You can change lives, and the only thing you need to do is cook dinner.

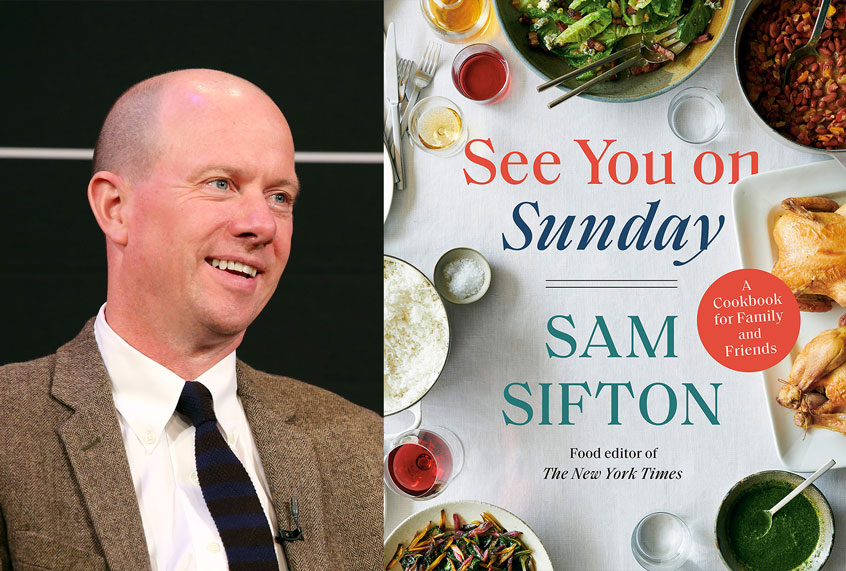

There’s a line in New York Times food editor Sam Sifton’s latest cookbook that says, “People that are lonely, feed them.”

“I don’t think we like to admit it, but I think people are lonely,” the author of “See You on Sunday” told Salon in a recent interview. “Invite them in, feed them and they’re going to have a better time. And you’re going to feel better for having given them that gift.”

Sifton is on a quest to bring Sunday suppers to America. And in the era of Trump, the call to gather around the table with family and friends seems all the more relevant. The British have a rich tradition of Sunday suppers, with dinner often being built around a big roast. But we don’t have an equivalent in America. And instead of sitting at the dinner table, we’re often sitting on the couch in front of a screen or two. What we should be doing is connecting over food.

The beauty of a Sunday supper is that it’s much cheaper to host than a dinner party, and anyone can do it no matter the size of your kitchen. It doesn’t matter if you have a large family or a friend group, because the invitation is an open one. You just have to remember one important rule. Instead of saying goodbye, go with this: “See you on Sunday.”

When Sifton recently appeared on “Salon Talks,” he taught us everything we need to know about starting a Sunday Supper, and he revealed the reason behind why he started hosting them. To learn the answers, you can watch my full interview with Sam Sifton here, or read a Q&A of our conversation below.

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

“See You on Sunday.” This title was born out of a tradition that started many years ago. Can you tell us how it all began?

Absolutely. I have for a long time been a proponent of Thanksgiving. My last book was all about Thanksgiving and how to cook it well. And what I realized over the course of many, many years of preparing Thanksgiving is that I really like the sense of that day, and I wanted to bring it into our lives on a more regular basis. So I started cooking Thanksgiving more often — not literal Thanksgiving with turkey and mashed potatoes, but gathering friends and family together. And it became a ritual — a very exciting ritual — and one that my family shares with cultures all over the world. Still, like Thanksgiving, it’s scary to a lot of people. I wrote this book to offer confidence to people that they can do it. It’s not that hard. It just takes doing it, and then doing it again.

How do you define “Sunday supper”?

Well, first of all, it doesn’t have to happen on a Sunday. You can have a “Sunday supper” on a Thursday night if Thursdays are the night you want to do it. It is a regular dinner — not a dinner party. A regular dinner with your close pals, or your family or whatever iteration of people you want. It should be able to grow and shrink as people are around or not around. Strangers should always be welcome, and it requires a cooking that allows you to stretch things a little bit. That’s why I have a lot of pots of stuff — a big vegetable stew or a big beef stew — so that if 10 people come instead of eight, there’s still food for them. So, what defines it? “We’re having it. Come on by.”

What makes a Sunday supper different from a regular dinner party?

