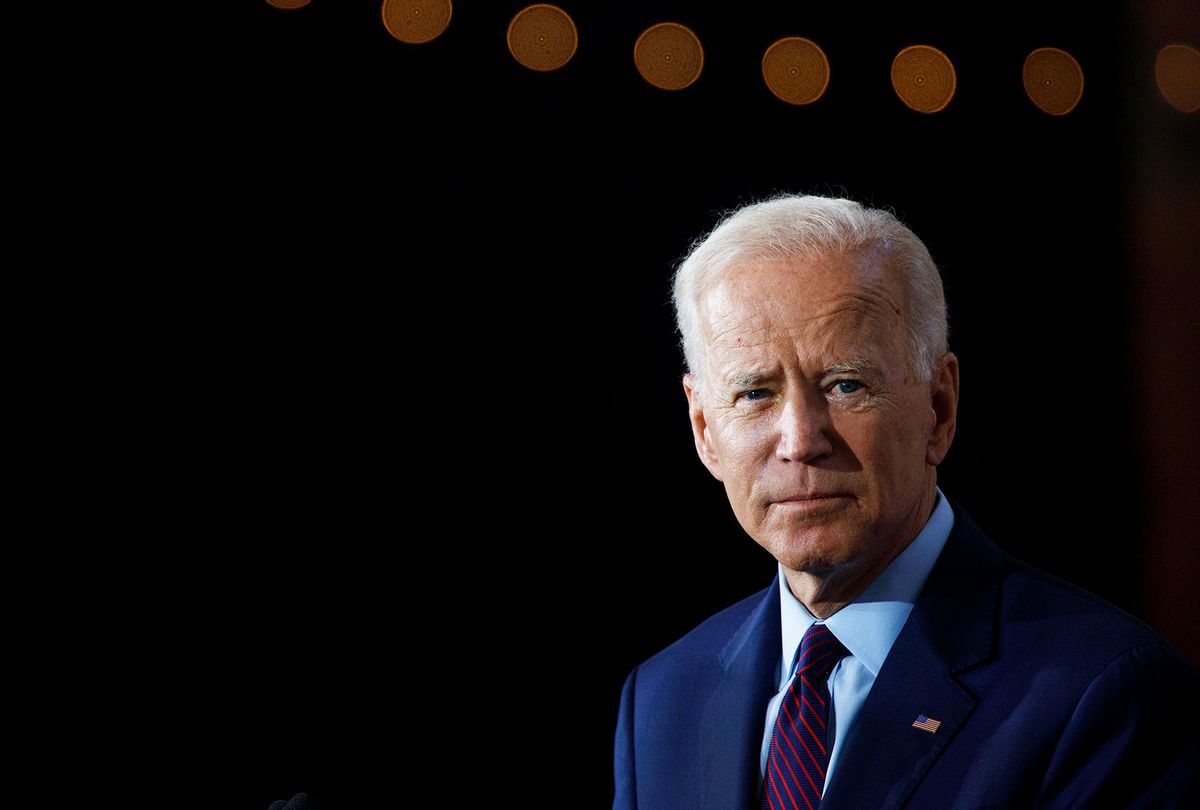

Ever since Joe Biden was declared president-elect, a new subgenre of stories has appeared about his forthcoming use of executive actions, in the New York Times, the Washington Post, NBC, CNN, NPR, The Hill, Mother Jones, Vox, etc. Some of these stories are standard issue — executive action is part of any new administration making its mark on the world, and prominent issues tend to draw special attention. But this year, the stories are more complicated, given the combination of Donald Trump's legacy, the sheer number of outstanding crises and the gridlocked, uncertain state of government.

Yet most, though not all, of these accounts tend to miss one crucial point: Biden has enormous power to shape a governing agenda, regardless of anything Congress might do — not just in one or two areas, but across the entirety of government. This point was first forcefully made 14 months ago, when the American Prospect rolled out what executive editor David Dayen dubbed "The Day One Agenda." This power does not reside primarily in the showy executive orders that Trump is so fond of signing, but rather in the matter-of-fact texts of laws passed by Congress over the long course of American history — specific grants of authority that are just sitting there, waiting to be exercised.

