Even though it was expected after her disappointing showing on Super Tuesday, it somehow still felt like a gut punch when Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts formally withdrew from the presidential race on Thursday. After giving it some thought, I think I know why: Because this time, there is no other explanation than raw, unvarnished sexism. It just can’t be anything else.

“If Warren was a man, this would be over by now,” is a statement so painfully true that it became a cliché the moment it was first uttered. And yet it somehow failed to capture the scope of the unfairness that greeted Warren on the campaign trail — the way she was held to impossibly high standards, met them, and still saw male competitors who met much lower standards keep scaling past her in the polls.

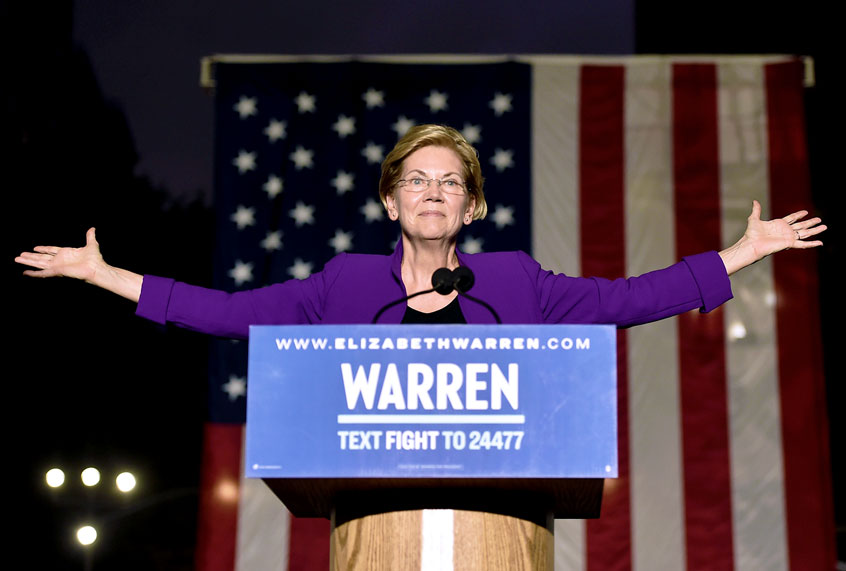

Warren is a slight woman, but always feels like an outsized presence. Her towering intellect, her quick wit, her ability to crush small men like Mike Bloomberg with just her words, her skill at explaining complex ideas simply without dumbing them down, her deep well of compassion that is the thing that drove her into politics in the first place: All of this made her shine so much brighter than her counterparts on the debate stage.

Americans apparently couldn’t see that she is a once-in-a-generation talent and reward her for it with the presidency. That is a shameful blight on us. She wrecked Bloomberg in the debate and, in the process, may well have spared us from seeing a presidential election purchased by a billionaire. We responded as we so often do for women who go above the call of duty: We thanked her for her service and promoted less qualified men above her.

This feels personal to women, and it should. The same forces that pushed Warren out of the race — such as asking her to do the work of figuring out how to finance Bernie Sanders’ Medicare for All plan, and then criticizing her for it while he skated by on generalities — offer a microcosm of how we treat women generally, and the reasons why women work so hard both at home and on the job yet make less money.

Warren’s walk-on song for her campaign rallies was “9 to 5” by Dolly Parton, an upbeat protest anthem the candidate picked because it encapsulated a feminist vision married to her long-standing fight for economic justice. In retrospect, however, the lyrics feel like a dark prophecy:

They just use your mind and they never give you credit

It’s enough to drive you crazy if you let it

9 to 5, for service and devotion

You would think that I would deserve a fat promotion

Want to move ahead but the boss won’t seem to let me

I swear sometimes that man is out to get me!

Men are out to get us. It’s not something my baby-feminist self wanted to believe, but it’s something my 40-something feminist self sees as an irrefutable fact of life.

The same week that Warren was pushed out of the race, the Supreme Court heard the case it clearly plans to use to repeal abortion rights. On the bench was Brett Kavanaugh, who was accused of sexual assault by at least two women and confirmed anyway. He was appointed by President Donald Trump, who, as we all know, likes to “grab them by the pussy.” So yeah, suffice it to say that men have seen women (slowly, slowly) getting a little more power, and their efforts to stop us have not been subtle.

Obviously, the situation is complicated. Some men are feminists who stand by women — although, as recent elections have shown, many liberal men who claim this mantle feel underlying and perhaps unconscious resentment of women who seek equal power. Some women are fierce defenders of the patriarchy. In a system of oppression that is literally thousands of years old, things get complex.

