Most advances in technology have been for the good and occasionally are even transformative. Being able to travel long distances by plane rather than trains or cars was a big one. And then came the frost-free freezer! My first couple of refrigerators didn’t have one. I remember opening the freezer looking for the frozen peas and finding them locked in a solid mass of hairy white frost. Every four or five months, you had to turn the thing off and open the freezer and put a couple of pots of boiled water in there to speed up the defrosting. That never worked very well, so you’d end up standing there and chipping at the stuff with an ice pick with chunks of frost flying all over the kitchen. Remember ice picks? I didn’t think so.

As a writer, I’d be remiss if I didn’t pay homage to the arrival of the personal computer and the word processor. No more feeding sheets of paper backed by carbon paper with attached onion skin for copies. No more penciling out mistakes and penciling in changes, with arrows pointing to new clauses or phrases in the margins. I kind of miss the satisfaction of watching a pile of pages grow taller on the desk when I wrote my first couple of novels . . . but not enough to go back to typing on an IBM Model D, a one-horsepower monster that shook the whole desk every time you hit return and the carriage flew across the top of the thing. Before I had an electric typewriter, I pounded out every word I ever wrote on a little Olivetti Lettre 22 that I still have. I carried it everywhere – trains, planes, cabs, jeeps, even an armored personnel carrier or two. One time I stuffed it between my body and the door of an Oldsmobile 88 when we were being shot at by a pick-up full of Fatah fighters in Southern Lebanon, hoping the thing would stop a bullet. It might have, actually. Every piece of the thing is steel. Couldn’t say that about the laptop on which I’m writing this.

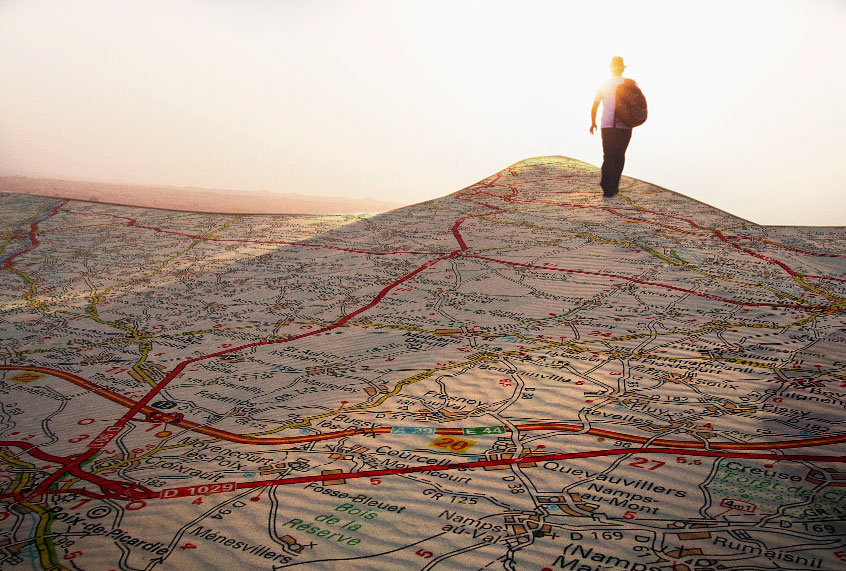

And then came GPS. We’re going to end up paying big-time for the disuse of maps and the ubiquity of GPS, I’m afraid. You don’t need one in your car anymore, because everywhere you go, you’re carrying one in your pocket. Every smartphone is outfitted with Global Positioning Satellite technology, and unless you somehow disable it, the goddamn thing is on all the time. It’s not just the phone company who knows where you are. Have you walked down the aisle in Target lately? You pass the kitchen section, and if you glance at Facebook, there’s an ad for a fucking Keurig winking at you. Comes with a dozen of the stupid little plastic cups filled with hazelnut or vanilla or caramel “coffee.” On special right now! Only $59.95! Drive past Taco Bell, and an ad for the new Doritos Cheesy Gordita taco comes up.

All that stuff is a pain in the ass, but the disappearance of maps that GPS is forcing on us really concerns me. Have you tried to find a map lately? Don’t bother stopping at your local Shell, because gas stations don’t sell them anymore. Borders Books used to have shelves of maps in the travel section. Paris! Berlin! Rome! Every time I would leave on a trip as a journalist, I’d stop by the Borders or Waldenbooks and pick up maps of the states, or countries I was headed for, and city maps, too. I remembered the time I took off from JFK to cover a Dylan and the Band concert in L.A., only to land and rent a car and not have a clue where I was or where I was going. Never again. I had two or three bookshelves in my study at home that held nothing but maps. I could have given you directions to get thick Turkish coffee in the souk in fucking Baalbek, Lebanon if that’s where you wanted to go.

