Most pipelines that snake around the United States carry carbon that was buried underground for millions of years and then dug up, destined to be burned in a combustion engine or furnace or boiler and emitted into the atmosphere. But a new pipeline that could soon wind through Iowa, Minnesota, and the Dakotas promises to do the opposite.

Summit Carbon Solutions, a spinoff of an Iowa-based agricultural company, recently announced it is developing a $2 billion pipeline project that will carry carbon dioxide captured from ethanol refineries scattered across the Midwest to a site in North Dakota where it will be pumped thousands of feet underground. The CO2 will start in the atmosphere, where it is heating up the planet, and get sucked down to earth by stalks of corn. While some of it will be turned into ethanol and blended into gasoline, the rest will be returned to the earth's crust and — if all goes according to plan — buried forever.

If it gets built, the project will prove a new business model for carbon capture in the biofuels industry and expand the country's network of carbon dioxide pipelines, infrastructure that some researchers and climate advocates say is necessary to bring U.S. emissions down to zero.

Summit told Grist it already has agreements with enough biorefineries — a general term for facilities that create fuel out of organic material — to sequester 5 million tons of CO2 per year once all of the components of the project are up and running, which it expects to be in 2024. Its goal is to sign on additional partners, including other types of carbon-emitting facilities like fertilizer producers and power plants, to capture and store at least 10 million tons of CO2, which is about the amount that the state of Vermont emits in a year.

"With the inbound interest we've received from biorefineries and other industrial CO2 emitters since our project announcement, it's likely that we may even exceed" 10 million tons a year, said Bruce Rastetter, CEO of Summit Agricultural Group, in an email.

* * *

Carbon capture and storage, or CCS, is often criticized for being too expensive to be worthwhile, but the process looks fairly different depending on where the carbon is being captured. Fossil fuel–fired power plants emit a hodgepodge of gases, making it difficult and energy-intensive to build a capture system that can separate out the CO2. But at a biorefinery where corn or another form of biomass is fermented into ethanol, the process emits a pure stream of CO2, with just a little water vapor mixed in.

"There's no energy required for capture" at biorefineries, said Daniel Sanchez, an engineer and energy systems analyst at the University of California, Berkeley, explaining that only a small amount was needed to compress and dehydrate the gas. That's "the reason why this works so well, why it's cheap, and why everyone wants to do it," he said.

Still, very few do. Two biofuel plants in Kansas capture their CO2 and sell it to oil companies that pipe it out to aging oil fields and pump it underground to coax up additional oil — a process known as "enhanced oil recovery." Only one biorefinery buries its CO2 underground solely for the sake of taking it out of the atmosphere, and the project was enabled by substantial financial support from the Department of Energy. That plant, located in Decatur, Illinois, and owned by Archer Daniels Midland, has the capacity to capture 1 million tons of CO2 per year and bury it nearby. (As of 2019 the project was only capturing and storing about half that amount, which the company said was due to reduced ethanol production.)

Though it isn't hard to capture at a biorefinery, until recently, captured CO2 had little worth. But now the economic landscape is changing. Summit's project was made possible by a confluence of factors. First, in 2018, Congress increased the value of the 45Q tax credit, which will eventually pay up to $50 for every ton of carbon a facility captures and stores underground, and also made it easier to use. The final rules for the enhanced credit were released in January.

A second development came in 2019 when California's Air Resources Board adopted a new carbon capture and storage protocol for its low-carbon fuel standard. That means ethanol facilities that use CCS to lower the carbon intensity of their fuel can generate tradable credits when they sell it in California. Producers of dirtier fuels that don't meet California's standards have to buy those credits to comply. Recently, the credits have been selling for around $200 per ton of carbon. Summit told Grist it will earn revenue through the 45Q tax credit in addition to sharing the value of the California fuel standard credits with its partner biorefineries. The company also expects similar low-carbon fuel markets to develop in other parts of North America and around the world, potentially creating more demand for Summit's partner refineries.

