Vaginas are organs that are as misunderstood as they are obsessed over. Women are encouraged to fret constantly about the state of their vaginas and vulvas, which are supposedly never clean or trim enough, and purchase expensive treatments — like vaginal steaming — in a desperate bid to make their sexual organs more acceptable.

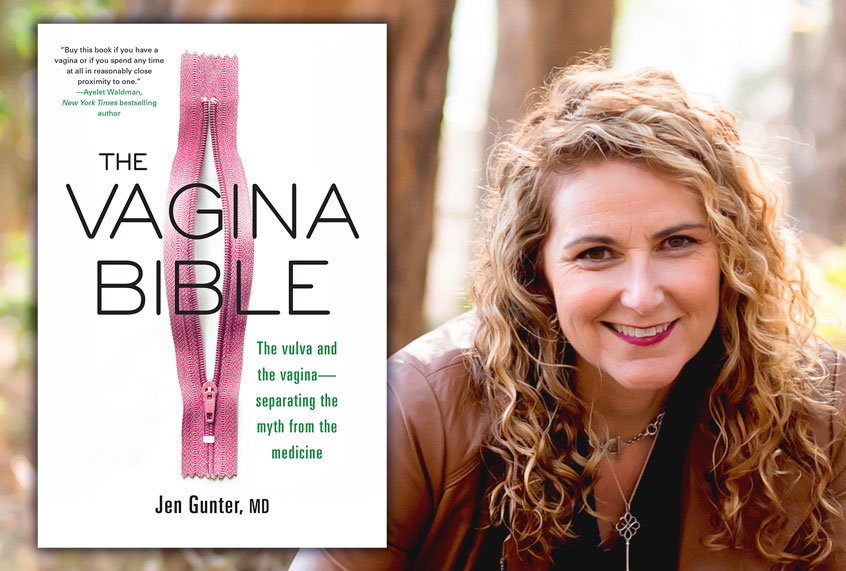

Dr. Jen Gunter, an OB-GYN with a specialty in pain management, is here to save women from vaginal anxiety. Her new book, “The Vagina Bible: The Vulva and the Vagina — Separating the Myth from the Medicine,” is the culmination of Gunter’s years of work as an online gadfly, debunking the “lifestyle” industry’s attempts to use women’s shame about their organs to sell them dangerous and unnecessary products meant to clean and tighten vaginas.

But her book does more than debunk myths. Gunter is here to offer all sorts of information about vaginal health care, from what to expect in childbirth to what kind of underwear to wear to trans-specific concerns regarding genital health care. She spoke with Salon about her book and about how to best care for any vaginas you might be carrying on your body.

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

Tell me a little bit about your journey towards being a vagina guru, calming fears and dispelling myths about vaginas.

After medical school, I was pretty sure I wanted to do OB-GYN — mostly out of a place of anger, which seems to be how I get to many things. But I was just annoyed that everybody [in the field] seemed to be a man. Not that any of them were creepy or mean or weird. It just seemed [like] such an obvious discrepancy, the lack of women in the field.

And then after residency, I did a fellowship in infectious diseases, which encompasses a lot of vaginal health issues, so vaginal infections, vulva infections. So I’d basically been running a clinic for vaginal and vulvar problems specifically, problems other gynecologists can’t fix, since 1995. So this is really my area of expertise.

When I decided that I wanted to try to clean up my little corner of the internet — which is a kind of a naïve thought, because I didn’t know anything about the internet at the time — I thought well, I should start with where I’m an expert. So that’s what I did.

When you say clean up your corner of the internet, was it just that you were seeing a lot of misinformation out there that you felt like needed to be countered?

I guess the origin story of me being online started with the birth of my kids and the death of my son. My children were so ill, because of their premature delivery. My son also had a heart defect, and my other son has cerebral palsy. And so I was just like everybody else at three in the morning, thinking like what the hell is going on and I need to learn more.

And I was really aghast at how bad the information was. Then I started thinking, wow, if there’s all this misinformation out there about prematurity, what’s out there in my field? Because I’d never really looked. I mean, I’d listened to patients with what they brought in, but I’d never really taken a deep dive. And now here we are.

What would you say is the vagina myth you feel like you have to spend most of your time or energy debunking?

That the reproductive track is dirty and full of toxins. This is a core belief of the patriarchy and it’s been around since, I believe, humanity has been around.

This idea that menstrual blood is dirty, that vaginas are dirty, is really…. That’s how we exclude women from religious services. That’s how we keep women in period poverty. That’s how we keep women from working. If there’s a biological way that you can identify a part of the population you can oppress, it’s a pretty effective tool.

