Since the advent of at-home DNA testing and the proliferation of online genealogy websites where, with the click of a mouse, you could be connected with family members you didn’t even know you had, fertility fraud has increasingly served as a narrative device on scripted television.

Sometimes it’s as a punchline; there’s that third season turn in “Bored to Death” when it’s revealed that Jonathan Ames’ (Jason Schwartzman) potential girlfriend, Rose (Isla Fisher), is actually his half-sister. Their shared biological father was a man who ran a scammy fertility clinic where he just provided patients with his own sperm, despite telling them that it came from more “impressive” donors.

The concept also serves as the main throughline of “Sisters,” an Australian drama that opens on an elderly Nobel prize-winning scientist and fertility expert. He’s being cared for by his daughter, Julia (Maria Angelico). On his deathbed, he reveals that he substituted his own sperm in hundreds of IVF procedures, and Julia sets out to meet her new siblings.

The show wasn’t renewed for a second season, but an American adaptation, “Almost Family,” was released on Fox in October 2019. It was almost universally panned by critics for largely ignoring the issue of consent, instead veering into lighthearted dramedy about an unconventional family.

As TV Guide reported, the show’s creator, Annie Weisman stopped short of condemning the doctor’s actions when pressed by reporters at the Television Critics Association summer press tour, saying, “In any story, it’s important to feel empathy and understanding for every character . . . still contending with the consequences of his actions, but understanding that those types of innovators do cross lines in their singular quest.”

However, “Almost Family” never really reckoned with the real-life implications and trauma that the doctor’s actions would have rendered. After the show aired, “The Daily Beast” spoke with several individuals, like Julia Manes, who were born as a result of fertility fraud.

“I thought it was disgusting,” Manes told the publication “I think they minimized fertility fraud. It is medical rape and sexual assault. They made a comedy out of it. It was awful.”

While imperfect, HBO’s recent documentary, “Baby God” rights that wrong.