Not only is there tremendous agenda-setting power at the president's disposal, but a more recent Day One Agenda article, "Joe Biden's Four-Year Plan," underscored how such actions could help create a new governing coalition of engaged voters, much as Social Security and Medicare did in previous generations. Of all the articles published about executive action recently, Dylan Matthews' "10 enormously consequential things Biden can do without the Senate" in Vox stands out for grasping the breadth of possibilities, and explicitly drawing on the Day One Agenda. But it retains a typical Vox "here's some stuff" tone — it's absorbed in policy details, and divorced from the practical political considerations that have motivated the Day One Agenda all along.

Dayen told me in a recent interview that the idea started with "understanding the function of a president." He continued, "You go to Article II [of the Constitution], and you read what the job description of the president is, and other than being able to make treaties and being the commander in chief of the military, the main thing is that that they take care that the laws are faithfully executed. It's not that they have a legislative agenda or that they work to pass policy," he explained. "The idea is that Congress writes the laws and the president then implements the laws. Over the last 240-odd years, we've had a lot of laws written, and there's a rich tapestry within that set of laws that allows a president to put together an agenda that can make progress for people in really significant ways."

Not only is that what the Constitution clearly says, it's how things generally worked until the election of Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1932 — an issue we'll return to below. That's certainly not how the political establishment sees things today. In campaign debates, "The questions are all 'What are you going to do as president in terms of getting a legislative agenda passed?' and so seldom are the questions, 'What are you going to do to implement the laws that are already on the books?'" Dayen said. At the time, "Progressives were thinking in terms of a little bit of despair, because even if a progressive president were elected, Mitch McConnell would still either hold the Senate or have enough votes to frustrate any kind of a major bold policy shift," he said. "My whole goal was to counteract that and say, 'Look, here is an entire agenda, just sort of sitting there within the statutes waiting to be implemented.'"

What Dayen's publication found was a set of 30 meaningful executive actions with staggering potential, as he wrote at the time:

Without signing a single new law, the next president can lower prescription drug prices, cancel student debt, break up the big banks, give everybody who wants one a bank account, counteract the dominance of monopoly power, protect farmers from price discrimination and unfair dealing, force divestment from fossil fuel projects, close a slew of tax loopholes, hold crooked CEOs accountable, mandate reductions of greenhouse gas emissions, allow the effective legalization of marijuana, make it easier for 800,000 workers to join a union, and much, much more.

Along with his overview, the American Prospect published detailed articles on specific policies, which included feedback from the leading Democratic primary candidates. After the primary was over, the Prospect examined the Biden-Sanders unity task force document of policy recommendations and found 277 policies that Biden could implement without congressional action.

"On their own, none of these 277 policies will fully solve any of the interlinked crises we now face," wrote Max Moran. "But they can go a significant way toward immediate harm reduction. Some can even solve long-standing problems, simply by enforcing or fully implementing laws already on the books. Perhaps most important, all of these policies are ideas that leaders in the moderate and progressive wings of the party broadly agree on, and that Biden should have no excuse not to enact, save for his own policy preferences. There is no hiding behind Congress on these topics."

I asked Dayen about the relationship between the two lists, and he said the first represented "the most impactful ones," "the real high notes," that could be found in existing law, while the second culled everything that has been specifically agreed to. One important aspect here was to underscore the distinction between executive orders and executive action. Trump issued "a ton of executive orders" most of which "sounded good but they didn't really do anything," Dayen said. But he did wield real power through executive action, for example, giving farmers billions of dollars to compensate for losses from his ill-conceived trade war, when "he used a law from the New Deal called the Commodity Credit Corporation."

Trump's use of New Deal legislation is ironic on multiple levels. As noted before, Dayen's account of presidential and congressional power describes how things generally worked until the election of FDR in 1932, in the midst of the Great Recession — a cataclysmic catastrophe for which existing laws were clearly insufficient, and which Congress was clearly unable to deal with through its accustomed means. Roosevelt's famous "100 days" fundamentally altered how we saw presidential leadership — and extending well beyond the first 100 days. We came to expect presidents to initiate legislation, rather than simply sign or veto it. And the Constitution allowed for that to happen, simply because it wasn't forbidden.

Many conservatives objected to the New Deal, complained that it had resulted in a "Constitution in exile," but when they finally elected one of their own — Ronald Reagan — half a century later, they cheered him on for doing the exact same sort of thing. In truth, they just didn't like content of the New Deal, which tended to help out the wrong sorts of people, from their point of view. It was Trump, ironically enough, who has much more fundamentally upended Roosevelt's constitutional order. Aside from his tax-cut bill — some version of which any Republican president would have proposed — he hasn't passed any major legislation at all. He has been a model "constitutional," pre-New Deal president. Even his "destruction of the administrative state," to use Steve Bannon's phrase, is perfectly in line with what Reagan claimed to promise when he declared that government itself was the problem.

