As a genre, science fiction offers a vision of the future. But that vision is filtered through the present and the past. The way that a given science fiction story negotiates those tensions is one of the factors that separates the truly great from those stories which are middling, common, and forgettable.

Gene Roddenberry's "Star Trek", which debuted on American television in 1966, endures because his hopeful vision of a future human society that had survived and matured beyond war, racism, sexism, bigotry, famine, greed, nationalism, environmental destruction, and other anti-social behavior, inspires its audience to be their best selves.

Over the course of more than five decades, Roddenberry's initial vision of what he described as "Wagon Train" set in space and with a "message of the week" grew to include eight television series and now 13 films. The "Star Trek" universe – for better and for worse – also includes a plethora of novels, comic books, and video games.

More than 50 years later, how has "Star Trek's" original and hopeful vision of the future reconciled itself with a human society that seems – especially at present with the Age of Trump and the rise of the Global Right – to have betrayed its best potential?

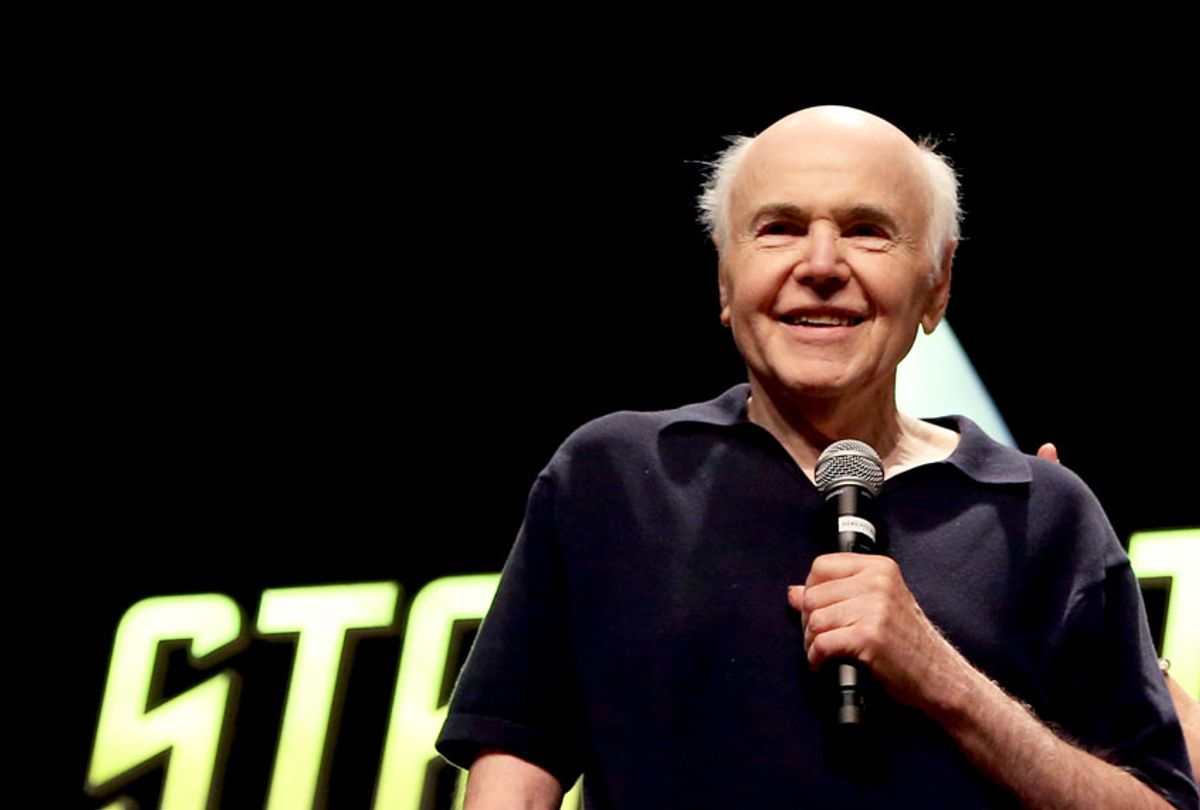

In an effort to answer that question, I recently spoke with Walter Koenig, who had portrayed the Pavel Chekov on the original "Star Trek" series and in seven of the subsequent canonical films. "Generations" was Koenig's final appearance in the official "Star Trek" films.