I learned to read a map when I was 7 years old, in the second grade. My father was an Army officer, and the first thing he did when we moved from Tennessee to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, was sit down at the dining room table and draw a map on a sheet of 11 by 14 paper. He drew the whole area around our new set of quarters: our apartment in a World War II-era barracks was a little black rectangle at the end of a street; there was the playground, and beyond, an area of hilly woods and a creek and a baseball diamond. He outlined the hills in brown contour lines, showing their steepness as the lines of elevation got closer together, finally reaching a small circle at the peak. The creek was blue. He drew the old unused railroad track as parallel lines in black with tiny cross ties.

He taught us all the symbols, including the contour lines showing the hills, and then he took the finished map and covered it with a sheet clear plastic known in those days as “visqueen” and taped it to the front of the refrigerator. He tied a red grease pencil to a piece of string and taped it next to the map. My brother and I were instructed to put a red “X” where we were going to play when we got out of school every day, and there was hell to pay if our mother or father went looking for us and we weren’t there.

The first time I had to follow a real map on my own was in 1964, when a friend and I set off from Carlisle, Pennsylvania and rode our ten-speed bikes to New York City and the Worlds Fair, and then turned west and rode back through Carlisle and onward, ending up where my friend lived in Manhattan, Kansas, the geographical center of the continental United States. We took maps of all the states we rode through, and all the big cities like Philly, Pittsburgh, Indianapolis, St. Louis, and Kansas City. We rode those bikes about 1,600 miles and it took us the better part of two months, with stops to see the sights of the big city and visit relatives. We couldn’t take one of the tunnels into Manhattan.

We studied a map of the New York City area to find a little bridge we could ride our bikes across to Staten Island, so we could take the ferry and ride our bikes through the city to the 32nd Street YMCA where we got rooms for 75 cents. Then there was the time we were riding through the endless Ohio farmland on old U.S. Route 40 and I looked up ahead and saw the approach of a gigantic thunderhead and looked down at the map mounted on my handlebars and saw we had 12 miles to reach shelter in the next town. We pedaled faster, but we were going to get soaked. The map told us so.

I studied map reading at West Point and got good at it. At the Infantry School at Fort Benning, Georgia, I finished a lengthy map reading course 45 minutes ahead of the next guy in my class. I had learned the trick of not paying attention to the compass and following the terrain features on the map. If you could look at the map and envision a saddle between two low hills with a creek a hundred yards beyond, you could find the marked tree that was your target and move on to the next one —– five or six in all, separated by miles of thick, featureless pine forest. The trick was to trust your reading of the terrain and your stepped-out estimation of distance. The compass could mislead you because you could never follow the azimuth you started out on. You had to shoot a new one every time you moved around an obstacle, like a boulder or a clump of trees too close together to pass through. But the terrain never lied, and if you could read it, the map didn’t lie either.

Being able to read maps was especially important in the military because getting lost was not an option, and not being able to locate yourself precisely could put you in danger of being hit with friendly fire in combat. I saw exactly one map the entire month I was in Iraq in 2003. Every vehicle was equipped with GPS, and the helicopters I took had “Blue Force Tracker” flat-screens that could call up Google Earth-style images of the ground we flew over, even side-looking images of buildings so precise you could see the colors of doors and even street addresses if they were marked.

But what if somebody…say, the Russians or the Chinese…figure out a way to jam the satellites that keep all the GPS shit operating, and those screens in the helicopters and GPS locators in the Humvees go black? I’m sure the Army has maps to use as back-ups, but if you don’t read the goddamn things regularly, you lose touch with the largely instinctual ability to read terrain and maintain a good-old-fashioned sense of direction. How about this: it’s the middle of the night, there’s no moon, you’re two miles from the nearest road, you’re moving through a freshly-plowed field, and the last thing you remember seeing was a group of three unoccupied mud huts next to an irrigation canal, but that was a couple of miles ago. Your GPS goes black.

Which way is west, the direction of the Syrian border? Which way were those mud huts you passed, where you could take shelter? Where’s that damn irrigation canal that was clearly marked on your GPS and would be on a map . . . …but where’s the map? What happened to that damn GPS? It’s not the batteries, you checked them. The thing just stopped working. Six more hours until daylight. You look behind you. You can’t even see the other Humvees in the convoy, it’s so dark.

Now imagine that scenario writ large. You’re in the war room in the Pentagon, and you can’t “see” the satellite images of where you’ve got 15,000 troops on the ground. Your helicopters can’t “see” so they can’t fly. Neither can your fighters. Your artillery units can’t aim their Howitzers because they can’t “see” their targets using GPS to fix and fire at them. Those zillion dollar guided missiles can’t be guided, so they’re useless.

Well, at least the radios work. You can talk to the units under your command, but you don’t know where they are, and neither do they. Where’s the damn ice pick? The whole military is as frozen in place as that package of peas, and just about as useful.