We still see that belief today. People are talking about like vaginal steaming, as if the uterus is filled with toxins and you need to clean it. Somehow that’s been rebranded feminist, and of course it’s not. It’s the exact opposite. I mean, it’s faux feminism.

Let’s talk about underwear. A lot of women are warned that wearing some kinds of sexy underwear like thongs or are made of fabrics like nylon is dangerous. What’s the truth about that? Are we all doomed to wear white cotton panties for the rest of our lives?

Nope. I wear the sexiest, the lacy. I love fancy underwear. It’s such a patriarchal myth.

I remember hearing that in medical school and putting my hand up saying, “So if white cotton underwear is important for skin health, why do we not all wear white cotton clothes all over our whole body? That makes no sense to just target the vulva.”

Of course, I got a sour look. But it’s a purity myth, these ideas. It’s bad girls are loose and wear lace and black thongs, and good girls wear white cotton granny panties. That would be what my mother would say, and certainly how I was raised.

What about toxic shock syndrome? I know that when I was young and first starting to wear tampons, that scared the crap out of me. A lot of people are afraid of that happening. How worried should we be about it?

We know now that menstrual toxic shock syndrome happens to about one per 100,000 women of reproductive age per year. Women do many more things every day that are dangerous. That’s why I really believe in the power of informed consent. You give people the information and then they can make an educated decision about their body. There is a risk, and it’s one of those extremely low probability, high consequence things.

It’s about the same risk of getting struck by lightning, but we don’t tell women that they shouldn’t leave their homes so they don’t get struck by lightning. We say, “Well, here’s the information and this is what you should know and this is how you can best protect yourself.” You’re probably far more likely to die in an accident crossing the street, but we don’t tell women not to cross the street. We say, “Here is the information that you need to have to make an educated decision about the best way to cross the street.”

Fear sells, and so I think that sometimes the messages, the facts people need, gets lost.

One of the things I was impressed by in this book is that you have a section about medical concerns for trans patients, both trans men and women. What are some of the things that you feel people should know about medical care for trans patients when it comes to vaginal care?

Well, first of all, that healthcare is healthcare. I hoped by including it, I was making that statement, that every single person deserves the healthcare that they need. And that’s why I really wanted it up front in the book too, to make that statement.

There’s already layers of misinformation when you’re talking about the vagina. And there are societal ideas and there’s horrible religious doctors and there’s Catholic health networks and there’s all these things that can oppress you.

But then imagine that you’re trans, and you have that other layer of oppression and hatred and all these things that shouldn’t happen. I wanted everybody to know how much harder it is for people who are trans to get the care they need, and that there are a lot of concerns that can sometimes be addressed, especially early on. Everybody should be getting their HPV vaccine early. People who are considering transition, they want to know about a lot of this information beforehand.

Obviously, for someone who’s already had gender-affirming surgery or is far along, this might be basic information for them. But I also know that a lot of OB-GYNs are going to read my book, and I know a lot of trans people have to educate their doctors on vaginal health concerns, which kind of sucks to have to tell your doctor what you need. And so I’m kind of hoping too that I can help bring medical professionals up knowledge-wise as well.

This is more a vagina book and not a uterus book, which I think readers need to know going in.

This is really a book about like the parts, like, “this is the vagina, this is the vulva, here’s what happens to them.” Now obviously, I write about sex, because many people use their vaginas for that. I also wanted people to know how pregnancy and childbirth might have an impact or what they would need to know vaginally.

We think of pregnancy as all about the uterus, but you say that a lot of women are surprised by the magnitude of the changes to their bodies. What changes to the vaginas tend to surprise women the most, and what should they — pardon the pun — gird their loins for when they decide to have a baby?

There’s this idea that you’re going to have a baby and, six weeks later, you’re going to be dying to have sex again and your libido is going to come back. But the physical changes, never mind the being-up at night, have a dramatic impact for a lot of people. And that’s okay, just to understand that.

I think that many women are just unaware how uncomfortable it may feel for a period of time. But if you think about, if you have a C section, it’s so weird that we’re all, everybody says, “Oh yeah, like I had my belly cut open, so of course it’s going to feel weird for a few months.” So I’m always like, if you’re delivering a baby, then there’s going to be changes.

The other thing, though, is that there should also be a period of time where everything’s working pretty well, and if it’s not, then you need to be able to find a provider who’s going to help you.

I see a lot of women who are three years out from having a kid, and they still haven’t been able to have sex because of pain. And they waited three years, because everyone just kept telling them, well wait. If things aren’t better after like eight to 10 weeks, you need to be seen. So I wanted women to have that information that that they need to know when things might be going wrong that they need to speak up. And if the person’s not listening, then maybe I can give them the words to either get that person to listen or find someone who can.

