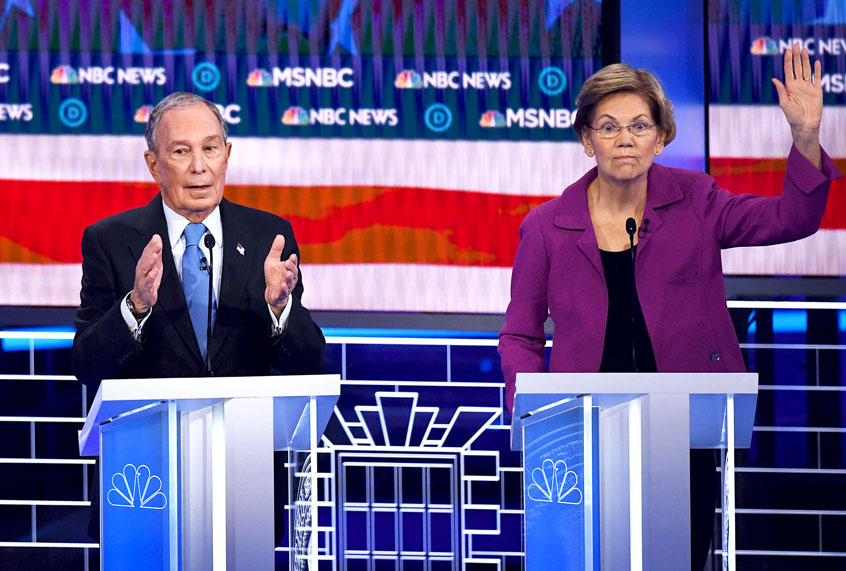

The media has gone a little bit nuts (in a good way) over the opening salvo from Sen. Elizabeth Warren during the Democratic primary debate in Las Vegas Wednesday night. Everywhere one turns, Warren is being quoted again, calling out former New York mayor Michael Bloomberg, currently the 12th richest person in the world, as an “arrogant billionaire” who “calls women ‘fat broads’ and ‘horse-faced lesbians.'” It was a clock-cleaning so beautiful that political junkies just keep rerolling the tape, like it was the sweating, flu-ridden Michael Jordan ending the Utah Jazz in the 1997 NBA Finals.

But what’s remarkable about Warren’s quote wasn’t just that it was an epic dunk on the sour-faced Bloomberg. It was also because, she seamlessly weaved together two progressive frameworks that tend to be kept in separate bunkers by most other politicians: Her feminism and her critique of capitalism.

As Greg Sargent of the Washington Post wrote Thursday, this was Warren tying together what one might call Bloomberg’s “#MeToo problem” with the way he wields his wealth as a shield from accountability, all under the banner of “elites acting with impunity.” It also makes Bloomberg sound a lot like Donald Trump, whose impunity while he “boasts about sexual assault” is tied to his more general sense of financial and legal impunity.

Warren’s ability to pull off this linkage of sexism to a larger criticism of elite abuse of power — and really, it was a hat trick, since she also tied all that together with Bloomberg’s history of “supporting racist policies like redlining and stop-and-frisk” — wasn’t just the result of some clever writing from her strategic team, however much they may have helped. This fits in with a larger pattern with Warren, whose feminism is simply inseparable from the issues that have defined her career, namely her opposition to predatory capitalism and her war against the ways economic elites corrupt our political systems.

This goes all the way back to the time before Warren was in politics, when she was a law professor who specialized in bankruptcy law. As Warren has often recounted, she started off studying why American families go bankrupt. The prevailing conservative theory of the ’90s was that bankruptcy was caused by middle Americans being too greedy, and borrowing more money for shiny consumer goods than they could afford to pay back. Therefore, the thinking went, they should be punished for their recklessness and not be allowed to file for bankruptcy.

Warren’s research, however, showed that most people over-borrow because they’re trying to pay basic bills, like for housing and medical costs. Even though Americans were bringing in more income, they were seeing bills and debts rise even faster.

But what was really innovative in Warren’s thinking was the way she put the fact that women were working in greater numbers than ever before at the center of this story. She co-wrote a book with her daughter, “The Two-Income Trap,” arguing that the shift away from women staying at home to dual-income households meant that wives no longer functioned as insurance against financial losses.

“If her husband was laid off, fired, or otherwise left without a paycheck,” Warren and her daughter, Amelia Warren Tyagi, wrote, the old-fashioned stay-at-home wife could look “for a job to make up some of that lost income.”

But nowadays, both parents have to work in order to pay the bills, which means there’s no way to make up for lost income or a sudden expense by putting an otherwise non-income-bearing spouse in the job market.

There are various ways to understand the implications of what Warren, a Harvard law professor when she wrote that book, was arguing. One is a more conservative argument, which is that by driving women into the workplace, feminism removed this insurance against bankruptcy. Indeed, many conservatives have latched onto Warren’s arguments for precisely that reason.

