The coronavirus pandemic is a present-day dystopia. Unfortunately, it is not the stuff of a science fiction novel set in the near future or an alternate reality. If not stopped, this pandemic threatens to become a new type of normal, one where the pain and misery are chronic, and therefore gradually seen as acceptable. The damage is ongoing, and will only get worse with time.

This pandemic has already killed more than 70,000 people in the United States. A million or more are infected. The Trump administration — in what may well be an intentional undercount — now reportedly projects that by June 1 at least 3,000 people will die of COVID-19 every day.

The economic devastation has also been significant: At least 20 percent of Americans are out of work. Trillions of dollars in wealth and income have also been destroyed. The harm caused by this catastrophe will be intergenerational in ways not yet understood or imagined.

But for some people the coronavirus pandemic is a type of utopian dream. Many right-wing Christians see the combination of the pandemic and President Trump as good things. Why? Because in their mythology these events are harbingers of the apocalyptic "end times," a titanic battle between good and evil during which true Christians who are "saved" will be raptured away to paradise. Writing at Rolling Stone, Bob Moser describes the power of this deranged fantasy over the Trump administration:

While the media typically just uses the euphemism "Christian" to describe such beliefs, these folks are Christian nationalists, who view the second coming of Christ as an event in which America will play a leading role, thanks to its founding as a "Christian" nation and its Judeo-Christian principles. They're also known as Rapture Christians, thanks to their conviction that before things start to get really ugly on the earth, with God-sent wars and plagues far worse than COVID-19, they'll be wafted up to heaven en masse, to live in eternal peace, bliss, and moral superiority while everyone else — including lesser Christians — suffers years' worth of unspeakably gruesome torments prior to the final, earth-destroying battle between Warrior Jesus and Satan at Armageddon, and the Final Judgment in which Jews and others who refuse to convert are condemned to eternal torture in hell.... Now, their pagan king is leading us through an actual Biblical-sized plague — with the guidance of End-Time Christians.

As a class, the gangster capitalist plutocrats view the coronavirus pandemic as another opportunity to make money from human misery and expand their power over America and the world.

Many neo-fascists and other members of the Global Right are "accelerationists" who want to bring about the destruction of multiracial democracy in North America and Europe so that they can rebuild Western society as a white-only or white-dominated autocracy. Nonwhite people, Jews, Muslims and other "undesirables" will be killed, enslaved or exiled through an apocalyptic "race war."