But at the end of the day, all this — the sexual violence, the sexist insults, the stripping of reproductive rights, the tearing down of even the brightest of stars, if they happen to female — comes down to a blunt, grotesque desire to keep women subservient to men.

So yeah, Warren’s defeat is personal for women. And that’s OK. It’s even good, because we’re told not to be angry in the face of so much misogyny, and we need to stay angry very badly. Otherwise, we don’t have a chance.

For me, it’s especially hard. There are a lot of female politicians I admire, including Hillary Clinton and Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi. They’re imperfect and I disagree with them a lot, but it’s hard not to be impressed by the strength to withstand sexism, and often to be sharpened and improved by overcoming it.

But Elizabeth Warren is different. Her, I adore. I tried really hard to remind myself that she was just a politician like any other, but she kept getting in the way of that narrative. I don’t usually give to political campaigns, but in 2011 I broke that rule to give to Warren’s nascent Massachusetts Senate race. I was impressed, like many other people were, by a viral video of her at a campaign event, where she absolutely crushed the ridiculous argument that progressive tax rates are “class warfare.”

“There is nobody in this country who got rich on his own — nobody,” she said to the small group of people at a house party. “You built a factory out there? Good for you. But I want to be clear. You moved your goods to market on the roads the rest of us paid for. You hired workers the rest of us paid to educate. You were safe in your factory because of police forces and fire forces that the rest of us paid for.”

It sounds like common sense, but it’s a kind of common sense almost no one had articulated as concisely or as bluntly in decades — or even since. Even Sanders struggles to frame his economic populism in language that clearly illustrates the interconnected nature of our society and our economy. Only Warren is quite so good at this.

And I think gender clearly plays a role in her sharp understanding of these systems. The way that capitalists render invisible the underpaid, thankless labor they rely on to build their fortunes parallels the way that men have long rendered invisible the amount of unpaid and thankless labor women do to make men’s lives possible: The child care, the housework, the emotional tending, the social-calendar maintenance, the status-boosting. That problem is compounded for women in the workplace, where, as Parton astutely observed, they’re often expected to do the work but not take the credit.

Labor issues and women’s issues are inseparable, and that understanding is what Warren built her career on. It infused her campaign. It’s why so many women feel seen by Warren, who is incapable of talking about “women’s issues” as if they existed in some bubble separate from the economic issues she built her career on.

“Many women saw that Elizabeth Warren was one of them,” Monica Hesse of the Washington Post writes. “It was an impossible tightrope, but she made it look easy; she made most things look easy.”

It helps, of course, that Warren is who she says she is. One really feels that no matter how many offices and accolades she accumulates, she’s still down to earth and that is exceedingly rare in politicians.

Of course she is still an aspirational figure, and especially for me. Her background, growing up lower middle class in Oklahoma, feels very much like mine growing up in Texas. She married at 19, like my mother and my grandmother did. She wasn’t someone who was meant to go to college, to go on to bigger things. But unlike a lot of people, especially of her generation, who didn’t want that life, she … left it.

It’s always going to be a bit of a mystery to me, how Warren got the escape velocity to propel herself out of her first marriage and into an astounding law school career and then into the U.S. Senate. As a journalist who covers politics, I’ve heard her recite the details of that journey a hundred times, but never quite figured out where the moment was when she realized that, oh crap, she was someone very special, someone who, apparently by the sheer force of will, by character and intellect, was able to vault over every single obstacle put in front of women like her to get where she is today.

I have a feeling, since Warren is always going going going, that that moment of reflection might have happened only as recently as Tuesday, at least judging from this quote from her press conference on Thursday: “I stood in that voting booth, and I looked down and I saw my name on the ballot, and I thought, ‘Wow, kiddo, you’re not in Oklahoma anymore.'”

Shit like that sounds hokey in any other politician’s mouth. But dammit, Warren makes me believe. It’s embarrassing. But I believe it. Those who are far from home never quite stop marveling at how far they’ve come.

I’m also jealous. I wanted Warren to stay in the race for a very selfish reason: I wanted to vote for her when the primary came to my state in April. That I can’t do that now crushes me beyond what is frankly reasonable.

I forgive myself for wanting it so badly. Voting for Elizabeth Warren was like making a little wish: A wish for a world where women as bright and kind and hard-working and decent as she is — and there are many forgotten women who are many or all of those things — finally get the recognition that is their due.

But it’s not happening. Not for her, not for her fans, not for those little girls who got a pinky promise that girls can run for president.

I swear, sometimes, those men are out to get us.