Jared Diamond is not afraid of big ideas. He has tackled such subjects as evolutionary psychology, the reasons why the West rose to global dominance, the lessons to be learned from “traditional societies” and the relationship between environmental change and the decline of ancient civilizations. and why ancient societies fell into decline.

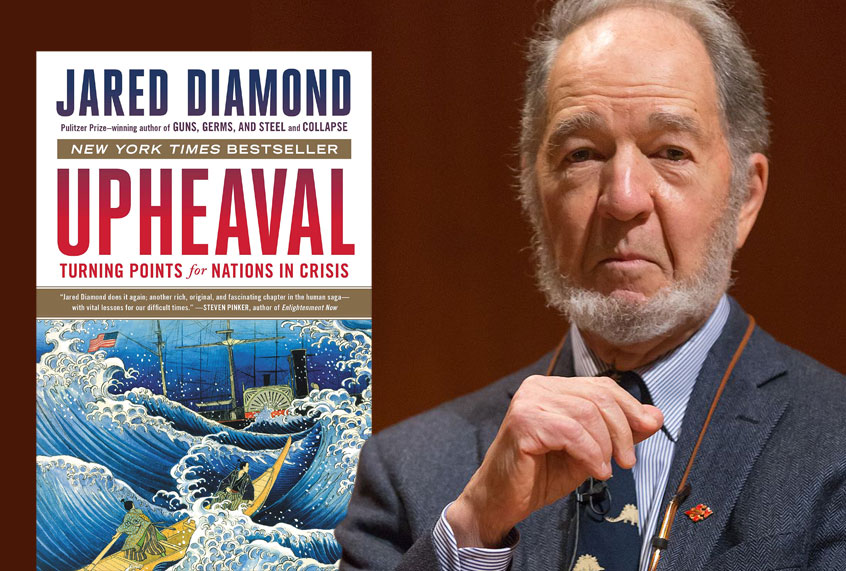

Diamond has been elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the American Philosophical Society, and the National Academy of Sciences. He has been awarded a MacArthur Foundation Fellowship as well as the National Medal of Science. His bestselling book “Guns, Germs and Steel” won the Pulitzer Prize.

Diamond is currently a professor of geography at the University of California, Los Angeles. His new book “Upheaval: Turning Points for Nations in Crisis” examines how nations successfully adapt to change — or do not, and then fall into a spiral of failure and rapid decline.

How do countries choose to succeed or fail? How do Trumpism, political polarization and other types of dysfunction imperil America’s leadership role in the world? How can countries most successfully manage social and political change? What are some pitfalls to avoid? Could America soon become a failed democracy, like Chile or Indonesia? Is immigration a net positive or negative for the United States? How does dishonesty lead to a nation’s collapse? How does the concept of “national identity” influence a nation’s success or failure in difficult times? Is the United States in decline — and will China inevitably become this century’s dominant next “superpower?”

I sought to address these questions and others in my recent conversation with Jared Diamond. This interview has been edited for length and clarity. My conversation with Jared Diamond can also be listened to through the player below.

When you look at the world now, what problems concern you most?

Those big problems would include nuclear risk, climate change, sustainable resource use and inequality around the world.

In terms of America’s leadership class, what are you most concerned about?

I’m not concerned just about the elites. I’m concerned about the whole spectrum of the United States, the polarization within the electorate as well as geographic polarization, income polarization, political polarization, and the polarization of our legislators.

How does a country’s “national character” fit into whether or how a given society survives a time of crisis?

Instead of talking about national character, the phrase that I use in my work and thinking is “national identity.” I gradually realized that national identity for different countries depends on different things. For example, I’ve just come back from several weeks in Italy, where I was teaching at Rome’s Social Science University. Italians have a national identity. But what they are proud about is not what Americans are proud about. Italians are proud about their style, their history of the Roman Empire, their cuisine, their friendliness, their social relationships with other Italians and their great art, of course.

Whereas for people from Finland, their national identity depends upon their unique language and having survived war against the Soviet Union. In the United States, our national identity depends upon our having conquered a continent and our being the most powerful country in the world. In Germany, national identity used to depend upon military feats which are now regarded as evil. German national identity now depends upon some features of German national character, namely the role of the community where in many cases it takes precedence over the role of the individual in society. Germans have great pride in their art and music.

