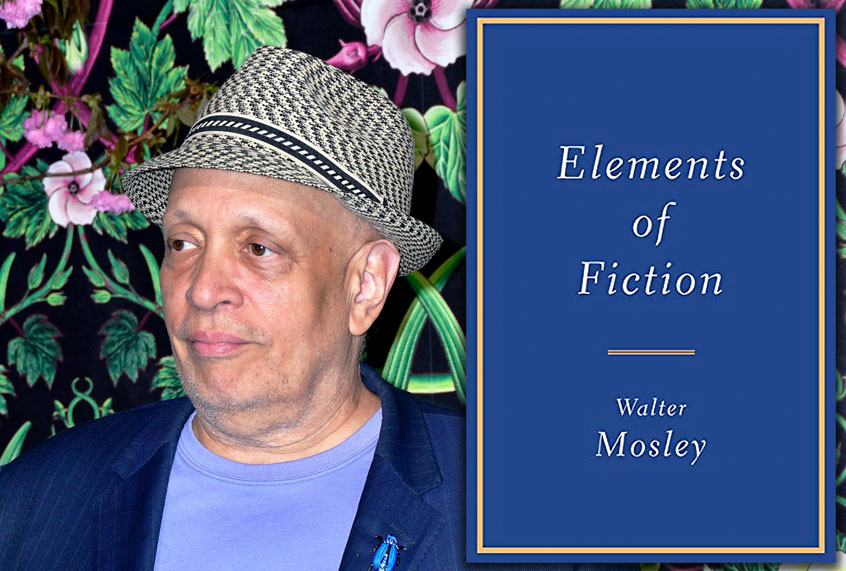

Walter Mosley is one of America’s greatest crime-fiction writers. He is the author of almost 50 books across multiple genres including the bestselling mystery series featuring detective Easy Rawlins. Mosley’s essays on politics and culture have appeared in many leading publications, most notably The New York Times Magazine and The Nation. In September the New York Times featured his widely read op-ed “Why I Quit the Writers’ Room”.

Mosley is also a writer and consulting producer on the FX period crime drama “Snowfall,” which recently wrapped its third season (Seasons 1 and 2 are currently streaming on Hulu) and has been renewed for a fourth.

He has also earned numerous awards including the PEN America’s Lifetime Achievement Award, a Grammy, and an O. Henry Award. His newest book is “Elements of Fiction,” a follow-up to his instructional book, “This Year You Write Your Novel” (2007).

In this wide-ranging conversation, Walter Mosley reflects on his relationship with the late John Singleton, the cultural impact of Singleton’s film “Boyz n the Hood,” and their collaboration on the TV Series “Snowfall.” Mosley also offers a critical perspective on the fantasies of Whiteness and the Age of Trump.

The following has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

What is your writing routine now? Are you still doing the three to four hours a day?

I never go to four. But yes, three hours in the morning. I actually find that most people write in the morning, anybody who’s been at it for a long time. I remember [late science fiction author] Octavia Butler would go home in the evening from work and go to sleep at eight and then wake up at four in the morning and write then. Some people I know write at night or they just write in spurts. But most people who write every day that I know do it in the morning.

I have been thinking a great deal about Octavia Butler in this moment that is the Age of Trump. Trump really is a character in one of her novels.

That’s funny. I like that. I think she would have liked that observation as well. Octavia was very wonderful. Octavia was incredibly confident in her knowledge, which was always wonderful. I had good times with her. We would just see each other all over the country while doing events.

Given your many accomplishments how do you balance confidence with hubris?

There’s a big difference between arrogance and hubris. Hubris is when you go out there and say, “I’m going to take the place of somebody really big or I’m going to be in a controlling situation.” With hubris, there are people who destroy themselves by thinking too highly of themselves. I don’t think about it because I don’t mind if somebody is confident in their work. Okay. You know you are. “I’m Walter and we’re all in this together.” I’m sure some people may think I’m arrogant. That is likely especially true if they don’t like my work. I know I’m a good writer.

As a writer and person who is creative for a living, how do you figure out how much to keep for yourself and how much to give to the public?

For some people, their public life is more important than their private interior lives. A lot of people love doing their art by itself. And there are other people, me included, who have a different set of priorities. I’m a writer and I love writing. It’s a great thing, but it doesn’t define me.

