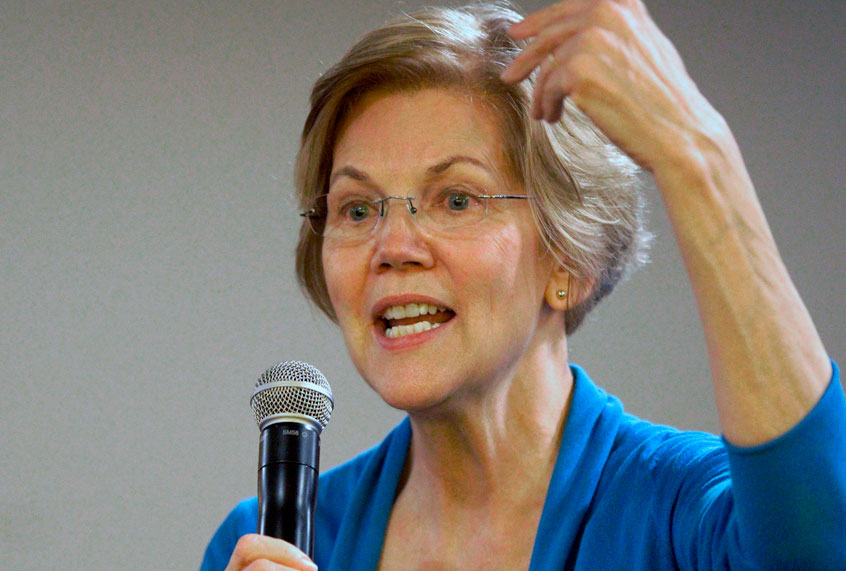

But for many of those cheering on this development, the reality of the polling in the race so far has been sobering. Most surveys find the field led by former Vice President Joe Biden and Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders, two white men who look conspicuously like the vast majority of previous presidential candidates. It’s been hard for qualified women, like Sens. Elizabeth Warren, D-MA., Amy Klobuchar, D-MN., Kamala Harris, D-CA., and Kirsten Gillibrand, D-NY., to garner any support in the double digits.

Meanwhile, two candidates who are much newer to the national stage but have yet made waves in the race are Mayor Pete Buttigieg and Beto O’Rourke, two more white men. (Buttigieg, though, would be a historic candidate in his own right as an openly gay elected official.)

I spoke to philosopher Kate Manne of Cornell University, who wrote a book on a conceptual account of misogyny, to discuss the influence of gender bias in the primary race.

In Manne’s “Down Girl: The Logic of Misogyny,” now available in paperback, she analyzed Hillary Clinton’s presidential run and argued that misogyny shaped the way she was perceived. But the 2020 Democratic primary, she told me, is an even “cleaner case” to see how gender bias affects politics.

“If you look at the trend of white men in this race getting a lot of early support in terms of both polling numbers and donations — as well as positive media coverage — I think it begins to look harder to argue that there aren’t gender biases in play,” she explained.

While Clinton was a single candidate with unique circumstances, the wider field and variety of candidates make it much easier to infer that misogyny is having an effect on the race.

But some specific phenomena also seem to suggest implicit gender bias. Manne noted that a recent poll found that about a quarter of people who support Bernie Sanders in the primary would switch over and vote for President Donald Trump if Warren became the Democratic nominee. Such a position is difficult to justify if your main concern is policies and ideology — both Trump and Sanders would both tell you that the Vermont senator has much more in common with Warren — but it’s more understandable if a significant portion of the population has trouble viewing a woman in the preeminent leadership role in the country.

In Manne’s understanding of misogyny, gender bias isn’t merely about animus or condescension toward women. It often consists of seeing women as appropriately suited to particular types of roles in society. Often, these roles are focused around caring, nurturing, or serving others. When women step out of the roles society expects of them, they can be subject to a misogynistic backlash.

She argued that this is a plausible explanation of what happened to Hillary Clinton in 2016. It’s easy to think of Clinton now as the embattled and bruised 2016 presidential candidate, but Manne pointed out that she was a particularly popular secretary of State. When she left that office, she had a 69 percent approval rating.

“Women do quite well politically when they’re perceived to be, or actually in service positions,” she told me. “I think women are actually allowed to have quite a bit of power as long as it’s in service of those who are perceived as entitled to their feminine-coded services.”

So when Clinton accepted the offer of President Barack Obama, who had defeated her in the 2008 presidential primary, to lead the State Department, she enjoyed widespread approval. She served under Obama and she served the country, managing relationships with foreign leaders.

But public perception changed when it became clear she was seeking the presidency.

“Where women tend to really face misogyny, I think, is where they’re perceived as insufficiently caring, insufficiently nurturing. A classic example of that is Clinton being quite popular as secretary of State, but facing disproportionate suspicion over Benghazi,” Manne said. She also argued that, by the time 2016 rolled around, there was a “perception of her trying to take away something to which a white man would historically be entitled.”

We should be wary of similar dynamics playing out in 2020. But Manne is clear that she has little interest in accusing particular people or voters of misogyny. Any particular case can be challenging to assess, and the public accusation would likely do little to help in any event, even if it might help in other circumstances. And yet voters and observers of the race should be aware of the way gender biases can creep into their assessments of candidates, she argued.

“Those perceptions are usually unwitting and unconscious, but I do think they’re prevalent,” she said.

One way they might present themselves is in how different kinds of actions by candidates are interpreted. Clinton, for example, won over voters during her “listening tour” when she was running to be a U.S. senator in New York. But this kind of female-coded campaign tactic doesn’t scale-up well to a presidential race in the way that holding massive rallies all about the candidate does — especially in the iconic manner both Trump and Sanders have become known for.

“[For] women in public life, there are powerful incentives to package themselves as service providers,” said Manne. But this can pose obstacles when you’re seeking the most powerful office in the country that is subordinate to no one. The presidency is “the ultimate masculine-coded authority position,” she explained.

“It’s hard to be perceived as wanting to serve rather than wanting to preside — when you’re running for president,” she said. “There’s much more taste for men taking to the lectern … and holding forth about their ideas and their vision.”

This also helps explain why candidates like O’Rourke and Buttigieg — or even Trump — are able to burst on to the national scene out of nowhere and gain traction, something few if any female candidates have yet to do. Coming to the race with less national baggage and a shorter public record offers lots of advantages, because there’s less of a history to attack, and the candidate is seen as offering a change of pace to the Washington status quo. But the country is much less likely to excuse the inexperience of a female newcomer seeking a role we implicitly assume will go to a man. Women are expected to demonstrate that they can serve the public, whereas some men can show up and declare that they’re ready to lead.

But Manne argued that these prejudices are misguided, and we should work to overcome them. Given two candidates who were both well-qualified, she told me that there would be strong reasons to choose a woman over a man. Simply representing half of the population that has been unerringly excluded from the presidency would be a major step forward for the country. And a woman could bring experience to the role — like the experience of combing motherhood and work — that has been entirely absent from the resumes of past presidents.