When Donald Trump used the latest gun massacre to urge support for his pet project — clamping down on migration — no one could be surprised. His path to the presidency, like his time in office, is paved with anti-migrant fear-mongering. Already his re-election campaign has embraced the specter of a migrant invasion, and at a campaign rally, he entertained fantasies about shooting migrants. Clearly, President Donald Trump is driving the U.S. toward a new low. But disturbing as it is, in tying immigration law reform to domestic terrorism, he is not carving a new path. A quarter-century ago, the U.S. lived through a different national tragedy only to see migrants demonized and laws harshened.

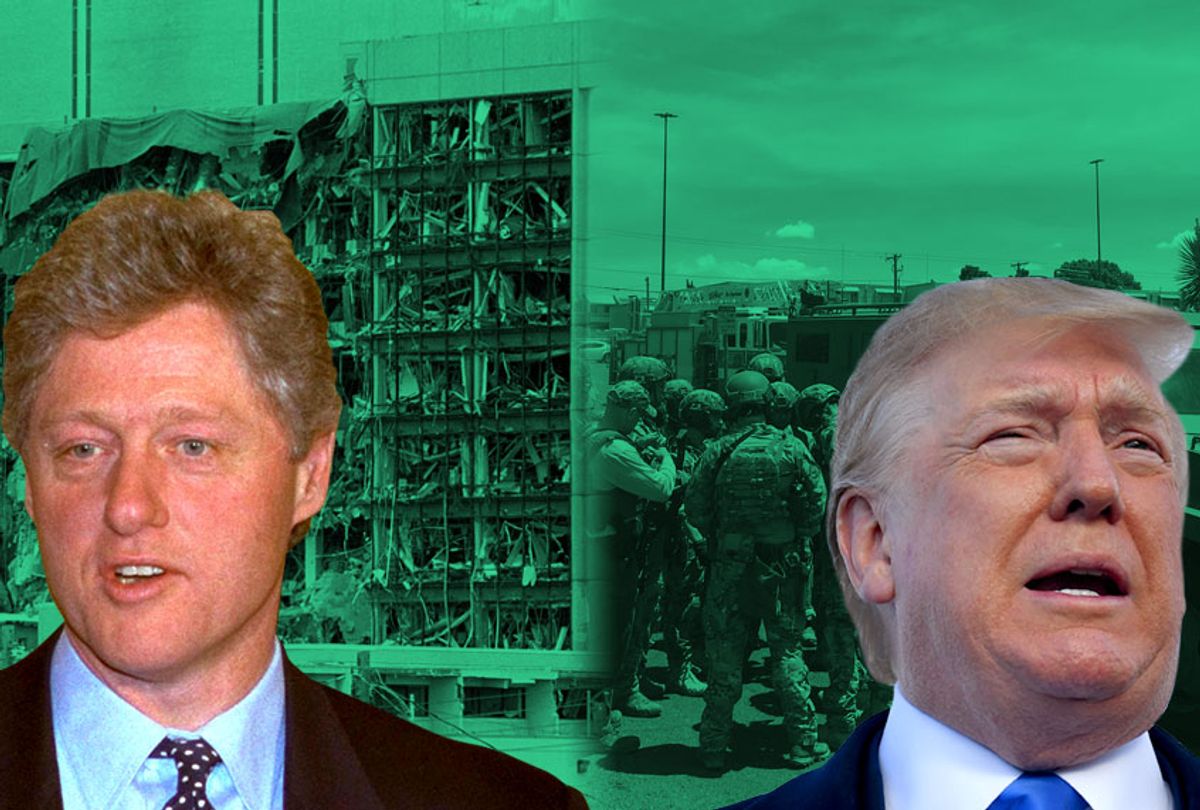

In April 1995, the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City cratered into itself as a fertilizer-fueled bomb blasted through the building. Nineteen children died — 168 people in all. Timothy McVeigh, a white, male U.S. citizen and Army veteran, was later convicted of the mass murder. McVeigh was executed, but his co-conspirator Terry Nichols remains in federal prison.

In the coming months, Congress would react by debating and enacting legislation sold as crucial to the nation’s mood to prevent terrorist attacks. Just over a year after the Oklahoma City attack, a Republican Congress presented Democratic President Bill Clinton with a massive, bipartisan bill, the Anti-Terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act. AEDPA limited appeal options and expanded penalties for terrorism-related activities. When he signed the bill into law, President Clinton described it as “a comprehensive approach to fighting terrorism both at home and abroad.” In public remarks from the South Lawn of the White House, Clinton praised “Democrats and Republicans, Republicans and Democrats, people who love their country as patriots.”

But overlooked in the fanfare was AEDPA’s enormous impact on immigration law. The law overhauled the power that immigration officials had to incarcerate and deport migrants. Before then, agents with the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) — the predecessor to today’s Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency — were required to detain migrants convicted of an aggravated felony, a catch-all phrase that also results in almost-certain deportation. After AEDPA, the INS had no choice but to lock up all migrants convicted of any drug offense. Through AEDPA, Congress also added to the list of crimes defined as an aggravated felony. Since then, gambling, some types of passport fraud, perjury and failure to appear for a court hearing have all received this harsh designation.

Not content with making it easier to land in an immigration prison and be deported, Congress also used AEDPA to limit longstanding relief from removal. Since 1917, immigration officials had been able to weigh the positive aspects of a migrant’s life against criminal conduct. Thanks to AEDPA, immigration judges saw that power severely curtailed. A few months later, another law, the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act, would repeal this power entirely.

Clinton’s decision to sign these two pieces of legislation in 1996 was certainly a turning point in the criminalization of migrants, but the political pressure leading to this moment had been brewing for several years. In the tough-on-crime politics of the 1990s, Democrats and Republicans clamored to prove how hard they could be on migrants. In 1994, Justice Department lawyer Ron Klain sent a memo to Clinton’s attorney general, Janet Reno, warning about brewing Republican efforts to make Democrats look soft on crime. Among the various downsides, he noted approvingly that “we generally support” the Republicans’ expected deportation provisions.

A year later, Democrat Chuck Schumer, at the time a member of the House of Representatives, explained his willingness to go along with harsh penalties for migrants suspected of aligning with terrorists. “Noncitizens do not—and, in my judgment, should not—have the same rights as citizens,” he said at a congressional hearing.

It is easy to distinguish between U.S. citizens and everyone else. Following the formal language of immigration law, Trump talks about “aliens.” These days, Democrats tend to talk about welcoming migrants. But in law and policy, both parties continue to lean heavily on the flexibility that Congress gave immigration officials to imprison and deport migrants. Former Democratic President Obama locked up more migrants than ever. Trump seems intent to surpass him.

In the rush to reject Trump’s latest anti-migrant screed, it is easy to overlook this history. But it is unwise to do so. In the mid-1990s, legislators from both major political parties proved willing to tie migrants to crime, then use an act of domestic terrorism to legislate immigration imprisonment and deportation. Almost a quarter-century later, migrants and their families continue to suffer. This time, let us avoid tarring migrants with others’ sins.

Shares