Sometimes the only way to connect to your own story is through the soles of your feet. Noé Álvarez grew up working-class in Washington state, the son of Mexican immigrants. A college scholarship offered him a chance at a life beyond the fruit packing plant where his mother worked, but at school he struggled with loneliness and isolation. Then, at 19, he heard about Peace and Dignity Journeys — a series of noncompetitive runs held every four years as "a powerful form of prayer" and to honor first indigenous nations across North, Central and South America. Something clicked, and Álvarez took a leave from school to spend four months running from Canada to Guatemala.

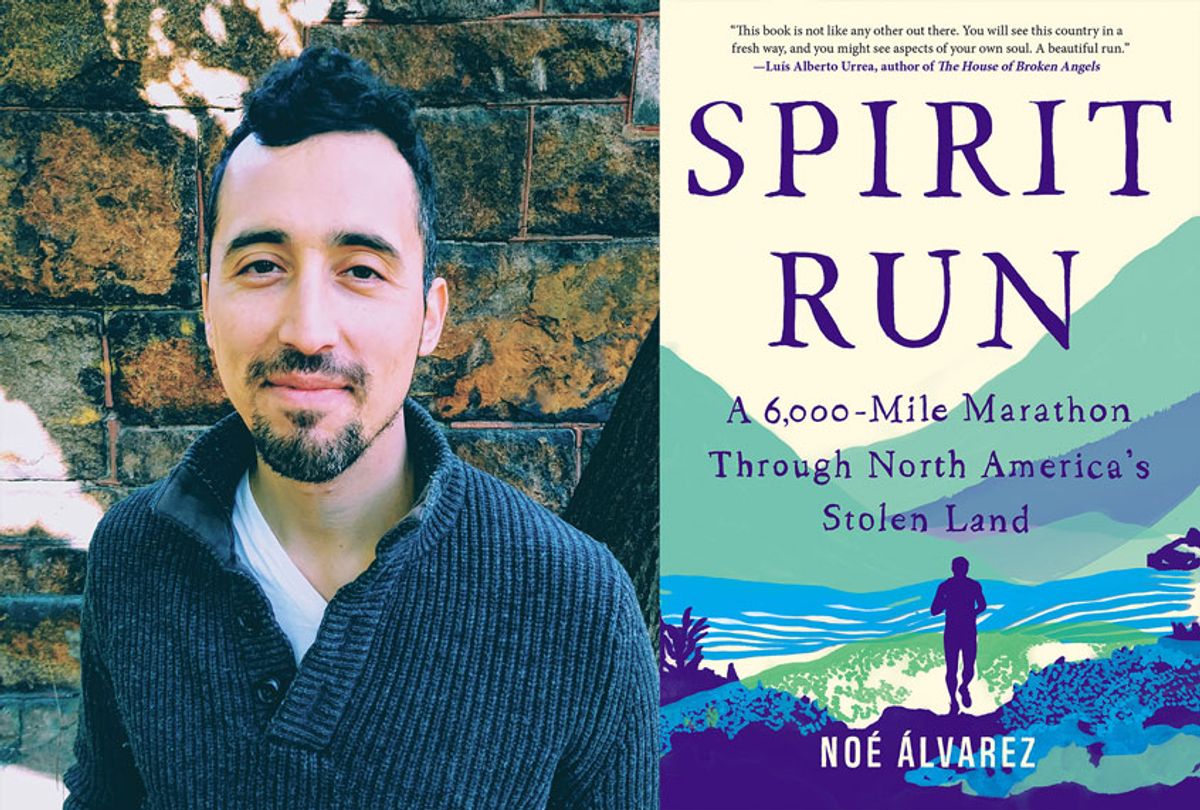

"Spirit Run" (out now from Catapult) is Álvarez's account of that journey, but it's more than another tale of blistered feet and dehydration. It's about the immigrant experience, about the indigenous experience — and finding one's place as a witness when you're neither. Alvarez writes about his family and the other runners on the path, but he's clear he doesn't want to interpret anyone's story but his own. Now, more than 15 years after he laced up his shoes and set out, he talked to Salon via phone from his home in Boston about what he's learned about allyship, and writing a book for his parents in a language not their own.

You've been sitting with this story for so long. Was this something that at the time you thought, "I want to turn this into a book," or was it, "It's 15 years later, and suddenly it's really hitting me that this is a story I want to go back and tell"?

I wanted to process the experience, so it was more trying to figure out how I was going to make sense of this thing that I'm still trying to make sense of. That's the power of living your journey, it's with you all the time.

That's why it [Peace and Dignity Journeys] happens every four years. You have to work at it, so it's this ritual that you have to establish, because we're working on ourselves. And for me that's an ongoing process.

I always had a fear of language. I had bad experiences when I was a small kid, where I got in trouble for speaking Spanish. I was sort of unable to express myself. It was a healing thing for me, and I sat with it because I just wanted to do something for my family. I wanted to convey that experience to them, and I knew that it would never be with words necessarily, like what I told to them in Spanish. Because now my book is written, it's in English — my parents won't be able to read that. Even if it's translated into Spanish, they still don't read very much. So it's got to be something else. My whole way of sharing it with my people and my family, it's on a whole different level.

I had no idea how I wanted to tell the story, or whether I was the right person to tell the story. That's something I'm very aware of. I want to honor people the right way. I've always wanted to honor my dad, my mom. That was a big thing for me. Then when I did this run, I wanted to honor the runners the right way, because the story couldn't be told without them. I'm nothing without them, and the story couldn't have happened without them.

Each person that I write about, that's a whole book in and of itself. I still had to balance, "Is this enough? Does this convey enough? Is this right?" Luckily, I'm still in touch with them, and got their permission and went through those rituals. I don't know how it came about, but it was inside of me for many, many years.

