Time and again questions about political messaging have been posed to Dick Wolf, the man who has far and away defined the modern procedural genre since the first “Law & Order” premiered the fall of 1990. Nearly three decades later, its spinoff “Law & Order: Special Victims Unit” is one of the longest-running series in TV history. It also shares the schedule with Wolf’s Chicago franchise on NBC (“Chicago Fire,” “Chicago PD” and “Chicago Med”) and his CBS series “FBI” and “FBI: Most Wanted.”

If ever there were a person in a position to influence conversations about inequities in the justice system or cement perceptions about the actions of law enforcement in the United States, it is Wolf. And yet at a recent press conference in support of his soon-to-debut spinoff “FBI: Most Wanted,” when a reporter asked if he sees his series “as some kind of answer to the real world” with regard to his depictions of federal law enforcement agents versus the way that Donald Trump frequently refers to them, Wolf stated, as he has before, that he is merely in the business of telling stories.

“This is not a political show,” Wolf said, explaining his view of the FBI are informed by family history; his uncle was an agent. “I think that it’s an apolitical organization for 98 percent of the people who are carrying badges.”

He went on to extend this philosophy to all of his series: “If you go back over the 35 years that I’ve been doing this on any of these shows, there’s no upside in politics. At best, a political story pisses off either 49 or 51 percent of the audience before you start doing anything, and you get it all day long on Fox and CNN. We are not making political statements in any way, shape, or form.”

As for social statements about law enforcement, a new study from the social justice non-profit Color of Change and the USC Annenberg Norman Lear Center’s Media Impact Project beg to differ.

“Only someone who doesn’t have to suffer the consequences of a criminal justice system would say that these shows are apolitical, would say that these shows don’t have consequences,” said Rashad Robinson, President of Color of Change. “Only a very rich, guarded individual that doesn’t have to deal with the consequences would say that.”

“It’s as if Dick Wolf is living in a country that it did not have uprisings in cities with people yelling, ‘Black Lives Matter,'” Robinson added. “It’s as if Dick Wolf is not living in a country that had a struggle to pass a bipartisan criminal justice reform bill . . . Only someone who is operating in a totally different context would stand in front of a room and say that [his work] is apolitical. Only someone that is completely cavalier about the consequences, because they don’t have to suffer them, would believe that.”

The study, titled “Normalizing Injustice: The Dangerous Misrepresentations That Define Scripted Crime Drama,” draws some damning conclusions about how fictional misrepresentations of the criminal justice system on television may be thwarting the cause of enacting real and much needed reform. It’s an exhaustive report, with the full version weighing in its findings across 78 pages and the abridged version coming in at 38.

But it is worthwhile reading due to the way that it breaks down well-established tropes, such as the notion that Black judges are a frequent sight in courtrooms, which is in contrast to reality. This is a problem, the report explains because “Black judges project the legitimacy of the system: lending the credibility, moral weight and moral approval of the story of African American history to brand the drama playing out in front of the viewer — and the real-life system it represents — as fair and just.”

It also points out that the average public defender spends around six minutes total with each client, contrary to what many series depict. This misrepresents “the level of access to capable defense that all accused people have.”

While the report states that sensationalized crime coverage on local and national news bears its share of responsibility for the public’s inaccurate perception about the justice system, “there is no stronger public relations force working against reform than scripted television,” it states. “Whether intended or not, some of the most popular television series of the last three decades have also served as the most effective PR arm for defending the system, especially the police.”

It continues, “Most series in the crime and legal genre continue to miseducate the public about crime, race and the system itself. They do so in ways that undermine reform, demonize people of color and serve to legitimize debunked policies, discredited arguments, corrupt decision makers and (what should be) indefensible actions.”

The study, which draws its findings from an analysis of 353 episodes across 26 crime-related scripted television series in the 2017–2018 season, goes beyond mere data count to contextualize the actions depicted in TV episodes evaluated in the study.

