Svenja O’Donnell’s debut book “Inge’s War” retraces her German grandmother Inge’s story of survival on the wrong side of World War 2. Brinn Black spent years trying to find out what happened to her German grandmother Erna’s family, whom she lost track of in the last weeks of the war.

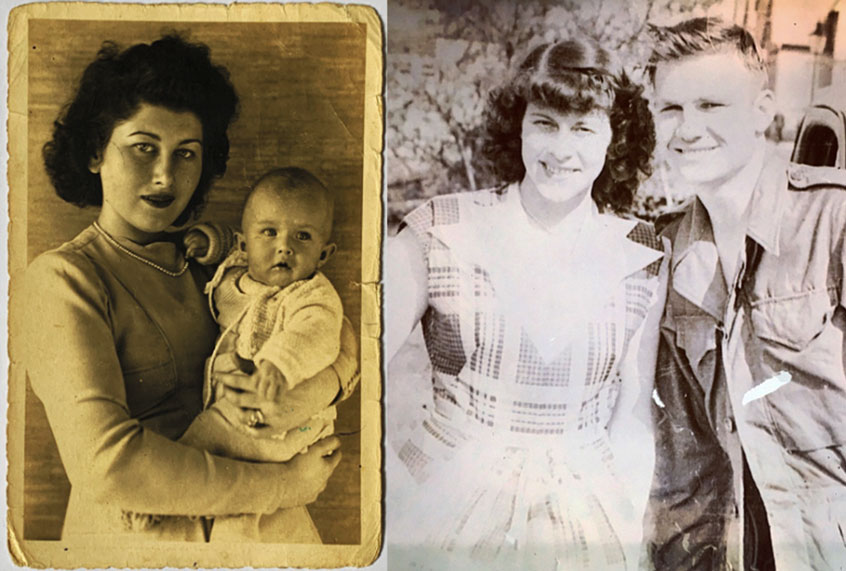

Their friendship started when O’Donnell, who was researching her grandmother’s past, found a faded photograph in the attic of her family home in France. She posted it on Twitter with the caption, “My grandmother Inge holding my mother in Königsberg, 1943.” Black, a singer/songwriter in Nashville, Tennessee, was the first to reply: “My Omi [German for Grandma] was from there too. I’ve been trying to find out what happened to her family.”

Königsberg, the regional capital of East Prussia, was once Germany’s easternmost point. At the end of the war, it became the Soviet exclave of Kaliningrad, and remains Russian to this day. O’Donnell and Black soon discovered they shared more than the strange kinship of a forgotten land.

O’Donnell’s grandmother Inge and Black’s grandmother Erna were born a year and a few blocks apart. They shared the same upper middle-class background. Both fled the Red Army’s advance in East Prussia in early 1945. Erna never saw her family again; Inge’s relationship with her daughter’s father was shattered by her experiences in those months at the end of the war. Both rebuilt their lives, turning their backs on a past too painful to remember.

For granddaughters O’Donnell and Black, finding out the truth had become almost an obsession. As independent women who had been raised to speak out, they were determined to release their grandmothers’ stories from decades of silence.

They spoke on Zoom about the importance of memory, and how an inheritance of loss and survival endures through generations.

Svenja O’Donnell: I remember being struck, when we first met, by the fact that you, a stranger on the other side of the world, not only shared my family background, which is one that very few people do. But you also understood my almost obsessive need to find answers in a decades-old past, and to tell my grandmother’s story.

Our sense of history is often shaped by the narratives of men, soldiers and politicians. The experiences of women at that time are rarely shared. Their lives, away from the front line, are often dismissed as not worthy of much scrutiny. And yet both our grandmothers lived through extraordinary times, the emotional scars of which they bore for decades.

I’m struck by the fact that neither of them spoke about it. My grandmother Inge was an aloof woman who led what I’d always thought of as a rather dull life. It’s not until I went to Kaliningrad, when I was working as a foreign correspondent in Russia, that things changed between us. My going to her old homeland unlocked something in her. And still, it took her years to finally confide in me the secrets she had kept for most of her life.

I wonder if trying to put that past behind them was the only way they could survive?

Brinn Black: Omi never talked about that time. I think some of that was due to shame. The shame of not wanting her kids to see her as a victim. The shame of being German after the war.

So she did not confide in her kids. The people she chose to occasionally speak to were always one step removed, like my mom — her son’s wife. [My mother] spoke some German and I guess that helped create a bond. [Omi] never spoke to my Dad about it. She probably saw too much of her DNA in him and in his troubles to really talk to him about it.

Erna had been part of a civilian draft to work on the railways during the war (NB: women were drafted in to do the work because men of working age were called to the front) and had managed to get back to Königsberg in April 1945. She was looking for her mom and younger brother and sister, but found out they had already fled. She managed to escape the Soviet advance by smuggling herself in with the retreating troops. Her dad, who had been conscripted into the army and was somewhere on the Eastern front, had not been heard from since January. She never saw any of them again, or ever found out what happened to them.

She was always a very active person until she developed a brain tumor. It was very fast, two weeks. The tumor did something to her brain; it made her forget her English. She kept slipping into German, into the past.

I’d moved to Nashville by then but I would come back to visit her and in those last two weeks I went to stay with her. I brought my guitar; I sang her songs. That’s when she spoke to me about her lost family. When she was dying, I promised her that I would continue her search.

