It was a dry day, like most days in the Judean Desert. It was the 1940s in the West Bank region of Qumran, where a group of Bedouin men were herding goats in the hills just west of the Dead Sea, so named because the water is so salty that very few organisms can survive in it. In the course of their day, the Bedouins noticed a nearby cave, in which they discovered clay jars filled with ancient leather scrolls. They had no idea they were about to forever change our understanding of Biblical history.

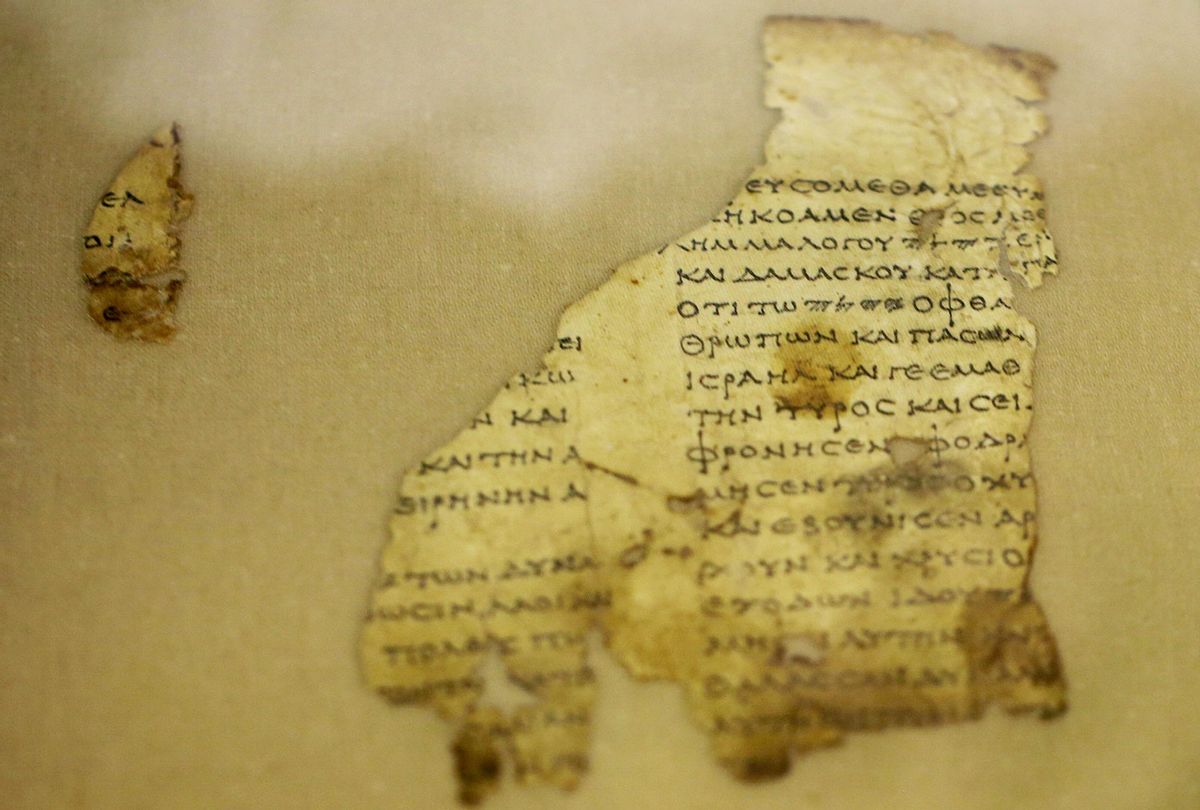

Over the following decade, fragments from more than 900 other scrolls were discovered in ten additional caves. Later dubbed the Dead Sea Scrolls, the documents contained passages from the Book of the Twelve Prophets, including the books of Zechariah and Nahum. These documents — versions of what Jews call the Tanakh, or what Christians would call the Old Testament — are mostly in Hebrew, although some were written in Aramaic, Greek and Nabataean-Aramaic. They are dated between the third century BCE and the first century CE.

And, as the world learned on Tuesday, new fragments from the scrolls were recently discovered.

According to the Israel Antiquities Authority, which owns many of the scrolls, a four-year archaeological project in the West Bank yielded the first new Dead Sea Scroll discoveries in 60 years. Besides fragments from the Book of the Twelve Prophets, archaeologists also found a 10,500 year old basket — quite possibly the oldest in the world — and the 6,000-year-old remains of a partially mummified child.