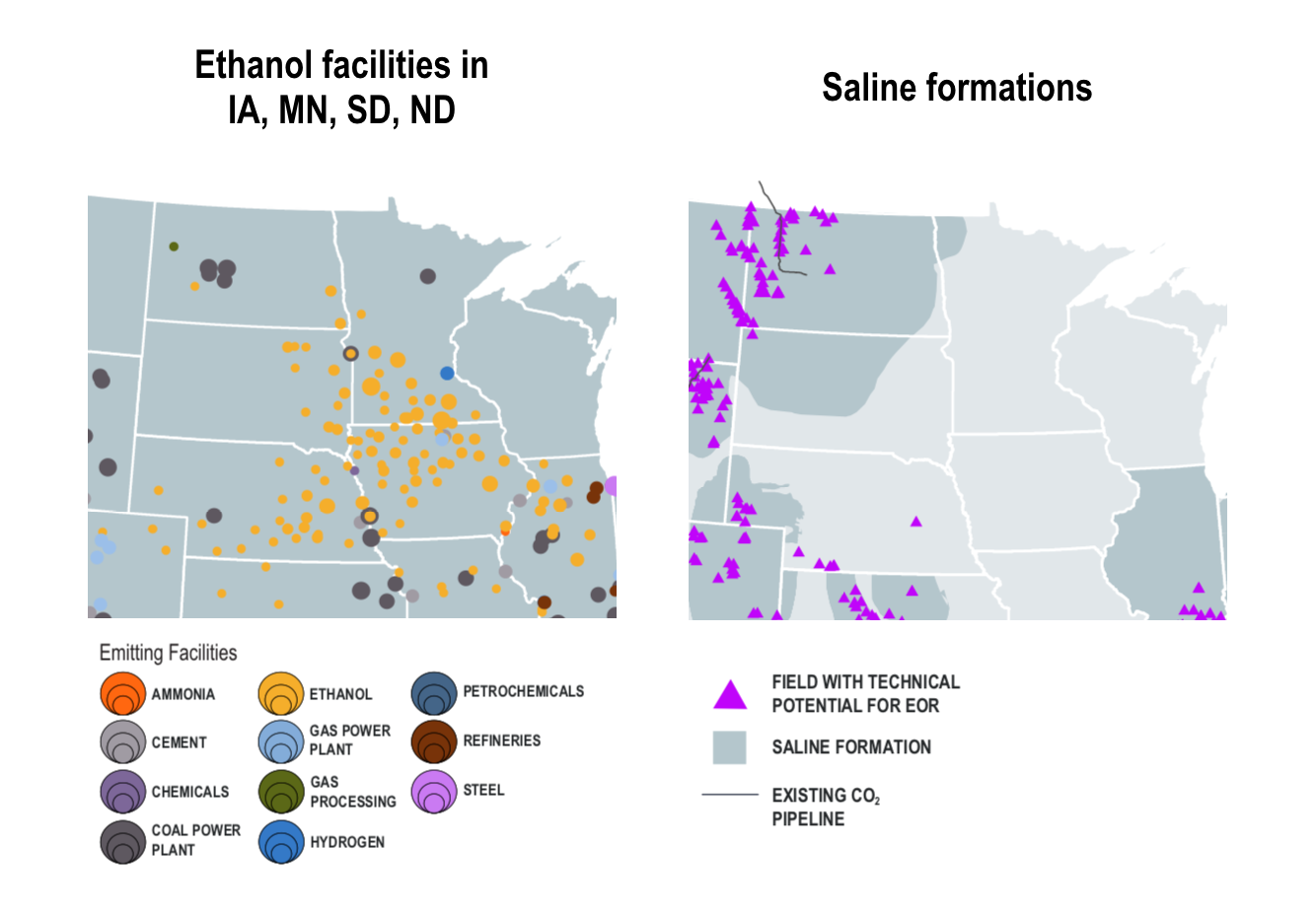

The third factor is that North Dakota is one of two states that the Environmental Protection Agency recently granted authority over regulating Class VI Underground Injection wells — the category of wells developed specifically for geologic sequestration of CO2 — making the permitting process much easier for companies that want to inject carbon underground. Unlike Iowa, Minnesota, or South Dakota, most of North Dakota sits atop the right geological conditions for CO2 storage, called deep saline formations.

