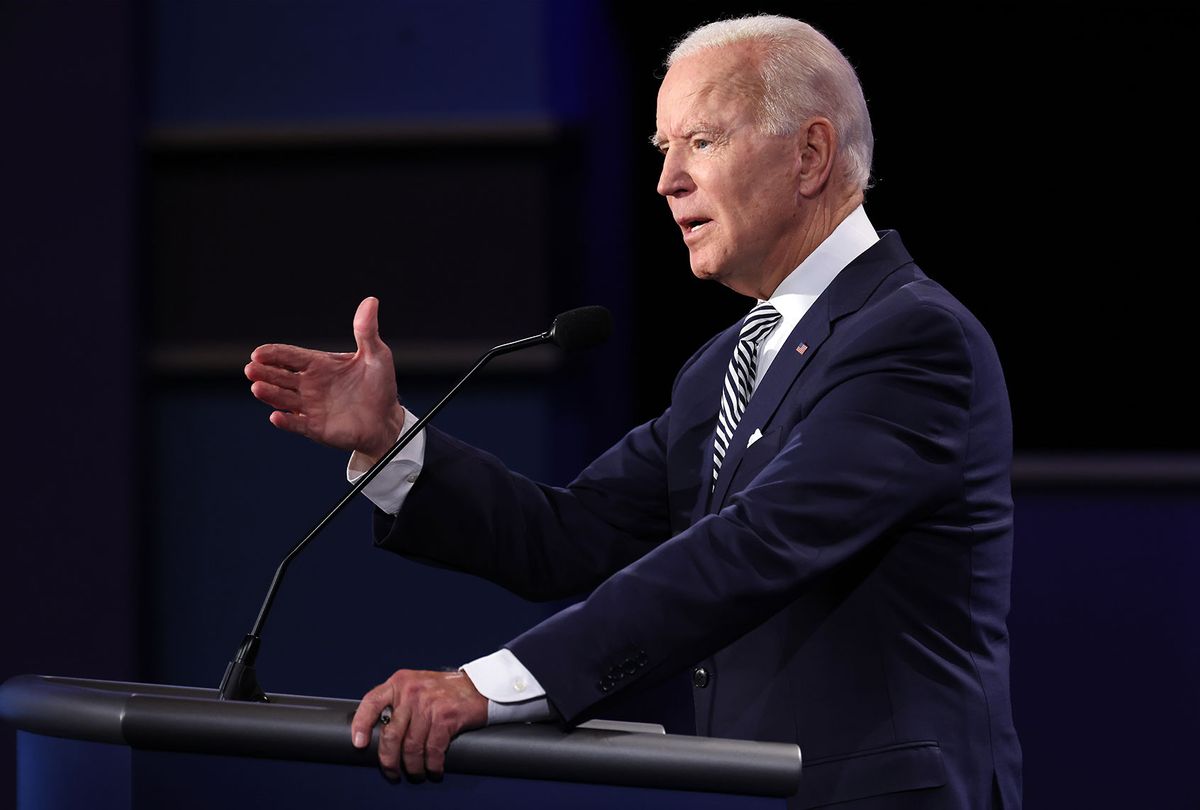

Last night during the presidential debate, I watched Joe Biden tell the world he was proud of his son conquering addiction. It might have meant nothing to most. But for the millions in recovery it was a breakthrough moment in the national conversation, a moment of admitting we exist. That addiction is a family disease.

"My son, like a lot of people you know at home, had a drug problem. He's overtaken it. He's fixed it. He's worked on it," Biden said. "And I'm proud of him. I'm proud of my son."

My dad never knew I got sober.

He passed away on May 23, 2011. At the time I was struggling. But if I'm honest, I had been absent for years leading up to that too.

On October 12, 2011, I attempted to take my own life. In a moment of clarity, I called my mother, who was, unbeknownst to me, celebrating one year of sobriety. Though we didn't have a good relationship, she talked me through it, and I haven't had a drink since. Now we joke that neither of us can back out of our sobriety or we won't share the same date anymore.

In a few days, she'll have 10 years.

My dad doesn't know any of that.

Throughout my years of sobriety and advocacy, a thread I've encountered over and over is shame. How shame keeps so many of us quiet; how shame kills so many of us. Addiction has been known for decades to be a disease, but let's be real: most Americans wonder why we can't just pull ourselves together. Even inside the recovery community, we don't always take advantage of all of the science available to us. Because even with years of sobriety under our belts, we fear what our friends and employers will say if they know. Aren't we just weak?

After I stopped drinking, so many people in my industry — theatre — came to me and said, "I'm so glad you got sober." Then they'd whisper something like, "I've been sober for three years." I was always thrilled to hear it, but I'd want to say, "where the F were you when I was struggling?" At the time I had felt so alone, like I was the only guy in the business who couldn't hold his liquor. But of course they were keeping their own issues quiet. They have careers and families, too.

Once you learn you're an alcoholic, the next word you learn is anonymous. We bake in shame from the beginning. We tell you, essentially, that we're so glad you're getting help, but be smart — you shouldn't tell anybody.

If I had cancer, people would run marathons for me. If I had diabetes, I could tell everyone and they'd share health tips. But I have a chemical reaction where my dopamine receptors take over my brain when alcohol enters my system, so instead I have to tell nobody and hope there's an open church basement near me in any town I visit. I don't get second medical opinions. I don't get the community to rally around me. I just quietly hope a system with no national organization or medical professionals is going to be there for me. And if I can go to rehab — if I can afford it or if my insurance covers it — regulation and licensing standards differ from state to state, and not all centers participate in national accreditation, so let's hope I picked a good one!

And why? Because it's a sickness where we think the people who get it should feel bad.

And then Joe Biden, a dad himself, went on national television and said his son had a problem and he was proud of him for conquering it.

It's not the same thing, but I'm reminded of the end of "Angels In America," where Tony Kushner writes of AIDS, "we won't die secret deaths anymore." What if we said that nationally, when it comes to addiction, we would accept no more secret deaths?

How many other sons and daughters will now consider telling their dads about their issues because they saw this? This isn't hyperbole: how many lives might be saved?

I didn't tell my dad when I was struggling and it almost cost me my life. I wish I had seen someone like Joe Biden on TV saying he was proud of his son.

I'm sitting next to my two-year-old daughter, another part of my life I wish Dad could know. She's watching "Sesame Street" so I can write. We know from science that she likely has a predisposition for addiction. If that happens, I want to be there for her, like Joe.

He's proud of his son. His son is alive. Pass it on. No more secret deaths.

Shares