Liz Phair, as a young indie rock musician in the '90s, got a lot of attention right out of the gate with her first album "Exile in Guyville", due to the frank, sexual nature of the lyrics. But the frankness that allowed the album to persist as a classic was not in the dirty words, but in the blunt emotional truths Phair examined, truths that were particularly welcome to a female audience who was not used to their secret stories being so boldly told.

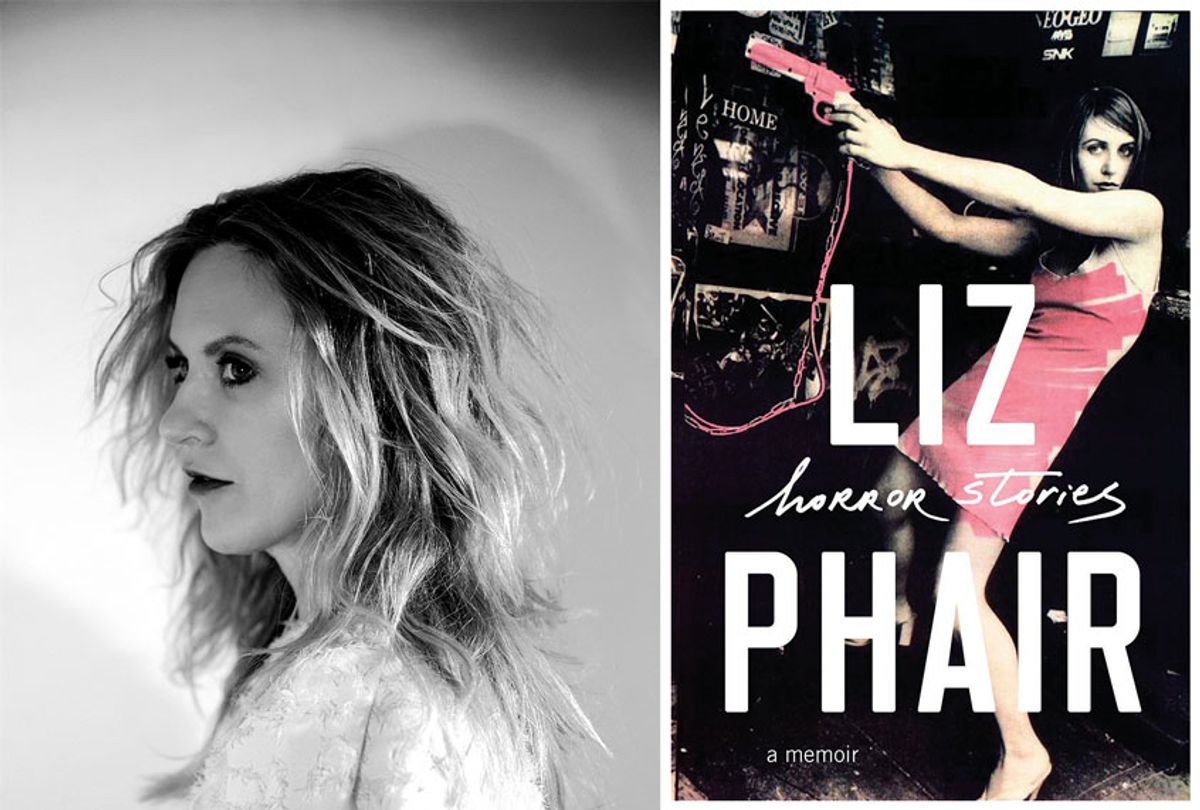

Phair brings that unsettling sense of candor to her first book, a memoir titled "Horror Stories," released on Oct. 8. In this book, Phair chronicles the various kinds of violence, emotional and otherwise, human beings can do to each other by exploring stories drawn from her own life. It's often hard reading, but vintage Phair, the sort that long-time fans will be expecting. Salon's Amanda Marcotte spoke to Phair about her book and the darkness that lurks behind so much of ordinary life.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

The book is called "Horror Stories." The title doesn't disappoint. This isn't a traditional memoir so much as a series of vignettes that illustrate these small horrors and shames and uglinesses and power trips of life, your life, but I think most of us can relate. Why did you decide to focus on on this concept of horror?

