Our country needs a new republican party that adopts the mission and the determined statesmanship of the original Republican Party. If a primary purpose of studying historical writing is to meditate upon past greatness for our present instruction, then we ought to repair to our studies of the leaders of the old party. They were the worthy descendants of their republican forefathers and more worthy of our emulation today than anyone else in our country’s history. But Americans today, and even scholars, have forgotten the breadth of their achievement.

That old party opposed and subsequently banished slavery from the United States, and slavery is here no more. But the emancipation of the slave for the sake of the slave comprised part, not the whole of their mission. From the party’s inception, the intended beneficiary of their great deed was all of us, including enslaved African-Americans. The spread of slavery threatened to expand the number of its immediate victims but also threatened to reduce everyone else to political vassalage, ruled by the slaveholders and their adjunct classes. The mission of the party, said the platform of the first chapter in Michigan in 1854, was to defeat an “aristocracy, the most revolting and oppressive with which the earth was ever cursed, or man debased.” Their new organization recognized “the necessity of battling for the first principles of republican government.” Other state platforms and the leaders of the party avowed that same mission. That is why they took the name “Republican.”

The founders of the Republican Party knew what the founders of the republic knew, that slavery and American republicanism could not peacefully coexist. One or the other was marked for death. In his notes for his essays in the National Gazette, James Madison recognized that notwithstanding the republican form of constitutions, wherever slavery prevailed, actual republican government was impossible. Because slavery concentrated ruling power in the slaveholding class, “All the antient popular governments, were for this reason aristocracies.” Noting the same effect in the South, he concluded, “The Southern States of America, are on the same principle aristocracies.” The success of the ambitious republican project launched in 1776 would depend upon the elimination of slavery.

From Maine to New Jersey, and from Massachusetts to Minnesota, slavery was abolished or prohibited. But it burst its confinement in the southeastern United States, spreading directly to the west. Oligarchic rule by the few for the advantage of the few grew with slavery and matured in the antebellum South.

The economics of slavery prepared the ground for the political establishment of oligarchy. Slavery was an engine that generated wealth inequality, enriching the few but impoverishing general society. The profitability of slaveholding and landholding to the owner biased the reinvestment of profits back toward the purchase of more slaves and choice lands, bidding up prices. Although the raw numbers of slaves expanded from 1790-1860, slaveholding and landholding concentrated in proportionately fewer hands because the already-rich could successfully bid for those investments and become richer. The slaveholder who could not keep up exited the slaveholding and landholding business. In close proximity to slavery, the non-slaveholder became poorer because profits from slavery were reinvested in slave labor rather than in wages paid to free labor. Therefore, the non-slaveholder could not form capital from wages and become a proprietor himself.

In contrast, economic mobility thrived in the republican North. Laborers formed capital from saved wages and became proprietors. Middling farms in the 20-acre range dominated Northern landscapes in all the free states. The high cost of wage labor biased investment towards labor-saving innovation, creating new value, new industries, and new jobs. Wealth diffused under conditions of liberty, and even if a laborer never achieved middling wealth, his political equality was secure.

But in the antebellum South, relative wealth determined relative rank in political society. Accustomed to command the labor that they owned by legal title, the rich established their title to rule over all society by a common set of political devices. Many of their states enumerated slaves, the most important form of wealth, in the apportionment of representation in their state legislatures. Some maintained property qualifications for voting or holding office, which became a fixed political distinction because economic immobility was mostly fixed. The slaves and a class of nominally free Americans filled out the ranks of the ruled classes.

The oligarchy ruled the South for their own advantage. They authorized projects that primarily benefited themselves but exacted the costs from the whole of society. In Virginia they exempted a large share of their slaves from taxation, but used tax revenues to fund slave patrols, protecting the interest of their ruling class only. In Georgia, they used public funds to pay for railroad branches that served the planter-dominated Black Belt and resisted the establishment of branches elsewhere. In all the slave states, they funded universities and academies for the wealthy but blocked the establishment of common schools.

When the local governments of the predominantly non-slaveholding districts in Spartanburg and Greenville, South Carolina, wished to tax themselves and fund common schools, the state legislature forbade them. Why? Because as one member of the South Carolina oligarchy explained, “Certain menial occupations are incompatible with mental cultivation.” And another forthrightly blamed the misbegotten demand for common schools on “universal suffrage” and its moral basis, the principles of the Declaration of Independence. He countered, “We deny that all men are created equal … We deny that any human creature has any unalienable rights.”