You have a lot of good information in here about sex. I was particularly interested in the longstanding debate over whether there is a G spot, and whether stimulating it will cause women to squirt during orgasm. Where do you stand on this subject that has been debated for decades but never entirely resolved?

Well, there is no hidden gland in the vaginal tract canal that we don’t know about. I’ve taken many vaginas apart. I’ve operated on many vaginas, as have many other gynecologists. If there was a hidden gland, we would have found it. So I think that’s really important.

Nobody ever goes back to the original article written by Gräfenberg. I did. He was talking about an area that was clearly where the clitoris wraps around the urethra. The whole idea of the G-spot clearly comes from people who don’t understand how large and internal most of the clitoris is.

This clitoral erectile tissue in this location — [which] somehow became some magical spot that you’re going to touch. So there is no “hidden” G spot. Definitely many women have areas that are very intimate with the undersurface or close to the urethra that are very sensitive with the right stimulation, because there’s a lot of clitoral erectile tissue there.

As for squirting, there is no gland that can produce large amounts of fluid. It doesn’t exist. And as I mention in the book, the prostate, which is pretty good size, is the size of a walnut, that only produces a few milliliters. So these videos of large amounts of fluid coming out are clearly manipulated in some way. The data that we have tells us that women who report squirting, I’m talking about large amounts, it’s probably urine. And that’s what the studies tell us.

That doesn’t mean that they’re not having a stronger orgasm. Maybe they’re getting such strong pelvic floor contractions that they’re emptying the bladder. It’s just not some hidden secret gland. It’s urine.

It seems to me that a lot of the reason that debate is fraught is because, on one side, there’s people that feel like they’re being attacked for having sexual experiences that correlate with this idea of the G spot. And on the other hand, people, a lot of women feel like it’s being used as an excuse for men to make everything about the vagina and not the clitoris.

Facts are the most important thing, to know what’s going on factually. But I would also say don’t get hung up with metrics. So like, did you squirt, did you not? Who cares?

I want that information to be there, because women will say, “Well, my partner thinks there’s something wrong with me because I can’t squirt.”

It’s always a male partner. I’ve never once had a woman who partners with a woman cry in my office about what she’d been told. I’m not saying it doesn’t happen, but I think that that there’s a unique way that some male partners talk to women.

Stop worrying about metrics. Does it feel good? Is what you’re doing feeling good? Is it pleasurable? Great. You know, who cares if what comes out of your body is urine? Sex is supposed to be wet and messy and glorious and sticky. Focus on the pleasure. And I’m hoping some of the facts in the book might help explain those pleasurable experiences. But it’s not a competition. It’s about how good it feels and are you getting stimulated in the way that you need to be stimulated?

Speaking of partner pressure, you have a chapter in the book about women getting plastic surgery, billed as “rejuvenation” on their vaginas, presumably to make them more aesthetically pleasing or “tighter” or all these other ideas about what a vagina should be. How do you feel about these kinds of plastic surgeries?

Well, I think that they’re offered in a very predatory fashion. I see 20, 21-year-old girls who’ve never even had sex thinking they should have their labias made smaller.

People should know that your labia minora is a sexually responsive organ, so making that smaller is like making a penis smaller. And in what world would we say a man should do that?

It’s not just about cosmetics. If getting a nose job made your sense of smell worse, had a potential for a serious negative, long-lasting impact on your sense of smell, and that was unstudied, you would want to know that information before you consented to it, right?

There’s plastic surgeons that advertise that [to] women because they should look sleeker in their yoga pants. Then we see articles glorifying rock gods in their tight pants [that] you can see their penis and balls through. Why do we glorify male genitalia and we say that female genitalia should be smaller?

People need to understand those pressures and that 50% of women have labia minora that are longer than their labia majora. 50%. Vulvas come in all shapes and sizes, and so to say that there is an anatomic standard is really incorrect, just like it’s not wrong to be four foot nine or six foot three.

And this idea that vaginas should always be tighter is a very patriarchal ideal. Cultures for thousands of years have been promoting vaginal astringents to tighten the vagina. Why does the vagina have to make up for the shortcomings of the penis?

If there was one thing you want people to understand about vaginas, whether they have a vagina or they don’t have a vagina, what would it be?

Know that it’s a body part like any other body part, and vulvas and vaginas come in many shapes and sizes. Any decision that you want to make with your vulva and vagina, just get the facts. And if you have the facts and you still want to make the decision you are going to make, be it plastic surgery or whatever move you’re planning, it’s your body and it’s your choice, but make an informed choice so you know what you’re doing.

And also, don’t confuse the vagina for the vulva. They’re different organs.