There’s a sort of expectation for a dinner party — that the conversation is going to be sparkling, that there’s going to be excellent wine, that you might get a hook-up situation going. There’s social engineering that goes into creating a great dinner party, and I love going to a great dinner party. But a dinner party is different from a family meal. This is a family meal where the family is more broadly defined than the dictionary would have it. It’s your neighbors, it’s your friends and we’re not there to show off. We’re not there to hook up. Where there, because this is what do on Thursday nights, Friday nights, Saturday nights, Sunday nights. And I think that being intentional about that communicates to the people who come what their behavior ought to be like.

One thing you touched on is there is a common equivalent of a Sunday supper in other cultures. For example, I was in London this past spring, and I went to a roast at a pub. When I used to live in Argentina, when I was studying there, we had asados, or grill-outs. Why aren’t Sunday suppers as big here?

Because people haven’t read my book yet, Joe. The tradition of the Sunday roast in England, the tradition of the asado in South America, these are the things that we’re following along. This is what I want to bring to the American kitchen — to the American dinner table. The ability to gather just because and to have a great time. Now I love a Sunday roast, but if you do that every week for a while, you’re going to run out of bank pretty quickly. It’s an expensive cut of meat. So maybe you don’t want to do that all the time, but I do endorse the regularity of it,. And if you can cook outside on a parilla or whatever, great. Do it.

I understand there are some social benefits to this.

I’m not a doctor, but I play one on web TV, and the social scientists who I’ve spoken to about this do say that this sort of regular gathering with family and friends increases what they call the term of art as life satisfaction. And it makes you feel better, makes the people who come feel better. There’s a line in this book, where I say, “People that are lonely, feed them.” And I think that’s true. I don’t think we like to admit it, but I think people are lonely. Invite them in, feed them and they’re going to have a better time. And you’re going to feel better for having given them that gift. And in a way, I feel like this is a good tradition to start, because I feel we’re so digitally plugged in now.

We don’t often even enjoy a dinner at the table at home with our nuclear family these days.

That’s true. You could have three or four people sitting around a table eating top ramen and checking their feeds, and that’s depressing. It’s also a fact of life. So if we can — again I’ll use that word intentional — if we can be intentional about saying, “Listen, one night a week we’re going to gather, or they’re going to be no phones at the table. No screens involved. We’re not watching the game.” What we’re doing is just gathering, and the presence of food, and drinking and sharing stories among one another. I think that’s a positive thing.

If I’m going to do it, how do I get started?

Well, it depends. You can choose your lane. I wouldn’t start with the full Thanksgiving with 15 people. I’d start with a smaller group and say, “Well, what can I do for the smaller group? I’m going to roast a chicken. I’m going to make a big pot of gumbo. I’m going to have a giant salad. We’re going to roast some vegetables.” Something that’s big. And put that on the table with a bunch of rice, and see how it goes. And the most important thing is to say at the end, “I’ll see you next Sunday.” Because it doesn’t happen in that one meal. It accrues over time. Once you’re a month, six months into it, you will realize, “Wow, that’s a cool thing that we’re doing.”

In terms of food, less is actually more, correct? That was one thing that I learned from reading the book.

Absolutely. I think that this idea that you’re going to create some frilly dish that looks like it could be served at a chic downtown restaurant, though chic downtown restaurants are now trying to make their food look like home cooked food. But the idea is not to be fancy. The idea is to provide sustenance. And that doesn’t mean that it needs to be bland. It shouldn’t be bland. That doesn’t mean that it needs to be boring. It shouldn’t be boring, but it doesn’t need to be over the top. This is not a time for an ambush. This is a time for really well cooked roast chicken, and some perfectly done rice and a nice conversation.

And you can even skip dessert, correct? You give us permission not to bake. We can throw a little ice cream or a little slice of fruit.

Yes, I think there’s nothing wrong with that. I think, in fact, that’s to be cherished — if you’re not a baker. Now, I hope that there are going to be a lot of people who read and use this book who are bakers, who are pastry-minded, because what could be better than an apple pie at the end of one of these meals? And there is a recipe for apple pie.

Or the cobbler . . .

Or those cobblers or the crumbles. When it comes to cooks, I have found in my work at The Times that the world breaks down into savory and sweet. I’m more of a savory cook than I am a sweet cook, and I like the idea that I can say to my guests: “Yes, bring a pie.” Or, “Yes, bring a watermelon.” Or, “Yes, bring a pile of beautiful navel oranges. We’ll get them in the fridge.” There’s nothing better than a cold orange at the end of a hot meal, and it elevates the whole thing without being fancy about it.

You also talk about setting up the home kitchen in the book. What are the essential tools for hosting a Sunday supper?