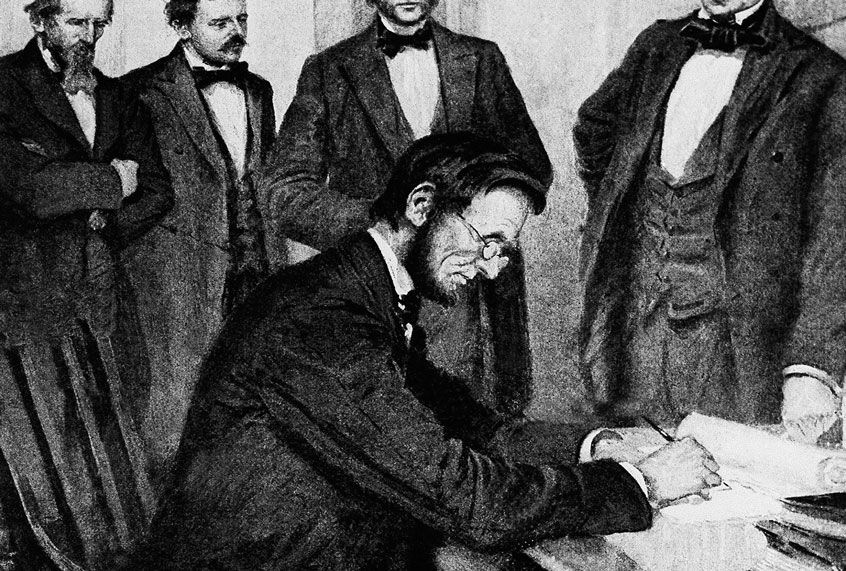

But to Abraham Lincoln, these principles were “the sheet anchor of American republicanism.” And because, education reformer Calvin Stowe wrote, “republicanism can be maintained only by universal intelligence,” its preservation required “the education of our whole people.” The practices and principles of Northern republicans accorded with this view, standing in sharp contrast to the practices and principles of Southern oligarchy.

Among all, and not only among slaves and free black Americans, rights in the South were not fixed according to the immutable standard of natural equality, or even according to the national standard erected in our Constitution. Republican James Ashley of Ohio observed that in the South, “The guaranties of the national Constitution, so far as they affect the individual rights of an American citizen, are denied alike to all men who are not of this privileged class.” That was because rights were mutable social constructs, distributed according to rank. Hence, rights depended upon successful struggle for mastery. The necessity and uncertain outcome of struggle best explains scholarly findings that show the high murder rates in the antebellum South. You affirmed your rights by establishing dominance through individual struggle.

The oligarchy restricted freedom of speech and assembly in the South and adopted special measures to prevent abolitionist speech and literature. They attached fearful penalties to their anti-abolitionist laws, knowing all too well that slavery was the foundation of their wealth and power and was their Achilles’ heel. But the oligarchy did not deny and in fact openly boasted of their repudiation of republican liberty. On the floor of the House of Representatives, George McDuffie of South Carolina mocked majority rule as “King Numbers.”

This was the tyrannical system that had once seemed to have reached its farthest extent westward by 1821. The Missouri Compromise line and the boundary with Mexico impeded its expansion northward and westward. But the oligarchy pushed slavery through those limits, too. The results of the Mexican War opened the Southwest to the expansion of slavery all the way to the Pacific. Then the repeal of the Missouri Compromise with the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854 opened the Northwest to slavery.

The year 1854 was a turning point. The possibility that America might become a slave nation ruled by a remorseless oligarchy was real. Sensing the coming demise of American republicanism for all time and backed by awakened citizens, Americans arose at once from all parts of the free states and discarded the banners of their political parties for a higher purpose.

When republics are healthy, political parties are interesting to citizens and boring to philosophers. Healthy republics are stable, resistant to transformation, entailing general party agreement about the republican form of the regime. Party disagreement is limited to government policy, a class of political concerns that does not call the fundamental form of government into question. Politics is happily mundane and lacks real drama. No reasonable citizen picks up a gun if the question at stake in political conflict is a few marginal points in a tariff or income tax rate. But if the stakes are whether we shall govern ourselves or shall be governed by self-appointed superiors, then it will be hard to contain civil strife.

After the repeal of the Missouri Compromise in 1854, our republic was desperately sick, unstable, and in danger of transformation. The policy differences that divided republicans into separate parties no longer mattered in light of approaching tyranny. Republican Representative George Julian of Indiana recollected that “tariff men and free traders, conservative Whigs and radical Democrats, Know-Nothings and anti-Know-Nothings, strict constructionists and Federalists” all dropped their policy differences and united in a new party devoted to the defense of the political regime established in 1776. In their first national platform, they invoked “our republican fathers” and reaffirmed the self-evident truths of the Declaration of Independence. Their party’s banner was the banner of the American Revolution, which they faithfully carried throughout the rest of the testy decade and then through war.