O’Donnell: Much of Inge’s silence was also due to shame, and what she felt had been her failings as a woman and a mother. Being German, and not having been singled out for persecution, also carried its own weight of guilt after the war. People became aware of the enormity of Nazism’s crimes.

My own identity as a half-German child, growing up in France, was shaped by it. I wondered how my family fit within that, though I had been told they didn’t support the Nazis. I thought of Germans as either good — which meant heroic — or bad. I never really thought of the people in the middle.

However much we would like to think that heroic resistance is within most people’s grasp, reality is much more nuanced. Erna’s and Inge’s stories are not ones of heroism and evil, but of survival. And that, in wartime, is what most people put first. Their stories really make one reflect, what would I have done, back then?

Black: I remember going to the Holocaust Museum as a kid with her and my grandad.

I’d always seen my Omi as this relaxed, open person. Suddenly, she was aloof. Of course, everyone that day was introspective. It’s a lot to take in. But it was more than that.

But I was 12, and at that age you can’t really get your head round all the implications of that terrible time. I was asking her lots of questions. I was curious. She was being very quiet.

My grandpa had to take me aside and say, “Look, Brinn, this to you is a museum, but these are times she lived through. We just need to kind of let her do her thing. And then maybe she’ll want to talk.”

I think it’s easy for us to say we would have taken a stand back then. But it wasn’t easy. And I don’t think people behave any differently now. Look at the abuse that’s allowed to go on in the sex trade. Or the fact that in this country, we have people in cages. Yet nobody really does anything about it.

O’Donnell: Both our grandmothers clearly had the gift of reinventing themselves, of moving on, and finding happiness despite the ruins of their former lives. In Inge’s case, war had led to more than the loss of her home. It broke her relationship with the love of her life. She fell in love with my grandfather Wolfgang when she was 17 and he 19. They thought their love could conquer the world. But she became a refugee, he was conscripted into the army and became a prisoner in a Soviet camp. Their love story didn’t survive that, but she still picked herself up again. She met someone else, built a family.

Erna lost her home and all her family. Whilst she lived with the anguish of not knowing what had happened to them, she still lived an extraordinary love story with your grandfather.

Black: They had an amazing love story. My grandad was from Deport, Texas. He grew up very poor. He lied about his age so he could go into service in the army. He never fought, but was part of the clean-up crew, and came to Germany in 1946.

He met Erna sometime in 1948 I think, when he went to Bremerhaven, where she was in a DP camp. They fell in love, even though he didn’t speak a lick of German. He had brought a German phrase book with him. I still have it. It’s full of her handwriting, where she had marked down words for them to communicate in.

They just had this connection. I think that after everything she went through, he was her safe place. She got an affidavit in 1952, so they could get married, two years after their first child, my aunt Carol, was born. He was posted all over the world and she went with him, before settling back in the U.S. They were great travelers. Theirs was a life of adventure.

O’Donnell: One of the most interesting things I learned in the course of writing my book was how much my grandmother’s story was part of my own identity. I became fascinated by her story when I was at a crossroads in my own life. I think one’s own troubles sometimes give us a greater capacity for introspection.

Right now, due to COVID-19, we are living through very strange times, and while we can’t compare this to the horrors of the war, I often think of her story, what she went through, what she overcame. I think of how it damaged her but also how, in spite of that damage, she gave herself permission to find happiness again.

Trauma has its own legacy. I now see her aloofness was a shield, a protection. By telling her story I want her to have a voice. I want to show people that survival is not easy, that emotional scars linger. But more than that, that it’s no barrier to eventually leading a happy life. Because her life, the one she built after these shattering events of the war, on the whole, was a happy one.

Black: Like you, I started this process when I was going through a time in my life where I needed to step away. I was going through a rubbish time, my dad was sick, and he had a lot of downtime. That’s when he told me he’d always wanted to discover his mom’s story. He said he knew so little about it because she never talks about it. So it started out as something we could do together but then it became something much bigger. The more I found out, the more lots of details from my childhood started to make sense, take on a different meaning. I remembered how when I was a kid and the internet came, Omi would always be on it. I realize now that she never gave up searching for her family.

I’m struck by how things seem to go in cycles. My family lived in Florida when I was a kid and in 1995 we lost everything in hurricane Andrew. We went to stay with my grandparents for two months. My mom was seven months’ pregnant and went into premature labor because of the stress. But my Omi couldn’t move, couldn’t bring herself to drive her to hospital. It must have been some kind of post-traumatic stress. She couldn’t handle having gone through losing everything, and watching it happen to her son.

O’Donnell: When I called my grandmother that first time I went to Kaliningrad, she said, “The circle is closing.” I didn’t understand it then, but I really feel that closing that circle not only helped me make sense of her story, but of who I am.

Black: I know what you mean. I have a favorite memory of Omi. I was in third grade, my parents were getting divorced, so I was staying with her. I was sitting on the bed with a towel wrapped round me. I’d just had a bath. She came to me and said, “Brinn Heather Feather” — that was her nickname for me — “I have something important to tell you. You need to know this and I want you never to forget it.”

“We all have a light within us.” And she said, “And when someone loves you, they ignite that light. Just like I love you. Nothing can ever take out that light. When somebody leaves, that light is still there.”

I think of that a lot now, knowing everything she went through.

O’Donnell: She spoke from her heart.

Black: Yes. And I see now, that it made me a more loving person, throughout my life. And will continue to do so.