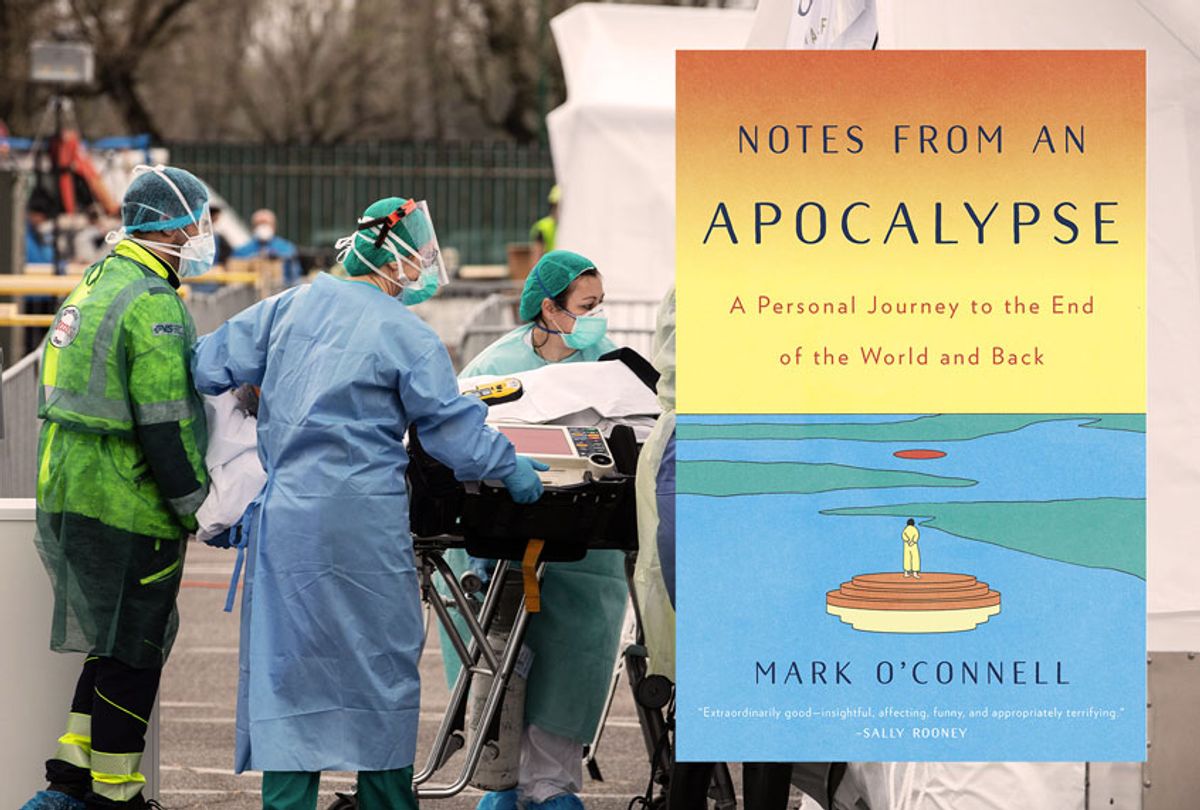

Mark O'Connell is the author of the new book "Notes From an Apocalypse: A Personal Journey to the End of the World and Back." His essays and other writing have been featured in the New York Times Magazine and the Guardian.

In our conversation, O'Connell reflects on the strangeness of publishing a book about the end of the world just as the world is confronting the coronavirus pandemic. He explains how disasters are an opportunity for right-wing extremists, as well as plutocrats and oligarchs, to advance their antisocial agenda — and how such people plan to survive the apocalypse. O'Connell also argues that this pandemic may provide an opportunity for the best of humanity to assert itself, rather than devolving into barbarism as many doomsday preppers, survivalists, one-percenters and others have both predicted and, perhaps, hoped.

Given the coronavirus pandemic, your new book is either very well-timed or very horribly timed.

I suppose that it is both. But I can't really decide. I was being interviewed recently and I was asked if "Notes From an Apocalypse" is prophetic. The book is actually the exact opposite. The timing is sheer coincidence. The prospect of a pandemic coinciding with the launch of my book seemed so far-fetched. Who could have predicted it? There is a great deal of dramatic irony around the timing for my book in a moment people are talking about nothing other than how apocalyptic everything feels.

Moreover, the prospect that the coronavirus pandemic could just become part of how children normally experience reality is quite sobering for me. I hope that these children, when they are adults, do not look back on this moment with the coronavirus as that singular event where everything went to hell. I hope they remember it as some type of weird, strange interlude that we all had to live through.

The apocalypse is never the end of the world. It is an idea that people reach for and use as a way to make sense of incomprehensible and challenging times. The apocalypse is a way to manage uncertainty and chaos and sudden change. Those are the times when the idea of the apocalypse rears its head, and I think this moment with the pandemic is definitely one of those moments.

In making sense of this moment, it's very important to highlight how one person's dystopia or apocalypse is another's utopia and dream. Some people have been waiting for a disaster such as the coronavirus pandemic, in order to remake the world.

One of the things that has kept me going throughout this uniquely horrible experience is the idea that things are going to change in society because of this, and that those changes might be beneficial for a large number of people. The truths that are revealed by a global catastrophe cannot be easily ignored. The catastrophe shines a light on how societies are fundamentally structured. There will be those people who want to create positive change and there will be bad actors who are using the pandemic to advance a less hopeful and more negative vision of the future and society.

One of the scariest things about the coronavirus pandemic is that there are people, right now, for whom this disaster is an opportunity.

The coronavirus and its destruction strike me as a metaphor for Trumpism. You live in Britain. Is the coronavirus viewed as a metaphor for Brexit in the U.K. and Europe more broadly?

In terms of metaphor, for some time here in the United Kingdom and Europe everything seemed to present itself as a stand-in for Brexit. But I do not see the coronavirus as a metaphor for anything. Yes, there are ways in which it absolutely reveals so much about the way we live in the West and elsewhere at this moment in history. But how can the coronavirus pandemic be a metaphor for something else when it is the dominant subject of conversation — really the only thing that most people are talking about?