I used to do social work with youth and I just needed to process things. I took a community college writing class in Seattle, and I was always going back to the same theme. One of my professors called it out and said, "There's something here. You should do something more focused about that."

It turned out that I wanted to talk about the run. I think I always wanted to, I just didn't know what that looked like. I didn't have a model for that. It's a story about immigration. It's about a run. I wanted to articulate the spirituality and emotion that my parents didn't convey, at least with words. I was trying to find new ways of speaking, of seeing my world, and I didn't have any models for it. I just wanted to be careful about how I put that out there.

One of the central themes of this book is the stickiness of being an ally, and what happens when you enter someone else's space. You were there because you want to be an ally, but you were also running the risk of being unwelcome, and sitting with that discomfort of being unwelcome in certain spaces.

Because it's been so long since you experienced this, do you think that has changed, because more of us are trying to figure out our spaces as allies, in a way that maybe we didn't before?

I think it is changing, because there are a a lot of private aspects to ceremony, but there are also a lot of public aspects to it. When we did the run, you know there's a lot of privacy around certain protocols and rituals that we were doing, to respect of the territories that we were in.

But it's also very public. For instance, we run out in the streets. We're trying to get attention. I think, given our times, given the climate of things, we are screaming. We're asking for people to look and pay attention. So we're asking for allyship, right? But of course, what it means to be indigenous, what it means to be Latino, what it means to be working class, is very specific in individual people. The book I wrote is what the run was for me. Everyone else who would write this book would probably tell a slightly different story.

That is exactly what Peace and Dignity is. It's complex; it's messy. The thing that I learned about allyship is that it's really hard work, and that you have to really put in the mileage to make relations function. You have to earn your place with people. I write about sharing in the sweat, about being family to everyone, just making yourself vulnerable to people.

For me, I showed up, and as you read, it was complicated. I wasn't immediately welcomed. But that's a reality that I understood. Words weren't going to make that situation better. I knew that, at least at the get-go, and so I had to earn it.

I was pitching in, working, volunteering, taking on loads, volunteering for mileage. I wanted to show that I was putting in the work, that I was committed to learning, and that I was very respectful of people's protocol of stepping aside. I still do that, I still don't consider myself an authority in anything, and a lot of things barely.

We wouldn't be doing this if you didn't want people to see and to participate. And it invites people of all walks of life.That is allyship, and it is going to be very sticky, but that's what I write about. There are people out there like me, who might benefit from the story that shows, look, this is complex and it's okay. We're working at it. And the way that we're working at it is through running. That's our medium for connection, for prayer, spirituality.

I love the phrase in the book, that the run is "the longest prayer in the world." It's also important for any of us, because all of us are outsiders in one space or another, and it was important for you to show, "Look, there were people in the run who were not great to me at all. And maybe it was hard, but I learned something." Sometimes as an outsider you have to be open to that and humbled to that, to push through your discomfort anyway.

That's okay to feel like an outsider, but I think that shouldn't stop us. I think that should motivate us to tread carefully, but to still make that effort. Because there's beauty in difference. Just because something scares me, something is looking different or I don't get it, shouldn't stop me from trying to build a community around that.

That was part of the process of writing this. I came in as an outsider and I was angry about some things, and I did want to run on my own terms. Those complex relationships that I did have on the run, I didn't want to say, "Oh, it was them." I wanted to be, "Where was I at fault?" I was having to confront the reality that I was a problem in my own way and therefore did not connect better in the way I would have liked.

I went in there, I was really messed up. I didn't really fully recognize that other people were just messed up as me. You don't see yourself in the problem sometimes, until you step away from it. I tell people that running was a healing act in itself. Writing it was another healing phase, and then now talking about it is a different healing.

You continue to look back at your story, and you continue to see the complexity of it, and that it's always teaching. When I still run, I still think back to those moments, and it continues to redefine who I am. I'm the first to tell you that I'm flawed and complicated and full of mistakes, and that's what I try to convey on the run itself. It's like, "I'm working at it. That's all I can do." I'm trying to work on it, bringing attention to other people's stories on the run, by weaving them in, and hopefully it brings attention to their communities.

I hope to plug back into their communities and see them in Canada again and organize something in California with the runners, bring attention to their community. That's what I want. That's how I envision the tours that I'm on. I want to create spaces for people who don't necessarily have them, or where society doesn't allow them. It's a conversation starter. This is how I want this book to be conveyed.

Going back and looking at yourself at a different point in your life, that can be a real reckoning. When you're writing about the person you were at 19, how do you then create the character? Who is this 19-year-old who's about to drop out of college for a while? How do you not aggrandize him, but also keep him interesting, as the protagonist?

I definitely wasn't ready to tell a story at 19. It's a lifelong process to make meaning out of it. I talked to some of the runners and I checked in with them too. I said, "Look, this is what I remember about you, this time. Do you remember that?" They shared information with me that I had blocked out. Then I just got to writing them. I took it by scene by scene, just getting it down and figuring it out later, not thinking about the bigger picture because there were so many components to it. Runner's story, my story, dad's story, mom's story. It's a day by day thing. That's how the run was.

But these scenes were very powerful and that was enough at the time. I still think similarly or feel similarly when I was 19 years old. I'm still restless, I'm still questioning things that I was questioning back then. I'm still pressed by, and I'm still making the same sort of inquiries that I was when I was 19. I still feel very curious. I still need to learn. I'm still just naive in a lot of ways. It's been a beautiful process, trying to put words to emotion and spirit. I think it's a good way to be. It's a good way to think about how you've grown and things that you're still needing to work on. It was hard. It's hard to say, "Oh, how was I as a kid?" But in a lot of ways, I'm still a kid.

Shares