Summit's project is designed to connect biorefineries dotting the midwest to saline formations in North Dakota.Dane McFarlane and Elizabeth Abramson / / Great Plains Institute

Brad Crabtree of the Great Plains Institute, an energy nonprofit that advocates for policies that support scaling up carbon capture and storage, said that the project not only benefits the climate but also creates a significant economic opportunity in the region. "I think it's groundbreaking in terms of its potential to transform perspectives and attitudes about what is possible in terms of addressing climate change and managing CO2," he said.

* * *

Growing crops for fuel has always been controversial, as it risks taking land away from food production, and cropland is sometimes created by razing forests and other important habitats. Growing corn, in particular, requires a lot of fertilizer, which can run off into nearby waters and create harmful algal blooms. But if you assess corn ethanol solely on the basis of greenhouse gas emissions, past studies have found that the average CO2 emissions from the full life cycle of producing and burning ethanol are about 20 percent lower than gasoline. A more recent study conducted by the U.S. Department of Agriculture asserts that ethanol production has become more efficient and currently emits, on average, 40 percent less CO2 than gasoline. (Ethanol doesn't fully replace gasoline — it is typically blended into gas at about 10 percent.)

Jeremy Martin, a senior scientist at the Union of Concerned Scientists, said that even as the world moves quickly to switch to electric vehicles, a full phase-out of gas-powered cars is going to take decades. It will take even longer to find zero-emissions solutions for airplanes and cargo ships, which are expected to increasingly adopt lower-carbon fuels made from biomass or hydrogen, in the meantime. "We're going to continue to use quite a bit of ethanol for quite a few years to come," he said. "We need to both do what we can to decarbonize all the fuels we're using and we need to move to the cleanest fuels that we can at the same time."

Sanchez said that adding CCS to the fermentation process, as Summit is doing, will probably reduce the carbon intensity of the ethanol by 30 to 40 percent. But there are other ways it can become cleaner still. Most biorefineries burn fossil fuels to create heat for the fermentation process, and capturing the emissions from that step or burning biomass instead of fossil fuels — or, better yet, both — would lower ethanol's carbon intensity further. Fertilizer plants produce a lot of emissions, and installing CCS technology there would also improve the life-cycle emissions for ethanol — since, remember, growing corn for ethanol requires fertilizer. In the long term, replacing corn with other crops that don't require as many resources to grow, like switchgrass, would also substantially improve ethanol's carbon footprint. Sanchez is optimistic that mechanisms like California's low-carbon fuel standard will continue to push the industry toward these cleaner options.

Beyond lowering the emissions associated with ethanol, Summit's pipeline project is a step toward building the infrastructure that some researchers and climate advocates say is necessary to bring U.S. emissions down to zero.

In a report released last year that looked at how the U.S. could achieve net-zero emissions by 2050, Princeton researchers found that success depends on a new national network of CO2 pipelines — potentially 70,000 miles worth. They found that even if the U.S. electrifies vehicles and buildings, and replaces almost all fossil fuel electricity with renewables, we'll likely need to capture CO2 from cement production (which can't yet be electrified), from gas-fired power plants (if any remain), from biofuels and hydrogen production, and maybe even from machines that can suck carbon directly out of the air — and transport it to a place where it can be used or sequestered underground.

The new secretary of energy, Jennifer Granholm, seems to agree. "Obviously, it's still nascent technology in capturing CO2 emissions, but we've got to do it on all types of fuel, if we're going to get to net-zero," she said in a recent interview with E&E News. "The CO2 pipelines that will be necessary for it could put lots of people to work, so I think it's a big job opportunity, I think it's a big carbon reduction opportunity, and we're going to be bullish about it."

Some climate advocates reject carbon capture on the basis that it extends a lifeline to carbon-intensive industries and technologies that should be phased out as quickly as possible. And carbon capture does not solve the air and water pollution issues associated with any of the industrial processes it has been proposed for. But when it comes to finding solutions for carbon emissions, Crabtree said that it's irresponsible to take options off the table.

He stressed that we are trying to decarbonize in a political context, where we need many stakeholders, including companies and workers, to support climate policy. He said carbon capture allows existing facilities that pay high-wage jobs to manage their emissions. "We have to be putting options on the table or we will not get to zero anywhere near in time," he said.

Shares