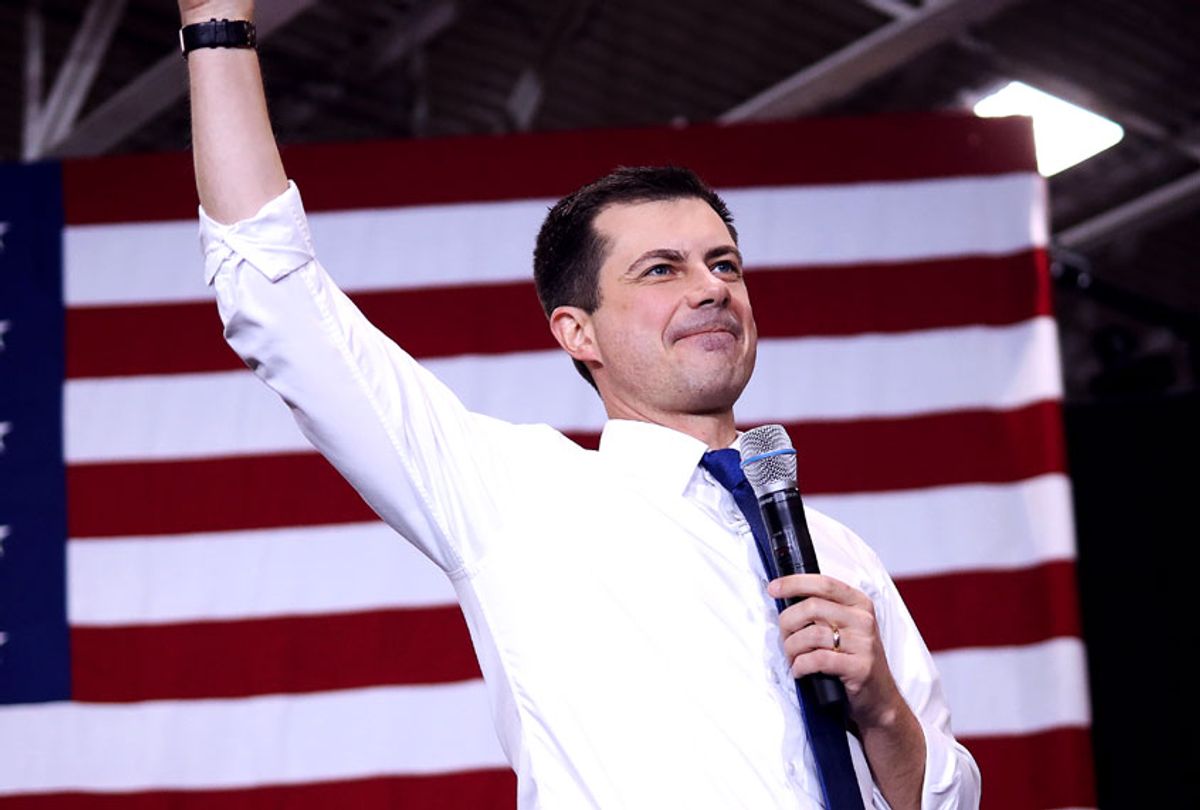

After the surprise results of the Iowa caucuses — in which the former mayor of South Bend, Indiana, Pete Buttigieg, tied with polling favorite Sen. Bernie Sanders, each pulling in a little over 25% of the vote — conspiracy theorists supporting Sanders got a little nuts online. The assumption was that the Democratic "machine" had somehow rigged the results in favor of Buttigieg, viewed as an "establishment" favorite.

That idea was silly for many reasons, not the least of which being that more established Democrats with actual establishment support — former Vice President Joe Biden and Sen. Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota, most notably — would have been a better choice for such a conspiracy than a green young man who (until now) has had little actual establishment support. But even skeptics of this conspiracy theory, such as myself, didn't question the notion that Sanders is an outsider candidate.

Then I interviewed Buttigieg supporters on the ground in New Hampshire, and a very different interpretation of the Iowa results came out. To them, this is a classic David vs. Goliath story — and Mayor Pete is the scrappy underdog who bested the powerful, famous Sanders.

"He has come from virtually nowhere," Jeff Brinkman, who was visiting New Hampshire from Indianapolis, told me. "I mean, he beat Bernie Sanders at Iowa. What does that say about him?"

"Pete pulled out a win against Bernie Sanders," echoed Jimmy Kyriakoutsakos, a lifelong New Hampshire voter who argued that "everybody knew who Bernie and Biden were," but, "six months ago, nobody knew who [Buttigieg] was."

"A win is a win," Kyriakoutsakos declared. "Amazing!"

These opinions will no doubt lead to much gleeful dunking from extremely online Sanders fans, in their eternal bid to seem edgy and cool and totally not like they were big Ben Folds fans in high school. But as odd as it might seem to the Twitterverse to view Buttigieg as more of an outsider than Sanders, it makes a lot of sense that people who are a little less obsessed with politics might see it this way.

Sanders, after all, is a U.S. senator with more name recognition than perhaps any other politician who has not been a president or a vice president — or been married to one. Buttigieg, on the other hand, is a small-town mayor few people had heard of until a few months ago. From a certain point of view, Buttigieg is obviously the little guy.

There was a sense, in much of the punditry after the Iowa caucuses, that Buttigieg was consolidating the more moderate vote after Joe Biden collapsed in the polls there. But the crowd of Buttigieg supporters who showed up at the annual McIntyre-Shaheen dinner were loud and boisterous, filling the arena with chants of "BOOT EDGE EDGE," and showing that the enthusiasm for this unlikely almost-frontrunner was quite real.