Learning how religious texts were written

The Dead Sea Scrolls have always fascinated archaeologists and historians for their capacity to rewrite history. The scrolls have shown how biblical texts are actually fungible: a few words re-ordered, and in some cases whole passages excised or rewritten, give insights into the history of these religious documents and help historians reconstruct how they were written and compiled.

"The new discoveries add a few more pieces to the puzzle that is the Dead Sea Scrolls," Oren Ableman, researcher at the Dead Sea Scrolls Unit of the Israel Antiquities Authority, told Salon by email. He mentioned that, among other things, they have helped scholars better reconstruct the text of the Greek Minor Prophets Scroll, which are Ancient Greek manuscripts of revised version of the Septuagint (or Greek Old Testament).

"The new fragments also included some textual changes in comparison to other manuscripts," Ableman added. "The most notable difference is that in Zechariah 8:16 instead of the word 'gates' — which appears in all other versions — one of the fragments has the word 'streets.'"

In the New King James Version of that Biblical passage, the text reads:

These are the things you shall do:

Speak each man the truth to his neighbor;

Give judgment in your gates for truth, justice, and peace.

Andrew Lawler, author of the upcoming book "Under Jerusalem: The Buried History of the World's Most Contested City" and contributing editor for Archaeology Magazine, told Salon that he was struck by how the fragments from the books of Zechariah and Nahum were written in Greek, even though most of the Dead Sea Scrolls are in Hebrew or Aramaic.

Lawler explained that the wording in the new fragments are very different from the wording of the same passages in the Greek Old Testament. That means that the sacred text "wasn't 'set in stone' for a long time," Lawler said. "The finds are a reminder of just how pervasive Hellenistic culture was in the Middle East even after the Romans came to dominate the region."

"What's also interesting is that the wording differs slightly from the Septuagint," Lawler wrote to Salon. After explaining what the Septuagint is, he added that "we don't yet know the age of the fragments, but they suggest the sacred text wasn't 'set in stone' for a long time.

What about the scrolls we've already found?

The Dead Sea Scrolls, both as previously discovered and with the new versions, fall into three categories. There are biblical manuscripts, which include versions of roughly 200 books from the Hebrew Bible. These are the oldest known copies of texts of those documents — which helped influence the three Abrahamic faiths (Judaism, Christianity and Islam) — in the history of the world. Fragments from all of the books from the Hebrew Bible were found there, except for the Book of Esther and the Book of Nehemiah.

There are also sectarian manuscripts, which include everything from apocalyptic proclamations and legal documents to commentary on the Bible. Finally there are the apocryphal manuscripts, which contain books that were not included in the Jewish Biblical canon and are either known only through translations or were previously undiscovered.

Taken together, they provide scholars with keen insights into how the foundational texts of many of the world's major religions were perceived in the Near East roughly two millennia ago.

"This is a huge subject since the entire field of textual study of the Hebrew Bible and the early Greek translations was changed by these discoveries," Ableman told Salon. "I think the best way to sum up the impact of the Dead Sea Scrolls in this regard is that they taught us that up to the early second century CE the text of the Bible was 'fluid.' A few different versions were in circulation at the time, although the differences between these versions was not too great and should not be exaggerated."

According to the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, there is one scroll that particularly stands out.

"The most outstanding of the Dead Sea Scrolls is undoubtedly the Isaiah Scroll (Manuscript A) – the only biblical scroll from Qumran that has been preserved in its entirety (it is 734 cm long)," the museum writes. "This scroll is also one of the oldest to have been preserved; scholars estimate that it was written around 100 BCE."

Why were the Dead Sea Scrolls hidden?

There is actually considerable scholarly debate over the origins of the Dead Sea Scrolls. One of the most popular theories is that they were stored in these caves by the Essenes, a separatist group in ancient Israel that was more religious than many of their contemporaries. They are known to have left for the wilderness to practice their faith, and may have been responsible for stashing the scrolls in those caves.

But this is not the only hypothesis behind their origins.

Indeed, some scholars believe that the documents were left behind by Jewish priests who "retreated to the desert," Lawler said. "Still others insist they were hidden by refugees fleeing the Roman siege of Jerusalem in 70 CE. It may be that the scrolls were secreted in the caves by a variety of people — both locals and refugees — during the tumultuous first and second centuries CE."

Lawler noted that the recent discovery may support the idea that the scrolls were put in these caves by a number of groups over varying periods of time.

"They were apparently placed in the cave during the second Jewish revolt that began around 132 CE, some half century after most of the other scrolls were hidden," Lawler told Salon. "Given that they also found a 10,000-year-old basket and a Roman sandal in this particular cave, there's no doubt that lots of people used these shelters for a variety of purposes."

Shares