“What I oftentimes think about, imagine if medical shows were consistently putting out false information about cancer or diabetes or HIV and AIDS,” Robinson said. “People would speak out and push back. But we have our criminal justice system, which is one of the most consequential systems we have in this country, constantly being portrayed in a false and misinformed way on television to huge ratings. And the only thing people seem to care about are the products.”

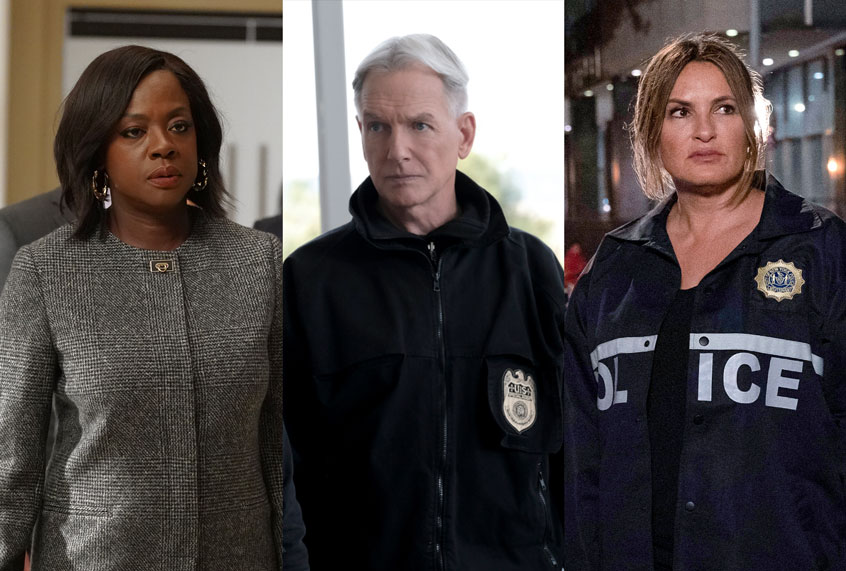

To be clear, “Normalizing Injustice” does not specifically target only Wolf’s shows. But it does include two of them: “Chicago P.D.” and “Law & Order: SVU.” (The first of his “FBI” series debuted outside of the date range of the study’s focus, which count episodes that aired between March 2017 to July 2018.)

They are among 26 crime dramas included in the report, nine of which air on, you guessed it, CBS: “Blue Bloods,” “Bull,” “Criminal Minds,” “Elementary,” “Hawaii Five-0,” “NCIS,” “NCIS: Los Angeles,” “NCIS: New Orleans” and “SWAT.”

The study also looked at five Netflix series, including “Luke Cage,” “Mindhunter,” “Narcos,” “Orange Is the New Black” and “Seven Seconds”; and five on NBC: “The Blacklist,” “Blindspot,” “Chicago PD,” “Law & Order: SVU” and “Shades of Blue.”

Three of the series evaluated air or aired on Fox, “9-1-1,” “Brooklyn Nine-Nine” (which has since moved to NBC) and “Lethal Weapon”; and three come from Amazon, “Bosch,” “Goliath” and “Sneaky Pete.” The study also includes one from ABC, the Shonda Rhimes executive produced series “How to Get Away with Murder.”

Within these series, the coders looked for what the study finds to be distorted depictions of crime and justice with regard to race, gender. The organization commissioned the report as a follow-up to its 2017 study that found the crime TV genre was the least diverse of all television genres in terms of hiring Black writers. And given how many criminals and suspects happen to be Black, the connection became obvious.

This study, however, closely looks at unlawful and unethical actions committed by law enforcement agents themselves that get a pass because within the narrative, they are done in the service of “good.” “Normalizing Injustice” describes these characters as “Good Guy” Criminal Justice Professional characters or, CJPs, or “Bad Guy” CJPs.

It also employs a metric called the Person of Color Endorser Index as a means of analyzing the number of wrongful actions going unacknowledged that also prominently feature people of color CJPs. Lastly, it utilized a Racial Integrity Index that ranks each series by the number of people of color depicted committing these action set against the percentage of people of color writers in its writers’ room.

