A scientific study released in March found that a parasitic microorganism which preys on salmon does not rely on oxygen to produce the energy needed to survive. The discovery upends the common sense about what defines animal life.

The article, which was published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences and based on a study led by Dayana Yahalomi from Tel Aviv University, revealed that the microorganism “has lost its mitochondrial genome,” and hence does not respirate in the manner that all other animal life does.

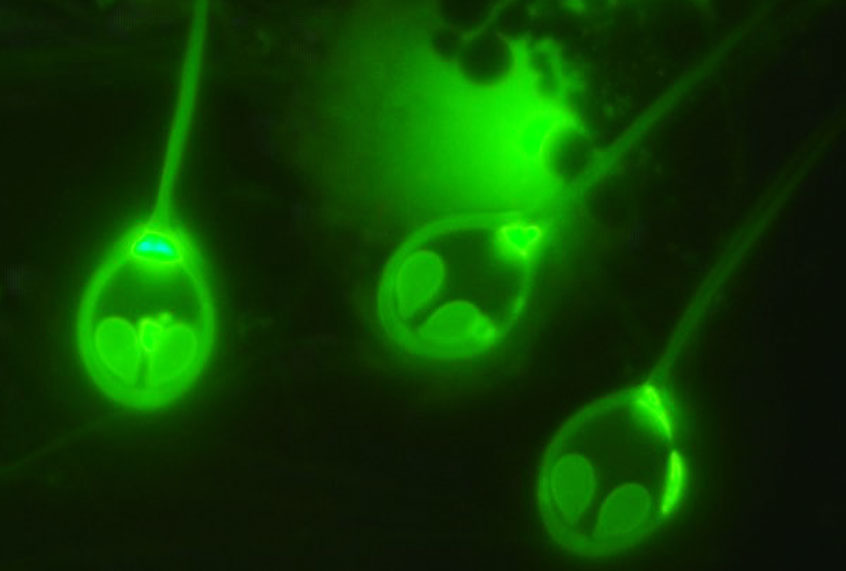

“The myxozoan cells retain structures deemed mitochondrion-related organelles, but have lost genes related to aerobic respiration and mitochondrial genome replication,” the article explained. “Our discovery shows that aerobic respiration, one of the most important metabolic pathways, is not ubiquitous among animals.” The scientists uncovered this using deep sequencing and fluorescence microscopy.

The animal that is able to perform this improbable feat, the Henneguya salminicola, is part of a phylum called cnidarians, which also includes jellyfish, anemones and corals. It spends its entire life cycle inside of salmon and is able to survive so efficiently off of its host that it does not need to consume oxygen on its own.

“They have lost their tissue, their nerve cells, their muscles, everything,” evolutionary biologist and study co-author Dorothée Huchon, who works at Tel Aviv University, told Live Science. “And now we find they have lost their ability to breathe.”

The parasite, though hardly pleasing from an aesthetic standpoint, is nevertheless interesting as a subject for study, particularly in terms of understanding why they no longer need to breathe.

“Myxozoans have gone through outstanding morphological and genomic simplifications during their adaptation to parasitism from a free-living cnidarian ancestor,” the study noted, referring to the aquatic and parasitic subphylum. “It is remarkable that these myxozoan simplifications do not appear to be ancestral, but rather the result of secondary losses. Here we show that at least one myxozoan species has lost a core animal feature: the genetic basis for aerobic respiration in its mitochondria.”

“As a highly diverse group with >2,400 species, which inhabit marine, freshwater, and even terrestrial environments, evolutionary loss and simplification has clearly been a successful strategy for Myxozoa, which shows that less is more,” the paper’s coauthors concluded.

Scientists do not believe that Henneguya salminicola are dangerous to humans when consumed while eating salmon.

“Although the cysts in the flesh are visually unappealing when present in large numbers, there are no human health concerns associated with Henneguya,” explained the Alaska Department of Fish and Game in a 2008 booklet called “Common Diseases of Wild and Cultures Fishes in Alaska.” The department also pointed out that “fish infected with Henneguya have numerous white pansporoblasts (cysts) in the target tissues that are filled with the spores.”

The department also explained that “the spores of this parasite occur in the muscle and under the skin of Pacific salmon causing a condition known as ‘milky flesh’ disease because of the creamy white fluid containing spores that oozes from the cysts (pansporoblasts) during filleting. It is also known as ‘tapioca’ disease from the many small round spore containing cysts in the flesh.”

Fish parasites have been in the news lately. A study in Global Change Biology from March found that fish are infected with 283 times more parasitic worms than they were 40 years ago; specifically, the parasitic nematodes in the genus Anisakis are now rife in seafood, studies find. Anisakis begins its life cycle by appearing in the intestines of marine mammals, which then defecate them out to infect krill, fish and small crustaceans in their larval stages, where they appear as cysts in their muscle tissue. People can consume them if they eat fish that is raw, smoked or undercooked, and although the parasites cannot survive in human intestines, they can still trigger an immune response that results in nausea, vomiting and diarrhea.