In this conversation, Koenig shares his deep worries and concerns about the state of the world and American society in the Age of Trump. Koenig also reflects on both the power and dangers of hope in troubled and challenging times. Koenig also shares how he found acting as his vocation and the ways that he tried to best embody Chekov on "Star Trek" and the character Bester on "Babylon 5".

The actor also explains what it means for him to finally start to walk away from the character of Chekov by no longer attending as many "Star Trek" conventions and other popular culture gatherings and events.

Koenig will be appearing this week, Friday, Feb. 28 to Sunday, March 1 at C2E2, the Chicago Comic & Entertainment Expo, which is held at McCormick Place.

This conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

It has been 50-some years since the original "Star Trek" debuted on television and yet, here we are still talking about the series. How are you feeling? How are you reconciling "Star Trek's" hopeful vision of the future with where we have ended up in the United States and around the world?

"Star Trek" and the state of the world? On one end it is an atomic pit where an explosion has just occurred. The state of the world is dreadful. It depresses me to no end. "Star Trek" is a welcome respite from the infamy of the Trump administration and all the problems we are living with. "Star Trek" was always positive. A very strong part of me that wants to leave "Star Trek" behind. To have it be such a central part of my life at this stage does not speak well for what else I have accomplished given that people are still harking back to a time that is more than five decades old.

On the other hand, it was a good time. It was a pleasant time. I have friendships that endured throughout this half century because of "Star Trek." I am pleased that I am still here and in good health. I appreciate that. I do conventions these days, although I am in the process of winding that part down. This is the first year that I've actually said to my booking agents that I'm limiting my appearances. I do enjoy being there. I enjoy talking to fans. And then I get to see actors who I've worked with. It is a kind of reunion. Meeting other performers who I have worked with before is also fun.

Where do you think we went wrong?

We're doing the same thing we've done for as long as humankind has existed. We go through cycles. We think we are approaching a new era, and a new way of thinking with more progress and being more humanitarian and possessing a greater awareness and respect for other people of different racial and ethnic and cultural backgrounds and then we revert and regress. America is as much to blame as any other country. We've gone through slavery. We've committed genocide against Native Americans. We seem to be taking a step forward, and then we take a step backward.

I think this is a particularly heinous moment in American history with Donald Trump. This is not only because of a few individuals who now have control of the government but that there is so much support for them. There's so much vitriol, discontent and anger. These people are willing to sacrifice the good things in our culture and in our life to support evil things. We as a country and a culture have not gotten to a positive place of progress from which we are not willing to retreat from.

It just goes on and on. We have the good folks, the people that we believe in. For example, when Barack Obama became president, I thought to myself, "My God. We have really turned a corner. I am so proud to live to see this happen." And then we have Donald Trump. There is a certain despair that follows me, that haunts me, because we're still doing the same things.

Roddenberry's vision of the future was so hopeful. Science fiction as a genre can also be very hopeful as well – while still issuing warnings about how it can all go wrong. In moments such the Age of Trump and all its darkness and pain is hope a dangerous thing? How do we balance hope and despair?

If we do not have hope, then we're surrendering. Then we're giving up. Hope may be temporary. It may last for five years or 10 years. We are driven to make things better. We have that dream to make a better world. If ultimately it all crashes, then the ugly parts of human nature come to the surface and those attributes become the dominant characteristics of a culture and a society. That is sad and very depressing. But I think that our only choice is keep that hope going to make things better.

When you reflect on your career and life, what is the narrative? How did you make the decision to become an actor?

I was one of those kids who was a little bit on the retiring side, I was a little shy. I did not have a lot of positive self-image. The only time when I really felt like I had some importance was when I was acting. I go back to the sixth grade. I had a stutter until I took the lead in the school play and that killed the stutter. Then I went to private school, and I was still a type of background personality until I did the lead in my sophomore year high school play. That made me quite popular. Everybody wanted to be my friend. Then it happened again in my senior year, and then I did the lead my freshman year at college, in Iowa, of all places.

All that time I thought I was going to be a psychiatrist. Then, when I realized I had no aptitude for physical science, I switched to psychology and got my degree in that area of study. But then I transferred to UCLA – and just as a reprieve from all the academics – I took one acting class. I ended up with an instructor who had a lot of faith in me. He was the one that actually laid it out for me. He told me, "You're not married. You don't have kids. You have no responsibilities. Why don't you give it a shot?"