How do countries respond to a crisis in national identity and meaning? Donald Trump and his movement are one such crisis afflicting the United States in this moment.

Slowly. My new book examines national crises from the perspective of personal crises in identity. When we change our personal identities, we can work through it more quickly because it involves just one person, us. National identities inevitably get changed more slowly because it requires arriving at a consensus for a whole country.

For example, in the book I discuss the slow change in national identity for Australia, which took place over several decades from the time I first visited Australia in 1964. Since then, Australians have gradually been discarding what had been their national identity. This had been based on: “We, Australians being loyal British citizens, we are the British outpost near Asia.” Well, that identity gradually got discarded as a result of events in 1941 and 1942 in World War II, then Britain’s application to the European Union, and Australia’s increasing trade with Asia. This process took decades and decades.

Similarly, with the United States we are changing our vision of the country’s national identity. It’s going to take us time, so it will happen slowly. I do not think it is going to take the country several decades as it did Australia, but it certainly is going to take more than a year or two.

In what ways should a country navigate such times of change in order to be successful? How can the United States manage this in a healthy way?

A starting point would be “We need to be honest.” There is a big deficit in honesty in the United States at present in talking about our country’s problems.

A very specific example: a lack of honesty about immigration. There are these arguments about putting up a wall on the Mexican border. Well, the fact is that the great majority of people who are in the United States as so-called illegal immigrants have not come across the Mexican border. Instead, they’ve come to the United States on legal visas and then they’ve overstayed them. Therefore, the discussion about the wall is tangential. In addition, if we are concerned about people coming across the Mexican border, the preferred ways to get across the Mexican border are to wade across the Rio Grande or to go through tunnels. These proposals about Trump’s wall are a prime example of dishonesty and ignoring the facts.

What are other examples of things that the United States and its leaders and people are dishonest about?

We need to be honest about what is good about the United States and what needs to be changed. Things that are good include that we are still the most powerful and richest country in the world. America has wonderful geography. The United States is protected on two sides by oceans and on the other two sides by non-threatening neighbors. We have the richest farmland in the world. We have the best institutions of higher education in the world. We have a long history of freedom, relatively speaking. There are gaps in our freedom, of course, but compared to other countries, the United States has a track record of freedom. Those are things that we as a people can be proud of.

We can also be proud of the crises that we as a people have overcome in the past, such as the Civil War. I grew up in World War II, and we survived that. As a country, the United States survived the arguments over the civil rights movement. There is so much that we Americans can be proud of. We do not need to talk about making America great again. America is already great. There are not new things that have to be added to make America. America’s already great. There are mistakes that we’re making, though, and we’d better sort those out.

Of course you can’t predict the future. But what are some system shocks that you believe could cause great change and disruption in the United States in the near term?

Possible sources of unexpected big shocks, of course, would include another terrorist attack. Still another would be a really big massacre within the United States. Getting 59 people killed or 11 people killed doesn’t attract attention anymore in America. Maybe getting 530 people killed, not by a World Trade Center-like attack, but by some gunman within the United States. If the 530 people killed were schoolchildren, that might attract attention. A big weather shock would convince even diehard disbelievers in climate change that there really is a problem.

I’m concerned that the United States is no longer dreaming big any more. The country has become so insular and narrow-minded, turned inward. Is that a common trait for societies in crisis?

It’s true that during the 1960s we had the big goal of going to the Moon and we achieved that. There is a widespread view, particularly in conservative circles in the United States, that for government to do something is “socialism” and that “socialism” is bad. But the fact is that ever since the first central government arose 5,400 years ago, government can do things that cannot be done properly or well by private interests. Private interests do not do something with their own resources, generally, that do not bring them direct benefits. Instead, things that produce diffuse benefits — such as school systems or national health systems or national support for scientific research — are what government is for. Unfortunately there is an increasingly widespread view in the United States today against the role of government in providing those benefits and services.

What are some lessons from history about how the United States can make good decisions about this moment of change?

I would start off with the worst problem in the United States today — the breakdown of political compromise. I was living in Chile a few years before the military coup d’état [in 1973] when Chileans were proud of their democracy. They didn’t foresee that Chilean democracy would be finished within seven years and they would have a military dictatorship which smashed world records for sadism.