Cutting to the chase, the findings are about as depressing as one might suspect. In every series “wrongful actions,” i.e. those exciting moments that aren’t quite by the book, are normalized or excused to make bad actions committed by CJPs seem justified, or even good. Three times as many CJP characters are seen committing wrongful actions versus all characters, and a number of series used people of color to validate that “wrongful actions” either by committing it or endorsing it. The worst offenders? “Luke Cage,” “9-1-1,” “How to Get Away with Murder,” “Lethal Weapon” and “Elementary.”

The report finds that “Law & Order: SVU,” “The Blacklist,” “Blindspot,” and “Blue Bloods” showed characters endorsing illegal practices most frequently.

As for who are the victims of these crimes: 35 percent are white men, 28 percent are white women, 22 percent of the time they’re men of color with women of color portrayed as victims 13 percent of the time. Further breaking this down, Black men are seen in these shows as victims 12 percent of the time, with crimes against Black women coming in dead last in terms of frequency, at nine percent.

“Law & Order: Special Victims Unit” holds the title of the highest number of female victims, but with the lowest percentage of those victims being people of color.

Those wrongful actions might refer to witness coercion and intimidation, racial profiling, unwarranted force, abuses of power and corruption and other examples. And 69 percent of the series analyzed, or 18 of the 26 series, depicted a “good” CJPs committing one of these acts or another wrongful action not listed here. And 64 percent of the time a character acknowledged that what was done wasn’t right, that character was either a person of color or a woman, which says quite a bit about who is required to express contrition and take responsibility for negative actions, and who isn’t.

The new report ties in these findings to data about inclusion, or lack thereof, in writers’ rooms. The study points out that last season, 84 percent of the writers across the 19 series profiled for that season were white, and only four series had fewer than 80 percent white writers. “The Blacklist,” “Law & Order: Special Victims Unit” (also nearly 60 percent male), “Blindspot,” “NCIS,” “Blue Bloods” and “Elementary” each had writing rooms that are 100 percent white or close to it, according to the report.

Six shows on CBS and three on NBC have no Black writers at all, and all of the series except for “S.W.A.T.” employ black writers at a rate of 15 percent or less. Meanwhile, Robinson points out, crime shows employ law enforcement representatives as consultants as a regular practice.

And the report does give credit where it is due, citing limited series such as CBS’ “The Red Line,” Netflix’s “Unbelievable” and “When They See Us,” the CBS All Access drama “The Good Fight” as having used the system’s failures in accountability to inform the storytelling as opposed to gliding by them. It also says the same of Netflix’s “Seven Seconds” while also calling out the series for its stumbles in portraying the malfeasance of CJPs.

You may also notice that two of those series, “When They See Us” and “Unbelievable,” are based on real-life cases.

I’ve written about this problematic filtering of the justice system through the procedural factory a number of times during my career, and the situation hasn’t gotten markedly better over the years. In fact, with more TV series on the air, we’re flooded with these series that drive home “Law & Order”-style myth that the system is equitable, that it works, and justice can be served.

But these shows also assist in proliferating damaging misperceptions about crime in America that leads people to believe that extreme policing is just and necessary. Multiple studies have concluded that regular viewers of primetime procedurals believe that the violent crime rate in America is on the rise when, in fact, it is in decline.

Equally as worthy of examination is the level of humanizing law enforcement characters receive in these television series versus the people they interact with, be they suspects, victims or witnesses.

“The most developed character on television is the police officer,” Robinson points out. “They may be a racist or they may have an alcohol problem, or they may be unfit in some way for their job. But you learn the season before why they are that way. You begin to humanize them. And the community that they are engaged in, the poverty that’s oftentimes shown, the challenges that are oftentimes there [are] almost always glossed over.”

Robinson stresses that the report isn’t meant as a call to end these shows. “We want to push these shows to tell a more authentic narrative . . . Police departments don’t need hundreds of millions of dollars of free public relations, and that’s what they’re getting right now.”