Based on his recommendation, I went back to New York and started at the Neighborhood Playhouse. Chris Lloyd and Dabney Coleman and Brenda Vaccaro and Elizabeth Ashley and Jessica Walter were all there. I knew then, that first year at the Neighborhood Playhouse, that acting was it for me. There was no turning back. This is where I felt I had a home. I had no idea whether I would have any success. I'm confident that I was not one of those students who anybody anticipated might see some recognition.

How did you make the decision? Was it internal will? Something else?

I don't think it was a specific moment. I think when I saw how much I was enjoying going to school it just sort of settled in. I don't think there was any one moment I just said, "Okay, now I am a student, and in a couple years when I finish drama school, I'll be an out of work actor, like everybody else, and then what do I do?" By then, it was already determined. I didn't have any one moment where I to decide to make it work.

I came out to L.A. because I thought I was going to do a movie with Burt Lancaster and Shelley Winters. I had been seen by somebody who was assistant to John Frankenheimer on a picture that he was doing, and he had recommended me because of a play he saw me in at the Neighborhood Playhouse. Well, I got out here, and it didn't work out. And the day I found out that it wasn't going to be in the play was a Sunday.

I was off doing a first reading for a play that I had auditioned for and that I then got. It was about a half hour drive, and I got to the studio where we were going to start rehearsing and then I found out I wasn't in that, either. They had recast the play without telling me.

So, I walked out that door saying to myself, "Jesus. If I still feel I want to be an actor tomorrow, then it's a creed. You know, this is my baptism of fire, and if I survive this, that's it. I don't have to think about anything else." And I did. I woke up the next morning and said, "I'm still an actor." That's how it started.

How did you develop your voice and style? For example, Chekov is very different from Bester on "Babylon 5." Bester is very menacing while Chekov is not.

I really don't know if it's that different. Certainly, I had a dialect as Chekov on "Star Trek." Voice and style come with embracing the role and examining yourself to find out what inside of you will make that character come alive. What investment can you make from your own life, from your own experience, that will create a believable personality? I believe that is true for every actor. It's not something that I'm specifically gifted with. Any good actor should be able to expand his horizons. And it's not that you take it from the outside. If you take it from yourself there are times when you're happy. There are times when you feel disillusioned. There are times when you're angry, when you experience a sense of vengeance. All of those experiences are part of us. What an actor does, he or she just picks through it. He just examines who he is, and what in him he can apply, even if it's something that he doesn't use in his everyday life.

When it came to Chekov, he was a spunky guy. He was a guy I never allowed myself to be. That's what you do when you're an actor. Bester on "Babylon 5" was the same thing.

To clarify, I never thought of Bester as a villain. I thought of him as a man who was going to protect his people whatever the cost. In terms of style and voice and making a character come alive and become real I decided to give him a frozen hand. Bester could not use his left hand. It made me, Walter Koenig, feel more like a character of strength, because I had survived this. I had overcome this handicap, and I was still a leader among my people. I appropriated that to make the character stronger.

How do you inhabit a character and make them real as opposed to just playing a role?

I'm a guy with emotions. Frankly, my emotions are right there on the top of my skin. I mean, I could be quiet. I can be withdrawn. But I have access to a lot of feelings when I need them. I don't have to manufacture the feelings that are already there. They're just there. All those feelings and those attitudes are just available to me. I can't paint worth a darn. I have no singing voice. I cannot hold a tune for more than two bars. There are a lot of things that I can't do. I've managed to make my vulnerability something that I can go to when I play different characters.

Conventions like San Diego Comic-Con, C2E2 in Chicago, and the various "Star Trek" and "Star Wars" conventions and other gatherings are now a matter of fact, they are routine. What were those first "Star Trek" conventions like back in the 1970s? Would you ever have imagined that conventions and other fan events would become such big business?

No. And I never imagined that when "Star Trek" was canceled in 1969, that I'd have anything more to do with "Star Trek." Gene Roddenberry called everybody and said, "It's been nice working with you. Hope we can do it again sometime." In response, you say to yourself, "Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. Okay." And you hang up and say, "Now what do I do with the rest of my life?" So, that's pretty much the way I felt. And then when the conventions started, in the middle 1970s, I felt uncomfortable, because the show was five or six years behind me, and people were still lauding the work we had done those years before. I felt, "What about the present?

What about the future? Am I going to have to just rely on something that is now not part of my present existence to get money, to get a sense of self, to feel good about myself?" I felt awkward about that. I felt like we were lauding a ghost. It wasn't until we started doing the movies again that I felt viable. I felt like I was present, and my new work on "Star Trek" was going out to the world again.