But another argument, one that Warren herself advanced at the time and has since put forward more bluntly, is that the problem isn’t that women work. It’s that the capitalist system has adjusted in ways that exploit families. That second income into households wasn’t making families wealthier — it was just allowing the capitalist system to drive up the cost of everyday living and maximize profits. And it should be the job of the federal government to step in and change the system so that women’s work can do more for their families economically.

Yes, Warren was justifiably critical of feminist organizations back then for bucketing these economic considerations outside the larger concept of “women’s issues”.

“Women’s issues are not just about childbearing or domestic violence,” Warren and Tyagi wrote. “If it were framed properly, middle-class economic reform just might become the issue that could galvanize millions of mainstream women to join the fight for women’s issues.”

In the years since, Warren’s feminism has gotten sharper and, at the same time, feminism has become more interested in these kind of economic concerns. For instance, the issue of subsidized child care, which had been tabled for decades after activist campaigns around the issue in the 1970s had failed, has risen to the top of feminist concerns in the past decade.

Most Democrats have embraced some policy ideas for making child care more affordable, and none so more than Warren, who has released a detailed plan for universal day care — which she wants to pay for by taxing the wealthy, which is a double whammy, lifting women up economically while also reducing wealth inequalities.

Similarly, the reproductive rights movement has broadened its agenda away from focusing on just the legal right to abortion to economic concerns regarding health care affordability and access, as well as making sure that women’s economic futures aren’t derailed by unwanted child-bearing. Feminist groups threw themselves wholeheartedly behind the Affordable Care Act, for example, and worked to make sure that women-specific concerns, like prenatal care and contraception access, were central to it.

Warren’s key insight from her legal career until now is that women are economic actors, and this fact cannot be siloed off from other women’s issues. She brings that insight to her presidential campaign, where she talks about women’s issues and economic issues as one and the same thing, from highlighting women’s central role in labor organizing to tying elite economic corruption to the problem of sexual harassment, as she specifically did on Wednesday in Las Vegas.

In many ways, the time is ripe for such a nuanced point of view. The #MeToo movement is as much, if not more, a labor rights movement as it is a feminist movement. While there certainly were stories about non-consensual sexual behavior outside a work environment, most of the stories — and nearly all the most high-profile ones — were about men leveraging their power over women’s job opportunities and salaries in order to sexually humiliate women.

In other words, #MeToo doesn’t happen outside of the cultural shift that Warren catalogued earlier in her career, in which women’s presence in the workplace stops being controversial and starts being completely normal. The idea that women should quit if they don’t like the way men treat them is no longer part of the conversation. The fact that women have as much right as men to hold a job as men is finally — finally — becoming the baseline assumption.

On the other hand, the political pressure to put “women’s issues” in a silo separate from economic issues is still tremendous. None of the other Democratic candidates really talk about the two as if they’re one and the same, as Warren does. Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont, for instance, has all the right policy positions on feminist issues. But he tends to speak of them in perfunctory terms before getting back onto economic issues, which he talks about in mostly gender-free terms (which tends to default to male, at least in the audience imagination).

Former Vice President Joe Biden, on the other hand, made violence against women a central issue in the ’90s and still feels passionately about it. But he rarely speaks about it in terms of how it affects women economically. For instance, Biden got angry with Bloomberg Wednesday over the fact that Bloomberg won’t release women who have sued him from non-disclosure agreements. Biden said that many of the women wanted to speak out but Bloomberg “comes along with his attorneys” to pressure them into silence or pay them off.

But Warren took it a step further during that same exchange, emphasizing that this is a “gender discrimination” issue. She continued to root the debate in the fact that these women worked for Bloomberg, mocking him to his face as he lamely tried to cite all the women who worked for him who haven’t sued him. As Warren put it, “I’ve been nice to some women” doesn’t even come close to covering all the women who have worked for him.

This is about more than the fact that Warren is a woman in what remains the male-dominated field of upper-level politics. Most Democratic women deliver about the same patter as the men, where they talk about women’s issues as if they were in some separate category, largely unconnected to economic issues. Hillary Clinton got away from that some, to be fair, tying her story about her professional work to her concern for women’s and children’s rights.

But no one in politics talks about feminism and economic progressivism as one and the same issue the way Warren does. That’s because her political awakening started with research into women’s economic roles, and her entire understanding of the economy is refracted through that initial interest in women as workers and consumers. It’s a feminism that is both badly needed and poses a real threat to those in politics, including some feminist organizers, who would just as soon keep those issues separate. But it’s also a huge source of Warren’s appeal, especially among women who are glad to have a politician who speaks of us as whole people, and does not relegate us to the “women’s issues” ghetto.