I did an interview with a very well-known screenplay writer, Walter Bernstein, on the occasion of his 100th birthday. Walter Bernstein, he wrote “The Front.” he wrote “Fail-Safe,” he wrote “The Molly Maguires.” He is a major writer. Bernstein was the first American to interview [Yugoslav communist revolutionary] Tito during World War II. He rode around Harlem with [boxer] Sugar Ray Robinson in his pink Cadillac and wrote an article about him. He marched with [entertainer and activist] Paul Robeson for years.

Bernstein was part of the group that kept Elia Kazan from getting the lifetime Oscar achievement award from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Science because he had “named names” during the Red Scare. Bernstein was blacklisted. He did LSD therapy in the late ’50s and early ’60s.

It wasn’t until my last question when I asked him about his films. Why? because Bernstein had lived an interesting life. As far as I’m concerned, living an interesting life is better than being good at your craft. If you start to define yourself by how other people define you then you are probably missing out on yourself.

How did reading comic books as a child inform your creative voice as an adult?

All writing, but fiction especially, must rise up beyond itself. Whatever we’re writing, whatever we’re doing, you have to cut it down. My hero Jack Kirby was a storyteller. He told the story in a frame. So you had to imagine from Frame 1 to Frame 2 what had happened, what had moved. You can actually see that in comic books. That alone allowed me to imagine telling stories. Unfortunately, I have yet to write a comic book.

How do you manage your creative voice across different styles?

There are two things in America we don’t have much time for now. Reading is rereading and writing is rewriting. And I’ll go even further, watching movies is watching them again and again. You’re never going to get everything the first time through, ever. When you start to rewrite a novel, you’ve written it once and as you’re going through, you’re discovering what things feel off. Sometimes it’s this person doesn’t have that kind of education or this description is flat. It only says one thing and it doesn’t work well. But there are other things there. It’s just something not right about this sentence, but it does everything it’s supposed to do. But the rest of the novel has a kind of a dance to the language, either the whole book or certain characters. You start to see and to recognize that when you are rereading.

When I finally read the novel out loud into a tape recorder and then listen to it, I can hear the music where it works. I can also hear where it doesn’t work. There’s a darkness, there’s a mood, there’s a lightness, there’s love. There’s all that stuff that you slowly begin to understand.

You have written fiction and non-fiction across genres and sub-genres. How do you manage that creative energy?

Waking up every day and writing for a certain amount of time. While I’m writing, I come up with ideas. I have an idea for a new novel right now actually.

The format and voice depend on the story I’m trying to tell. The other things, being black in America, all the genres have a real paucity of writers of color. I can write a Western, I can write an erotic novel, I could read all the science fiction, short stories, literary stories, and they’re all new because nobody put black people in those stories. They don’t exist in those stories. That makes it lots of fun.

The mere presence of black folks in American literature and popular culture more broadly is a disruptive presence. So much of the experiences of black folks across the Diaspora, especially in America, is almost like science fiction. It is surreal. It’s unimaginable. So it’s really hard to surprise us.

To be surprised on the morning that Donald Trump was elected? I don’t hold that against anybody. But the idea of thinking well, this is the worst and most terrible thing to have ever happened to America? Or that Trump is the worst president who’s ever existed? I told someone that, “Look, just a few presidents ago, George W. Bush was the worst president.” He completely destabilized the Middle East, all on his own. Bush was more a danger to the world. Trump’s going to come, Trump’s going to go. Bush actually changed the trajectory of the world.

The problem is not how upset or bothered you are, but rather about not being critical about the world in which you live. Living in White America you start to live according to fantasies.

There is a type of cynicism in America where what many once thought to be absurd, such as the CIA and the United States government actively facilitating the drug trade into black and brown communities as a way of financing covert operations, is now not even greeted with shock or amazement by most people. Black and brown folks certainly are not surprised as we were sounding the alarm decades ago. And of course, we see this real-life history in “Snowfall.”

If you’re black in America, you know the darker sides, no pun intended. You can say, “Well, I can’t trust the policeman. I can’t trust the courts. I can’t trust the schools.” There is no institution that you can trust; you have to work with them, but you can’t trust them. A lot of poor white Americans understand that too.

Most middle-class so-called white people live in a world in which everything is okay. It’s pretty safe, it’s nice, and because of their experience, they have a view of the world which is quite different than if you’re working class or poor black America or Mexican-America. There’s all different Americas. The way I look at things, and I’m sure the way John [Singleton] was looking at things, he says, “I want to tell my audience the story about their life. [If] somebody else wants to listen to it and see it and learn from it, I’m happy.”