During those early conventions there was no precedent for what the rules were, how actors would interact with fans and the like. Did they want to meet you the actor or you the character Chekov? How did you figure it out?

It gets figured out on its own. I do not believe that I had too many preconceptions as to what would happen. I walked into a room with 5,000 people in it, and there was screaming, and I said, "Whoa. What was that about?" After a while, when you do it for over 30 years, you get used to it. I was probably a little nervous that first time at a convention or fan gathering, but very quickly this became my family. And the truth of the matter is you can do no wrong with "Star Trek" unless you were really a jerk. The "Star Trek" fans want to love you. They want to feel like you are part of their family. The "Star Trek" crowd is the easiest crowd I ever worked with.

What was Gene Roddenberry like?

He was not a part of my everyday life. He came on the set maybe once or twice a week. It was always fun to see him. George [Takei] was always pleasant. With the exception of one situation, I always had a congenial relationship with him. I knew there was stuff going on behind closed doors between [William Shatner] and Gene, and [Leonard Nimoy] and Gene, things of that nature.

But in those few years I did the series, at least the first year I did the series, I was just so pleased to be along for the ride. And the fact was, I didn't even have a run of the show contract. I was on a weekly basis. I did not know if I was going to be working on "Star Trek" any given week on a consistent basis. On the last day of an episode we were shooting, they'd hand me the pages for the next week. It was a constant surprise.

The only time I had a problem was we were getting ready to do the TV animated show, and I had been invited to write an episode, which I did. And Gene asked for about five or six rewrites, and I thought it was just me, but I discovered that he did that on the TV series too. There were constant rewrites of all of the episodes that anyone wrote. Gene generally had the final rewrite. At the end, the powers that be were ultimately pleased with what I had done for the animated show.

Then we were at a convention in L.A., before the animated show was going to start, and Dorothy Fontana, who was story editor on the series and an associate producer, made an announcement in front of a room of several hundred people. She announced that cast of the animated show, and I wasn't included. And these people came pouring out of the room when she was done. A bunch of them surrounded me and said, "How do you feel about not being in the animated show?" Well, that was huge. That really upset me. And not to have been told in advance made it worse. I know what happened. One person thought somebody else had told me, and somebody thought somebody else had told me. But still, I was just crushed by it.

We had a panel discussion that afternoon with Gene. We were all in the room, and waiting for the audience to filter in. I turned to him and said, "Gene, I didn't know that I wasn't in the animated show." And he got irritated. He goes, "Well, you know now." That was the only time I ever had a problem with him. But other than that, we got along fine. Gene was a good guy. I always had a good superficial relationship with him.

How did you make peace with portraying an iconic character and now being known mostly for that one role?

I had no problem with it while doing the show because that was my work. I was totally involved with it. As minimal as the part was, I was totally involved in the process of trying to make Chekov come alive. I don't think I ever resented the role. I was just embarrassed by it. It was something that I was doing for a living. Yes, it was helping my career, but I was just playing out the ghost of a role. I went to conventions and fans would tell me how much they liked me as Chekov. I couldn't say, "No, no. Don't say that." But It felt awkward for me.

I only did 12 episodes, but I did some across two seasons. I was a working actor. There was something that I could show. It wasn't sound and fury, signifying nothing. I was a professional. That was fine.

How do I feel about it now? It's taken a toll on me. I've done these little independent projects, and they gave me some sense of hope, and some sense of belonging, and being part of the industry. Still, the acclaim, the acknowledgement for "Star Trek" is disproportionate to what I have accomplished. It's way more than what I've contributed. That does embarrass me. It does make me feel uncomfortable. And at this juncture, I've decided I'm cutting back. I'm not going to do as many appearances. This is the first year that I'm actually dropping the number of conventions that I'm going to do almost by half and try to ease out of this.

Have you thought about your last convention and what your farewell address will be?

Somebody asked me to make this my farewell year. I don't want to do that. Right now, I feel like I want to retreat somewhat from all of this. I might not feel that way in a year. Third, to make a big deal with some type of "farewell year" is making a really big deal out of something that I've already told myself is – regardless of how the fans feel – not that big a deal. I'm not Marlon Brando. I'm not Cary Grant. I'm not any of those people. I don't have that kind of stature.

Shares