It was spurred just by feeling a lot of horror, in 2016 and 2015, watching what was going on politically in the country. At the same time, coincidentally, some of the most influential music icons, for me, were dying in a quick succession. I just remember feeling this kind of weightiness for the culture, and feeling like every day that I stared at the television and tried to grapple with what was happening.

It wasn't just who won the election. It was also about what we believe in and what our values are, and feeling like the rug had been pulled out from under us.

The title is a little tongue in cheek because of the big entertainment horror industry. I wanted to point out that horror stories really are more private personal events a lot of the time.

These stories are really not about these big ugly values questions that we're having, at least not on the surface, in our our culture. They're more about the kind of small, callous ways we can treat each other. What is that about human beings? Why are we like that? Why do we fail so often to be our better selves, just in the way we relate to each other?

Right? How can we have a character and a personality that we believe in and count on and we act outside of that?

I think it has to do with evolution. The social culture moves faster than evolution does, so we're stuck with a lot of instincts that are at war with intellectual beliefs. Now that we all live in a society, which historically or evolutionarily speaking is just a brief amount of time, our instincts and our fight-and-flight responses or just impulsiveness or greed, all those things are instinctual and they fight with our consciousness.

I don't know. I think about it a lot.

I guess it's the great unknowable. Right? It's something that you get close to but never have a certain answer.

It reminds me of that paradox where you step halfway towards the wall and then you step half of that step and half of that step, and you never actually reach the wall.

You mentioned how 2015, 2016 was a horrible year of deaths. Obviously, David Bowie was a big death for a lot of people, but the one that I think was very affecting, that you mentioned in the book, and I related to strongly because it threw me for loop too, was Prince's death. Why do you think his death, in particular, was such a gut punch?

I think because he lived a lot of his professional life shrouded in mystery. I think we had this strange relationship with Prince because he had a strange relationship with his own public persona. He was both larger than life and also incredibly shy and private.

It felt like the freest among us were being taken down right at the same time that our own freedoms were in jeopardy. That's the way I rationalized it. I don't know if that's true for everyone.

That's a really very evocative way of putting it. I want to be clear, though, to the readers that this book is not unrelenting horror. I think you really counterweigh the uncanny with moments of kindness and beauty and humanity. How did you find the right way to balance the soothing versus the unsettling?

Honestly, I think that's how I try to live. There's only so much that I could stick my head into the rain water barrel and hold it underwater for a while to think about this stuff. I have to come up gasping for air and get some sunshine and dry out.

Life has taught me that you can't just wait for life itself to balance everything out. Bad times will follow good, and good times will follow bad, but I find it a major survival advantage to try to balance your own light and darkness.

I think it's a huge mistake to never look at the things that trouble you and to never revisit the things you feel guilty about. I think that's a tremendous mistake. Should you wallow in it? No.

One of the reasons I wanted to write this book is because these are the stories that got stuck in my loop. I just kept replaying them. To what end? I just almost tortured myself with them. Writing through it allowed me to decide what I thought, and to pass judgment on the whole episode.

I found that I had more compassion for myself than I would've thought, considering how long I've been chewing on these gristles.

You describe eloquently how shame, in particular, is this feeling that you just carry around with you as a weight for the rest of your life. All the people you've failed, even the animals, they come back and haunt you when you're least expecting it. Why do you think shame, of all emotions, has that kind of power over us?

Shame is incapacitating, one of the few things that stops you from acting, which is weird. Shame, just suddenly you shrink up.

This is a roundabout way of answering the question. I was shocked at my own writing, looking at how many chapters dealt with Christianity and morality framed in a religious perspective, because I am not and haven't been for decades overtly religious in any way. I don't go to church. I don't, other than a sort of cultural way, observe the holidays. I have a private belief in God, but there's so much in my stories that must be in my psyche about religion and right and wrong and God and the devil. The only thing I can think about shame is that it comes very early. I think it's a very early and very surprising emotion that we get a little traumatized from.