That came-from-nowhere quality is characterized by Buttigieg's opponents — particularly Klobuchar, who is his primary competitor in the "moderate lane" — as a lack of experience. For Buttigieg fans, that's a plus. He was repeatedly compared to Barack Obama, Bill Clinton and even Jimmy Carter — candidates who also seemed to come out of nowhere, but who had a dazzling intellect that helped them sweep their way into office.

"I heard him speak on MSNBC," Mary Stevens, who attended a Buttigieg rally in the small, northwestern town of Lebanon, New Hampshire, said. She was impressed because "he could answer every single question without skipping a beat."

She liked the other candidates, but felt they were "Washington politicians." She saw that scrappy underdog quality in Buttigieg, however, saying that "he's been bullied his whole life" and that meant "he would be able to handle Donald Trump".

"People want fresh ideas," Blake Kurisu, who had come from New York to canvass for Buttigieg, told me. "Frankly, people want untraditional candidates that can bring new ideas to a country that is tired of having Donald Trump as president."

Lack of experience, looked at from another angle, means a lack of baggage. When Bill Clinton, Obama and Carter ran, that was something they brought to the field: They were new and relatively unknown, so it was easy for voters to project their hopes and desires onto them, without the image getting muddled by any actual flaws.

There's actually a good reason, if a slightly depressing one, to think these voters are on to something. As I've written about before, Trump and his allies are planning an almost exclusively negative campaign, based on trawling through the Democratic nominee's history and finding whatever can be used to create fake scandals or to discredit that person in the eyes of progressives, so as many likely Democratic voters as possible simply stay home. Buttigieg's paucity of history, then, means giving the rat-f**kers less to work with.

(Trump's hired guns will not be completely empty-handed, when it comes to Mayor Pete. His dismal record on racial disparities in law enforcement as mayor of South Bend is a time bomb that would be detonated at convenient moments during the general election campaign, with the goal of discouraging black turnout.)

As with Obama and Clinton, Buttigieg's identification with a marginalized group adds to that underdog appeal. Clinton's hard-scrabble Arkansas childhood set him apart from the moneyed elite in Washington politics; of course, Obama is not just black but has an unusual name and partly grew up overseas.

"I never thought in my lifetime, I'd see a gay person come this far," said, Michael Schaefer, who is married to Brinkman. "I'm shocked that that's happened so quickly, you know?"

None of this is to deny that Buttigieg's recent rebranding as a more moderate candidate has had an impact. A number of voters flagged that as a plus, either because they identified themselves as moderates or because they thought it would allow Buttigieg to appeal to a larger voting base.

The Buttigieg debate watch party in Manchester was held at the Breezeway Pub, a fairly typical downtown gay bar, complete with chipper dance hits blasting, the rainbow-colored lights and dark walls, and aggressive beer advertising. As I sat at the bar chatting with a regular before the debate, a group of conservative-looking boomers, sticking out as much as polar bears in Florida, came in and took over one corner of the bar, chattering happily.

"Lifelong Republican voter. Straight-ticket Republican vote," Richard Leland from Durham, California, told me. But even though he liked some of Trump's agenda — "conservative judges, lack of regulation and tax reform" — he was opposed to the human rights abuses on the border and Trump's approaches to terrorism and foreign policy.

Leland cited Buttigieg's centrism as his main appeal, but also liked that Buttigieg "served in the military, which for commander in chief is a pretty nice credential."

Leland wasn't entirely decided yet, however. He also liked former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg, despite the fact that Bloomberg was now "walking back" the stop-and-frisk policy that Leland felt had "made New York a safer place to hang out." (To be clear: Research shows that stop-and-frisk did not reduce crime in New York.)

Jon Estey, who wore a donkey hat at the Lebanon rally — the same one he wore, he said, "the night that Bill Clinton gave his comeback kid speech" in 1992 — said that he was all in for Buttigieg, whom he called "a great moderate" and "appealing to the general voter." Like nearly every Buttigieg supporter I spoke with, he flagged the former mayor's intelligence and military experience as major assets, as well.

After speaking with Buttigieg supporters, it became clear to me that his speeches, which have always struck me as bland and uninspiring, are cleverly crafted to speak to these aspects of his political brand that appeal to voters. His speech Saturday night at the McIntyre-Shaheen dinner made a lot more sense in this light.

His appealing newness and lack of baggage? Check. Buttigieg said that while his critics say, "You don't have decades of experience in the establishment," he argues that this lack of experience "is very much the point," because he stands for people who "are tired of being reduced to a punch line by Washington politicians."

His moderation? Check. "With a president this divisive, we cannot risk dividing Americans further," Buttigieg said, shading Sanders by saying that it wasn't true that "you must either be for revolution or you must be for the status quo."

That Clinton-esque or Obama-esque sense of intelligence and reasonableness, as a counterweight to GOP ridiculousness? Check. Buttigieg contrasted himself with Trump, noting that he "lives in a middle-class neighborhood in the American Midwest," is a Christian who is "not afraid to remind fellow believers that God does not belong to a political party," and is a "war veteran." He hardly had to mention that Trump is a draft-dodger and faithless hypocrite, who lives in a gold penthouse on Fifth Avenue.

There's a strong chance that Buttigieg, with his wholesome small-town persona, will only do well in primarily white and rural states like Iowa and New Hampshire, and will hit the shredder when faced with more urban and racially diverse Democratic voter bases in the weeks ahead. In fact, I would still bet a lot of money that is exactly what happens.

But it's a mistake to wave away the fact that Buttigieg has real appeal, especially to people who feel nostalgic for the way that similar figures like Clinton, Obama and Carter offered voters a chance to wipe the political slate clean, after it had been befouled by Republican scandals and war-mongering.

Shares