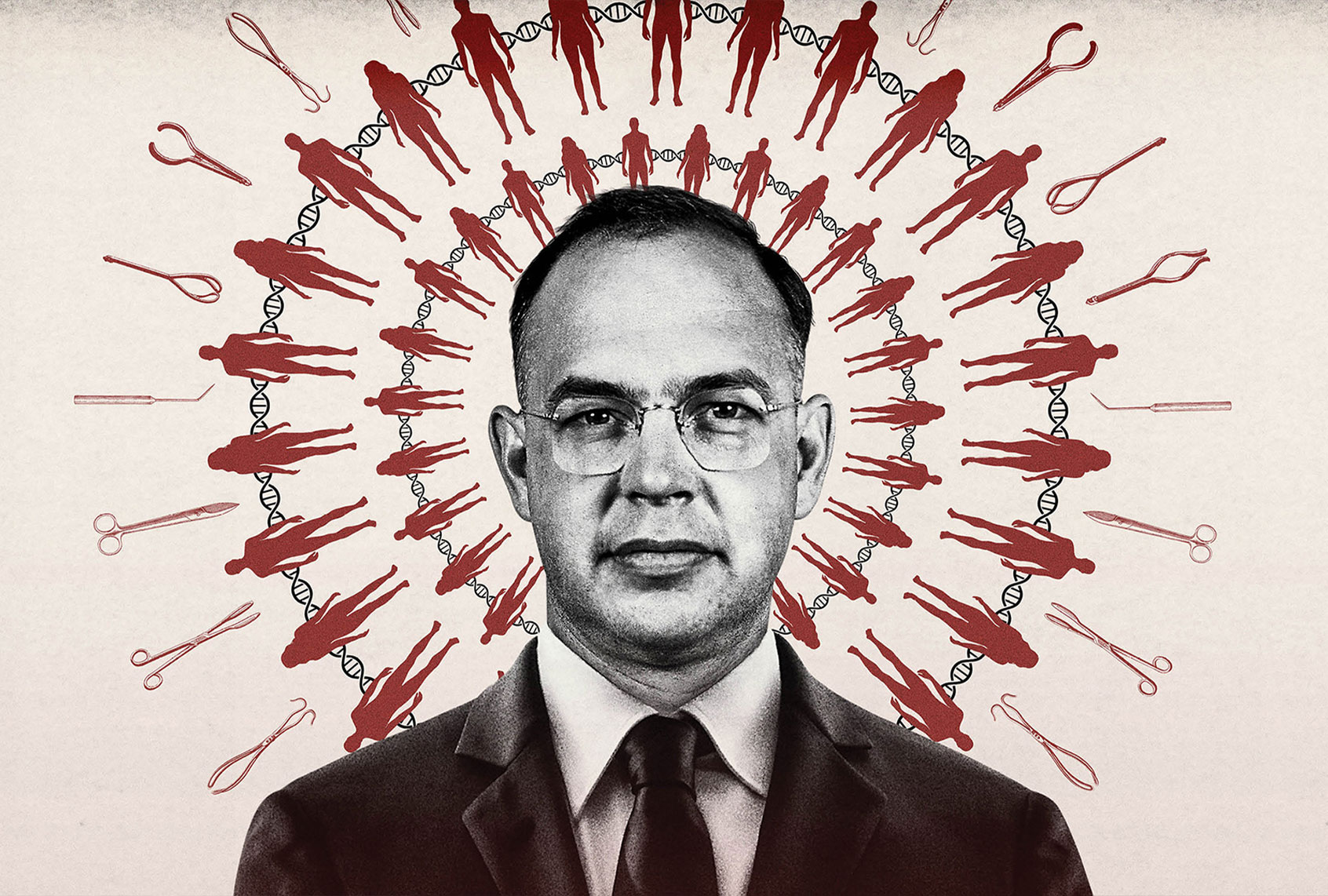

Over the course of 78 minutes, filmmaker Hannah Olson pieces together the crimes of Nevada obstetrician-gynecologist Dr. Quincy Fortier who worked into his 90s and secretly impregnated his fertility clinic patients with his own sperm. The exact number of patients isn’t known, nor the amount of children, though there’s evidence of children that he fathered being born from the 1940s to the 1980s.

Wendi Babst, one his daughters who is a retired detective and arguably the main character of this documentary, has found at least a dozen half-siblings. His son, Quincy Fortier Jr., speculates that “there had to be hundreds.”

The documentary primarily consists of interviews with the women who were secretly impregnated by Fortier, and with the children they conceived. Through Olson’s lens, these stories are stripped of any salaciousness (unlike “Almost Family” there are, thankfully, no siblings unwittingly having sex with each other plot points), but they never feel clinical.

Instead, she focuses on the human elements that connect them. Take Cathy Holm, Babst’s mother and one of Fortier’s patients who went to see him in the 1960s after she and her husband struggled to conceive. She was young, newly married and ready to become a mother. “I just really wanted to have a baby,” she murmurs to the camera.

As “Baby God” lays out, this was in the very early days of clinical artificial insemination; DNA wasn’t really understood and bodily and sexual autonomy were wonky terms that still largely just existed in textbooks and courts (Griswold v. Connecticut, the case in which the Court supported women’s rights to obtain birth control and thus, retain reproductive autonomy, without marital consent, was passed just before Babst’s birth). And, as Holms says, doctors were viewed like priests; they took an oath to do no harm, and people believed them.

Holms’ tone in the film is largely resigned.

It’s a tone that is mirrored by Dorothy Otis, a 94-year-old woman who consulted Fortier when she was a newlywed about a suspected infection. Unlike Holm, she didn’t want a baby — she wanted to go back to school — but was impregnated by him during what he claimed was a routine exam. “My life may have been altogether different,” she says.

“How can you go about changing the past?” both women seem to ask.

Many of Fortier’s children, however, are curious about how their father’s past impacts who they are today. The physical similarities are evident, especially in the case of Brad Gulko, who looks like a carbon copy of Fortier — but what about something deeper? Some of Fortier’s children ponder whether they get their coolness in social situations from him. Gulko, who is a geneticist, wonders whether he went into science because he inherited his father’s interest in the subject.

“Do you want to say your father was a monster?” Babst asks bluntly. “And what does that say about you?”

“Baby God” smartly doesn’t attempt to solve these questions by diving into the murky waters of nature versus nurture. However, Olson never really nails down Fortier’s motivation for his actions.

There’s a lot of speculation. Fortier Jr. says that his father justified his actions, saying, “I’m just helping out,” and a recording of Fortier’s own voice can be heard saying that it was common for doctors to mix their own sperm with the intended donor’s. Although Gulko addresses an animal’s primary biological motivation to breed diversely, he adds that “most people in a civilized society realize you can’t just do that.”

One of Fortier’s past patients raises the question, “Was he trying to see how many people he could have on this earth before he left?”

For much of the documentary, this seems like the likeliest explanation — that Fortier was a fertility expert with a god complex.

But then, as the documentary is beginning to wind down, it’s revealed that Fortier abused and molested his own children he had with his wife, crossing the line with one in a way that reflects on his clinic practices. “My father was crazy, he was a pervert,” Fortier Jr. says. “I think the happiest he ever made me was when he was laying in his coffin, dead.”

Using this revelation as a bombshell reveal, instead of as a starting point to characterize Fortier and his actions, is a narrative miscalculation. It would’ve stripped away any opportunity to justify Fortier’s fertility fraud, which one of his adopted daughters attempts to do, as a harmless means to an end that enabled women who wanted to be mothers become pregnant. Rather, it would have better framed Fortier’s story as that of an abuser who operated unchecked for his entire life.

In the end, however, it’s still clear that Fortier is a monster, and creates space to meditate on his children’s pain. “Baby God” treats its subjects with dignity and empathy and, unlike “Almost Family,” doesn’t shy away from the wreckage his legacy left behind.

“Baby God” is currently streaming on HBO Max.