I think that you need fewer tools than you imagine, but you do need some tools. If you ramp this up, you’re definitely going to need them. So I think having a big Dutch oven or a big heavy bottom pot is going to come in handy both for pasta water and rice but also for stews and just large format protein mixtures.

I think that having a bunch of sheet pans — like those half sheet pans — really comes in handy for all measure of things. My friend Melissa Clark with whom I work at the New York Times has a great line about sheet pans where she says, “If you have one, you need two. If you have two, you made three.” You can use them for cleanup, you can use them for cooking, you can use them sometimes for serving — and that’s key.

Having a good chef’s knife is good. Having a colander is important. Having a cutting board, a bunch of bar towels or dish towels is helpful. And big sauté pan, that would be helpful. I like having a cast iron pan, but now we’re going over the top. You need a knife, you need a cutting board, you need a couple of pots and pans and that’s about it just to get started.

What I’m taking away from that is that anyone can do it —

Anyone can do it.

You don’t want to have to have infinite resources to get this going.

No, I spent a long time cooking for this book in a decrepit parish hall kitchen in a church in Brooklyn, where the most reliable item we had was a huge rice cooker — like a rice machine. I love a rice cooker.

My rice cooker is one of my favorite things in the kitchen.

Isn’t it?

My grandmother is from Mexico, and she taught me how to make rice in a pot. My college roommate was half Filipino. He introduced me to the rice cooker, and I haven’t looked back, because you get almost perfect rice every time.

I’d go further — you get perfect rice every time. Once you learn your rice cooker and its moods, you’re going to get a perfect outcome every time. And then that’s something you don’t even have to think about.

I like to say that we all cook to feed something. Cooking connects me to my Mexican American culture and some of my earliest childhood memories with my grandmother in the kitchen and my mom who passed away a few years ago. What are you feeding when you cook?

That’s a great question. I’m sorry for your loss. My mom died recently, as well, and it does rock you in the kitchen a little bit if your mother was a cook. And my mother was a cook. I think what I’m trying to do is feed others. That sounds banal, but let’s unpack it a little bit and make it more intense than it sounds. I see cooking for others as a service. I don’t know if it’s a religious service, or a spiritual service or ritualistic service. But I know that by gathering ingredients, and preparing them and serving them with a modicum of implied, if not explicit love, I’m giving something of myself to other people that I think they can accept in kind. And their acceptance is important to me, and I think makes our family and friendship dynamics work better.

I agree. When people come over for dinner at my place, they know that they’re probably going to have Mexican. So I love your choice to include taco night in the book. I feel like I’m not only sharing a part of my culture, but I’m feeding them and sharing a part of myself. And that experience of eating together is really something magical.

Yes, it’s interesting for me as a food journalist. As someone who reports on food, I can’t claim a particular cultural background that’s going to inform my cooking beyond Swamp Yankee, Scots-Irish, bad white people thing. And there’s some good food in that. But as a reporter, I’ve spent so much time finding great things to eat in different places and then bringing those back and repackaging them through my own hacks and miseries into something that is really American, I guess. And then putting it out there — it makes me so happy.

You have a lot of food savvy friends, some of whom you write about in the book. And I know we have one friend in particular. Can you talk a little bit about how your friends shaped this book and the Sunday supper experience?

My friends, who are very important to me, are at the heart of this, either as people who shared my table or as people who brought me along. A very proud alum of Salon, Manny Howard, is one of them. And we’ve been cooking together — cooking some form of this meal — for like 25 or 30 years. And his towering ambition for a lot of meals has informed my cooking in really interesting ways. There’s a whole chapter in here about a style of a dinner that I got from him, which involved literally shucking oysters, frying potatoes and then frying hotdogs after the potatoes. And that’s it. That plus beer, and you have a wonderful day. It’s not precisely a Sunday suffer, but it’s a heck of a way to spend a day.

I need to hear the story about Manny making paella.

Well, those of you in the Salon audience who know Manny Howard know him to be — as I say, he has towering ambition in the kitchen. And the first time he made paella on the grill, I think we ate close to midnight. People arrived around 5:00 p.m., and we ate close to midnight. And there were a lot of trains running and a lot of different directions. People were scared, frankly. But the result was so magical and great that I thought, there’s got to be a way to capture this lightning in a bottle so that anybody can do this. Not just Manny — so that I can do this. And so I broke down the evening, and then put it back together and tried to speed it up in certain ways. And the result was the recipe for grilled paella that’s in the book that won’t have you eating at midnight. It’ll have you eating at a normal time, but with no less delicious a result.