The rise of the Republican Party surprised the Southern oligarchy. For years the free states had appeased the demands of the oligarchy in order to preserve the Union, but those days of appeasement were now gone. The oligarchy soon learned that they had mistaken misguided patriotism and moderation for cowardice. When forcefully accused of revolutionary intent in Congress, Representative Eliakim Walton of Vermont turned the charge back on his accuser from Georgia. They were the revolutionaries, he said. As for the purpose of the newly formed Republican Party, he declared, “It is a counterrevolution that we have inaugurated; it is against that other revolution …; it is to roll over that other revolution, and to roll back the governments of the nation and the States to the principles and policy of our revolutionary fathers.”

One element of their statesmanship that sharply contrasts with the conduct of our political leaders today is their command of the principles of our government and their clarity about the dangers that our country faced in their public rhetoric. They excelled at clear explanation and calm debate, which served to teach the American people what their duty was. In debate the Southern oligarchy often threatened and sometimes executed violence, but the Republicans steadily maintained their composure and sustained their argument in full view of the American people.

Historians sometimes note that both North and South seized the mantle of the founding, and then pass over the question as to who were the true heirs of 1776, as if the question was and is indeterminate. The progress and termination of the conflict over these claims in the 1850s support a different conclusion and yield a lesson that we ought to heed today. When Southern statesmen hitched their cause to the republican fathers, Republicans responded with sustained blasts of quotations taken from the primary records of the founding era. By 1860 intelligent Southern statesmen were forced to admit that they had indeed broken from their fathers, or as Senator James Mason of Virginia quaintly explained, “the opinion once entertained, certainly in my own State … has undergone a change.” Referring the next year to the “common sentiment” of 1776, Alexander Stephens said, “Those ideas … were fundamentally wrong.” These admissions were forced from their lips by Republican statesmanship.

Their conviction and clear-eyed, public explanations were armed by their courage. They did not shrink from the immensity of their task. Due to the failed republican revolutions in Europe and the expansion of slavery in America, the progress of republicanism in the West in the first half of the 19th century stopped. The West was moving back to monarchy and aristocracy, the common and ancient condition of the rest of the world. A new Napoleon ruled the French. Aristocratic-monarchic Prussia had crushed the republican revolutionaries of Germany. British aristocracy was resurgent. A Hapsburg was placed on a throne in Mexico.

By 1861, the last stand of republicanism stretched from Canada to the Ohio River, from Maine to Minnesota, plus California and Oregon. Britain and France were poised to enter our American conflict in favor of a powerful new oligarchic regime in the American South. The Confederacy coveted expansion and was considering the reopening of the slave trade. But in republicanism’s final redoubt in the free North, the Republican Party emerged to defend what Lincoln called “the last best hope of earth.”

And they did roll back the oligarchic revolution and saved the cause of liberty in America and in the world. Certainly, the Republicans did not completely uproot the aberrant regime after the war. The stubborn influence of the Southern oligarchy survived defeat and meddled with American ideals and institutions well into the next century. Racism, or second-class citizenship on the basis of racial identity, is nothing more than oligarchic ranking by one of many possible methods. The persistence of this influence is a testament both to the great power of the antebellum regime and to the Republican courage that brought that power low.

With the Union victory, republicanism made gains abroad as well. After the war, General Philip Sheridan and a veteran army moved to the border of the Rio Grande and ran guns to Mexican republicans, assuring the success of Benito Juárez. The American victory also emboldened European republicans: Napoleon was cast down and a new French republic was raised, while the Second Reform Act of 1867 saved and improved republicanism in Great Britain.

Within the modern democracies, so-called, we might perceive that apostasy is again on the rise. But who can tell us where we are tending today? Whether a new ruling class is poised to tear down and replace our republic with a worse form of government? Who is now brave enough to uphold and defend republican principles?

Waiting to be summoned are many tens of millions of Americans whose hearts still warm to our old creed. Those millions are all sons and daughters of the builders of our temple to liberty, qualified as members of our republican family only by their affection for the first principles of our republic, not by ties of blood. If the case for republican counterrevolution can be made plain to them, some number will rally to its banner as they did in 1854. To raise that banner, disdainful of the hazard, defines the duty of a new or revivified republican party.