You are correct to say that the virus itself, in a U.S. context, is a huge society-wide problem. But the virus is not the central, fundamental core problem in your country. The problem is the radical inequalities in your society, the insane approach to health care, Trumpism and other issues which make the coronavirus' impact much worse in your country than in most others.

In philosopher Fredric Jameson's book "Archaeologies of the Future," he argues that science fiction may focus on the future, but in fact all writing about the future is really an exploration of the present. How do you negotiate that tension?

In a way both of my books have been about "the future." "To Be a Machine" is about people who are obsessed with a fantasy version of the future. "Notes From an Apocalypse" is also about some version of the future. But I am not interested in making predictions about what life will be like in the future, or thinking about various permutations of technology or politics, or how are we going to live in the year 2065 or what have you. That topic is not interesting to me.

I am interested in the present and the near past. For me the future is really a way to think through the complexities of the present. The ways that we imagine the future always have as much to do with the past as they do with anything else. The future is not a real thing. It is just an idea.

In terms of the way crises present a type of opportunity for some people, how are plutocrats and mega-rich individuals like Peter Thiel preparing for the apocalypse?

For me, Peter Thiel almost operates as a metaphor, a way for me to invest all of my anxieties and loathing about the extreme manifestations of capitalism. In that way, Peter Thiel is a kind of gift that just keeps on giving. A good portion of my first book, "To Be a Machine," focuses on Peter Thiel's quest for eternal life and the various companies he's investing in as a way of accomplishing that goal.

In my new book, Thiel is a metaphor for the most horrifying aspects of capitalism, the moral void at the heart of the whole ideology and system. The way that he imagines surviving the collapse of civilization is extremely interesting insofar as it's a way of thinking about how, in the present, with late-stage capitalism there is an increasing drift away from any kind of investment in democracy. What Thiel represents is the idea of the future as belonging to a very small number of extremely intelligent, far-sighted, radically self-interested individuals.

One of the responses to the coronavirus pandemic and economic collapse here in the United States has been the suggestion by Donald Trump and his followers that elderly and vulnerable people should be willing to die for "the economy." It's almost a form of human sacrifice.

Civilizations fall. And they fall quite suddenly. In fact, some of the most elaborate and sophisticated former civilizations practiced some type of human sacrifice as central to their culture. A classic example would be the Aztecs. They were convinced that human sacrifice was necessary for the continuation of their way of life. Such cultures genuinely believed that they had to kill to appease the gods and to ensure a good harvest or some other type of prosperity.

Now, it just so happens that they were wrong. Modern society has convinced its subjects that we have moved beyond such behavior. Human sacrifice seems too barbaric to us at present. But in reality, our own modern civilizations are based on human sacrifice in various forms.

The rich are building luxury bunkers to survive the "end of days" and to ensure their social and political power in the future. What does that reveal about Western society and culture?

Those bunkers are a classic, overblown, extreme metaphor for capitalism in the present, not in some imagined future. The rich are building luxury survival bunkers with private cinemas, DNA vaults, wine cellars and other lavish ways of surviving the end of the world. As the saying goes, "It is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism."

What do these luxury bunkers reveal about how the global one percent and other oligarchs imagine society? Do they simply reject the obligations and responsibilities that human beings should have to one another?

Whether it is doomsday preppers who are stockpiling guns and freeze-drying food, or billionaires buying chunks of the South Island in New Zealand, the approach is to look after yourself first and survive at the cost of other people, or survive outside of the context of other people. In all these cases it is civilization as both an idea and structure that is considered a very fragile thing. From their point of view, society is a weak construct, a very thin layer of societal norms which hangs over an abyss of chaos and violence.

The preppers, as with the very rich who are building these luxury bunkers, have a sense that people are going to quickly revert to some type of animalistic savagery once a severe enough crisis comes along. This idea animates so many of these right-wing apocalyptic thinkers. It is capitalism to the extreme. The heavily fortified, luxurious bunker is just a logical conclusion of the gated community and of capitalism itself.

But such a conclusion is also wrong. During the pandemic, from what I have been seeing, people have mostly been pulling together. Community and society are much more resilient than we have been led to believe. That is something which is not accounted for in the worldview of the apocalyptic people, the preppers and so on. For them, this is not what is supposed to happen. They believed that the pandemic was supposed to create a state of mass civil unrest.

Shares