A great and ambitious plan for America would be to raise seriously the dangers of a breakdown in political compromise, which has the potential to ruin America as it did Chile and Indonesia. We must work hard and make sure that such an outcome does not happen here.

Donald Trump and many of his allies and supporters want to change immigration policies to keep nonwhites from coming into the country. Immigration is a net positive for the United States, and those kinds of backwards and reactionary policies will damage the country’s economy. Many experts point to Japan as a country whose immigration policy has hurt its economy. Do you think that’s a fair comparison?

I would say that there is nothing that we Americans can learn from Japan with regards to immigration policy. Instead, as you say, immigration involves pluses and minuses. Each country has to come to its own weighing of those pluses and minuses. Japan and Australia have taken opposite views about that.

In Japan, homogeneity of the population and shared values are big economic sacrifices. Their national identity through their homogeneity is so important that the Japanese are willing to suffer all the losses they experience by not having immigrants. Australia has paid immigrants to come in, and within recent decades has changed its immigration policies to accept immigrants from all over the world.

In the case of the United States, we are at the opposite extreme from Japan. We’re a country based on diversity. The United States has accepted immigrants from all over the world. There is nothing we can learn from Japan except that the Japanese have a different point of view which is undoubtedly not the American point of view.

What do we get out of immigrants? We have skilled immigrants and, so-called unskilled immigrants. The United States has the highest percentage of skilled immigrants of any country. A measure of that is that among American Nobel Prize winners, the majority are either first-generation immigrants or the children of first-generation immigrants. That is because to win the Nobel prize, you have to be bold, you have to take risks, you have to be young and healthy, you have to do things that other people lack the courage to do. Well, that’s also what it takes to be an immigrant.

As for what we get from our unskilled immigrants: Here in Los Angeles, the construction crews are Spanish-speaking people from south of the border. The taxi drivers in Washington, D.C., the last time that I was there, were mostly Ethiopian or Somali. The taxi drivers in Los Angeles are now mostly from the Middle East. The United States gets good use out of our skilled immigrants and our unskilled immigrants.

What are your concerns about globalization?

Globalization is a fact. There’s very little that we can do to control it. Definitions are important. Globalization includes increased communication. Globalization also means more movement of people around the world from poor countries to rich countries. That is actually a dynamic that we can do something about. There would be less incentive for people to leave poor countries if we made poor countries richer. For a small amount of money, one can make big improvement in the economies of poor countries, and that then means less drive for immigration. It also means more satisfaction and therefore less support for terrorists. Those are things that we can actually do about the aspects of globalization that are of concern in the United States and the West.

Why is your work so controversial in some circles? Your scholarship is highly respected by some while being hated by others — to the point where you sometimes need to have security at your talks.

Among academics, particularly left-wing anthropologists, there are those who hate me. There are two reasons. One is jealousy. My books are successful. They do not write successful books because they don’t try to — and if they try to, they don’t know how to write successful books. So that’s one piece of it. A second reason that some academics dislike my books is that they equate geography with what is called “geographic determinism.” That is not something that I argue for. Instead, they misread my work or because they haven’t actually read “Guns, Germs and Steel,” these critics think that mentioning geography means geographic determinism. Geography determines some things we do and not others. Those are the two main reasons why a vocal minority of people hate my work.

One of the dominant narratives at present is that the United States is in decline and that this is the true end of the American century. In this reading of history, the future belongs to China. Do you agree with that argument and conclusion?

Such a narrative is complete nonsense. The United States is not in decline. The only thing that could cause the United States to decline would be the bad policies of the United States. There is no way that China is going to catch up with the United States unless we ruin ourselves.

What advice would you give to America’s leaders to help them make good decisions that sustain the country’s dominant position?

Ruining ourselves is something the United States is doing now in four ways. One is political polarization. A second is restrictions on voting, because democracy is a good thing. Democracy is, as Winston Churchill said, “the worst form of government except for all others that have been tried.” With restrictions on voting, we are undermining our democracy. We have reduced socioeconomic mobility in America so that it is now lower than in any other major democracy. We are reducing government investment for the public good. Those four things are the ways in which we are undermining ourselves as a country right now. All America has to do to stay on top of the world is to stop doing those four things.