The black people who were John’s age and had gone through that same experience either in Los Angeles or other places say, “Oh yeah man, that’s true. All of that happened. That’s the truth.” The idea of having the truth come out around and behind and in spite of this other kind of myth-making, it’s just wonderful. The more you can believe it’s possible to attain the truth, to speak the truth, that’s the more you’re going to be able to make something that makes sense to you.

The myths and lies that middle class and other privileged white folks tell themselves about America and reality are very evocative of the movie “Forrest Gump.” That film is a powerful representation about white folks – in particular, white men – as bystanders of history. “Forrest Gump” is a powerful depiction of a very specific type of whiteness and white privilege.

I like watching movies that are just fun to watch. They’re fantasies of some sort and like in “Lord of the Rings” the tiniest hobbits win against the biggest, most evil forces imaginable. We like that, because that’s kind of how we feel. We feel we’re small. Everybody in America feels they’re small. They hope to survive. You can make it, you can live a happy, fulfilled, wonderful life.

I really like “Snowfall.” It’s a really tough story because your heroes are bound for destruction and you can’t even be against it. You don’t want to see anything bad happen to them. Those are the white heroes of America in the ’30s: Bonnie and Clyde, Babyface Nelson, Machine Gun Kelly, and Al Capone. Everybody loved them and wanted them to be happy. I’m sure a lot of people wanted El Chapo to somehow get out of that situation because they represent, to a great degree, what we want. “I want to be John Dillinger. I’m tired of being poor. I’m tired of a Depression that I didn’t cause.” John took a step further with “Snowfall” where you get deeply into the minutia of the development of these characters. It’s kind of wonderful.

What are the decisions being made in terms of balancing the truth and the demands of the television format on “Snowfall”?

You have to edit. You have to say, “Well, I can talk about this, but I can’t talk about that.” It’s like being in Grand Central Station. How am I going to make people believe they’re here without showing them all of Grand Central Station? Part of it is the knowledge of the people in the writers’ room and what they already know. There’s a hierarchy in the writers’ room. People are deciding where the story is going to start this year and where it’s going to end. Once you make that decision, you get rid of a lot of things. So I say, “Well, let’s bring this in.” Then it’s, “Well, yeah, we can bring that in, but it’s not going to help us get to the end of the story.” You can’t tell every story and idea. You have to decide on what to do.

John was never oppressive where it was just where we had to do what he said. We’d argue about it. We go back and forth and either we would do something he wanted to do or we wouldn’t. And John accepted that. There would be moments where John could fight a little harder than some people for his vision. But in the end, that’s what we all do. We all listen to each other and write the show.

How did John Singleton grapple with the legacy of “Boyz n the Hood”?

On the 25th anniversary of the movie, he was at a screening in New York and I introduced him. John was extraordinarily pedestrian in his way of understanding himself. He was born in the hood. He lived in the hood. He died in the hood. John was still living there when he died. John made his films for his people and he brought his people in to make his films. John was so committed to who he was, where he was from, and what stories he wanted to tell. John got his gratification from his audience, his people understanding what he was doing. One day somebody said of “Boyz n the Hood” that, “Well, it’s not ‘The Godfather.’” And I told them, “Yeah, in one important way, it’s better than ‘The Godfather.’’’ They responded, “What do you mean?” And I said, “Well, it was a completely new film. It was a film that nobody in America had ever seen.”

And there have been very few films that come anywhere near to “Boyz n the Hood” because John was so clear that he was talking about his people, his place. He wasn’t talking about the false images that people held of themselves. “I’m the sexiest, I’m the smartest, I’m the best fighter. I can shoot behind my back and hit you between the eyes”. No, he didn’t have that nonsense. He showed that these are people who live in the hood and trying to survive and who understand life in certain kinds of ways. These people are not all the same. They’re often in conflict with one another.

People who understand film, understand that about “Boyz n the Hood.” John changed the trajectory of film because he did something new and he knew that. There are not many people like John Singleton. Not very many at all.

In terms of “Snowfall,” how do you want the viewers to feel after watching the show?

I can’t answer that until we get to the end of the series. But it is not an easy question to respond to. This is not a class that says at the end “as students you should understand all of these things.” Yes, after watching “Snowfall,” you should understand how black people became enmeshed in destroying their own community. Yes, you have to understand how the CIA and an American general said, “Well, it’s okay if we lose all these black people because we’re doing something more important on some higher level.”

If you saw “Snowfall” in the theater, I think you should come out of the theater arguing. And I think that’s what John would want. We only grow through disagreement.