It's interesting that you mention Christianity because I was also struck by your references in this book to paganism. What does paganism mean to you, in the context of thinking about religious themes?

I'm one of those people that believe the Earth is alive and that we are on a being, a living being, and all of nature is an extension of this worship-worthy being that we're a part of, that we're an extension of. I just see nature is very alive and interactive in a way that is spurred on by an overactive imagination, but I think is based in scientific facts.

It is not acknowledged as much as it should be. I don't know if it was at one point, and we lost it. Maybe I'm just nostalgic for a time when we cared more about our animalness and our naturalness.

Have been following the kids having these climate strikes around the world?

I have been fascinated by Greta Thunberg. I see in her eyes the way my mind works, which is she's really looking all the way out, if you telescope it back, toward the little-conceived of truth that if we disrupt our system, that systems can behave unpredictably once they're disrupted.

A system can slip. A system can pull out of balance unexpectedly. It's terrifying. It's such a big thing to conceive of. Most people lack the capacity to envision what I think she sees very clearly. She doesn't understand why we're all walking around like, "La, da, da, da."

It's an overwhelming and very real threat. I think people have trouble processing that, when they're already putting out little fires in their personal life, let alone at work. We're relatively small creatures with an overactive brain. It's really hard to focus on the most pressing issue of our day, especially with media and advertising keeping our eyes glued and our concerns anchored to what they can sell us.

It's interesting that you drew a connection between yourself and Greta, because I think going all the way back to "Exile in Guyville," your work, and this book especially, is so much about saying the thing that other people won't say. I remember when that album came out, people treated it like titillation, but fans, and especially your female fans, saw it more as telling hard truths. What is it that helps you look the ugliness in the eye?

I think I felt, so much, like the truth was of such serious value to me I think that's because of being lied to and being required to lie. That "emperor has no clothes" feeling happened to me a lot when I was young. I felt like I was not supposed to speak about or acknowledge that things were going on that just happened through a matter of living and doing all the things that we do.

If everyone were like me, we probably wouldn't have a society. I'm not sure I'm of much value, other than to observe things and be able to encapsulate them in a way so that I can convey it to you. You can open it up and see, smell, feel, experience it. That's my talent. That's what I've always done. I just have always felt like,however hard and painful the truth was, it always was more constructive. A lie just sort of tripped you up and stopped you from progressing.

There's a lot in this book about bodies and and looks and how we think about them changing. Everything from putting on makeup to heavier topics like disfigurement, injury, what pregnancy does to people's bodies. Why does this topic hold so much fascination for you?

I'm very physical. For being such a dreamer, I'm very grounded in my body and physicality. To my utter shame, I really laugh at physical humor. I'll be the first person to just spit laugh at the television when something really dumb happens, when it's physical. I think about my body. I think about other people's bodies a lot. Maybe it's because my dad was a doctor? That's possible. I think it was really just the way I'm wired.

My identity extends into my body to an unusual degree. Good and bad. It's actually not that bad, really. I can't think of that many bad things about it.

I think it's bizarre, the way that our society often treats the mind and body as somehow separate things. They're clearly not.

Some people live like that, though. I'm always fascinated by people that consider their body a vehicle to get their brain around. I don't understand that.

I feel like folks like that, they're going to feel old age more severely, unfortunately, because it sneaks up on you.

That's true. Because they won't be ready for it and then all of a sudden they'll be like, why is my arm falling on the ground there?

Having written this book, do you think you got a bug for writing? Do you want to write more?

I had that bug awhile ago. I was trying to write fiction before I wrote "Horror Stories." I'm still going to try to write fiction. Once I learned how difficult it truly is to write successful fiction, I had to stop and fall apart and give it up for a second.

It amazes me. I always loved reading. I always loved literature. I just had no idea what went into creating successful imaginary worlds. I definitely have the bug for writing. I am praying that people like this book enough that I can continue writing, because it's really satisfying.

Once I broke the long form, I felt like I was making songs, but they were stories. It was the same, a very comfortable, very familiar, and very happy impulse and creative energy.

Shares