This does not suggest that conservatives were right and the New Deal was all a tragic, unconstitutional mistake. Quite the opposite: It was an absolutely necessary response to the crisis we faced at the time. We face a similar state of crisis today, although it has multiple different dimensions: the COVID pandemic, climate change, the racial justice struggle and worsening economic inequality, just to name a few. What we need is some way out of the polarization and gridlock we've drifted into over the course of the last several decades. The prospect of compromise-legislating our way out of this crisis is dim, to say the least. Just look at how long it's been since the last COVID relief bill was passed. We need to start where we are — with executive power that depends on nothing else.

This is the thread picked up in the aforementioned article, "Joe Biden's Four-Year Plan," by Jeff Spross. His argument there is simple: Trump is gone for now, "but the shadow of the 2024 election already looms," with a Trump-shaped Republican Party that "will eventually win power again," probably with a more competent authoritarian candidate. "The only way to avoid that fate is for Democrats to use this time to win domination over government for an extended period, forcing the GOP to fundamentally change its political course and character to maintain its own national viability," Spross argues, just as it was forced to moderate in the wake of the New Deal.

Dayen and Spross see things similarly. "My feeling on the election," Dayen told me, "is that enough people thought Donald Trump was ridiculous enough to throw him out of office, but they didn't necessarily trust Democrats to give them the keys to the car. The only way that you're going to earn that trust is by making progress with people. Now, that sounds kind of silly, because some people say, 'You can't really make progress unless you get the keys to the car, right?' But we've identified some ways we could make progress, in fact, and then build on that and build a coalition."

Spross speaks in generally similar terms. "You need to pass policies that have a very concrete effect on people's lives that they can notice quickly and that will have this effect for as broad a swath of the population as possible," he told me. "I talk about Social Security and Medicare as two premier examples of this. Social Security is literally a check you get from the government on a regular basis. You know it comes from the government. You know it's because the government wants to take care of you, to make sure you have a decent income in retirement. It's a significant sum of money, and makes a big difference. So it's transparent. It's a meaningful contribution to a person's well-being, and at this point it's something like 60 to 70 million recipients."

The political effect of that huge benefit is also huge, Spross observed, citing Andrea Campbell's book "How Policies Make Citizens," which showed "how Social Security changed the political engagement of seniors," who hadn't previously been a significant political force.

"The argument is basically, if you give people a benefit, a base level, they will be grateful for it," Spross said. "That will be a sign to them that government cares about them, that it's engaged with them, that it is concerned about their well-being. They in turn will be engaged with government: They will want to protect that benefit, they will want to expand it. And beyond that, the fact they have more income means more resources, which means more free time. That all equates to more opportunity to engage with politics."

So the trick is how to do something similar, using the tools at hand — in other words, with laws already on the books. Spross does consider the possibility of legislation passed through reconciliation — which would avoid the filibuster — should Democrats win the Georgia Senate runoffs and hold a bare majority. One example he cited in conversation was a universal child allowance, "something like Social Security for children," which could obviously have a tremendous impact. But he doesn't depend on passing new legislation. In the article, he argues that Biden must pick his spots: "Not just any executive action will do, however. The Biden White House would need to focus on those changes that, again, could deliver broad, meaningful, and recognizable benefits as quickly as possible."

As examples from the Day One Agenda, Spross cites canceling student debt, lowering prescription drug prices (two different laws allow for this), and initiating postal banking services (full-fledged universal services would require legislation, but targeted services and pilot projects wouldn't). He also cites removing marijuana from the schedule of controlled substances, helping hundreds of thousands of workers unionize, beefing up enforcement of worker safety laws, and possibly raising the federal poverty line, "which would automatically expand existing welfare benefits to many more American families."

There are lots of other things that need to be done — particularly when it comes to the climate crisis, an existential threat to all of us. They don't necessarily have the kind of quick constituency-building potential that Spross has focused on. That doesn't mean they should be ignored — that would be profoundly irresponsible. Rather, it means that those most concerned about those major issues should recognize that these constituency-building policies are pragmatically crucial to their work as well. The more one delves into the Day One Agenda, the more one comes to see political possibilities in a new light. That light, in turn, can help illuminate a way out of our current political deadlock, and all the crises that have stemmed from that.

Shares