Here's the biggest problem with Republican complaints that President Biden's American Jobs Act puts too little money — $621 billion — into ports, roads and bridges: Their so-called alternative would spend less than half as much on those urgent needs, only $236 billion.

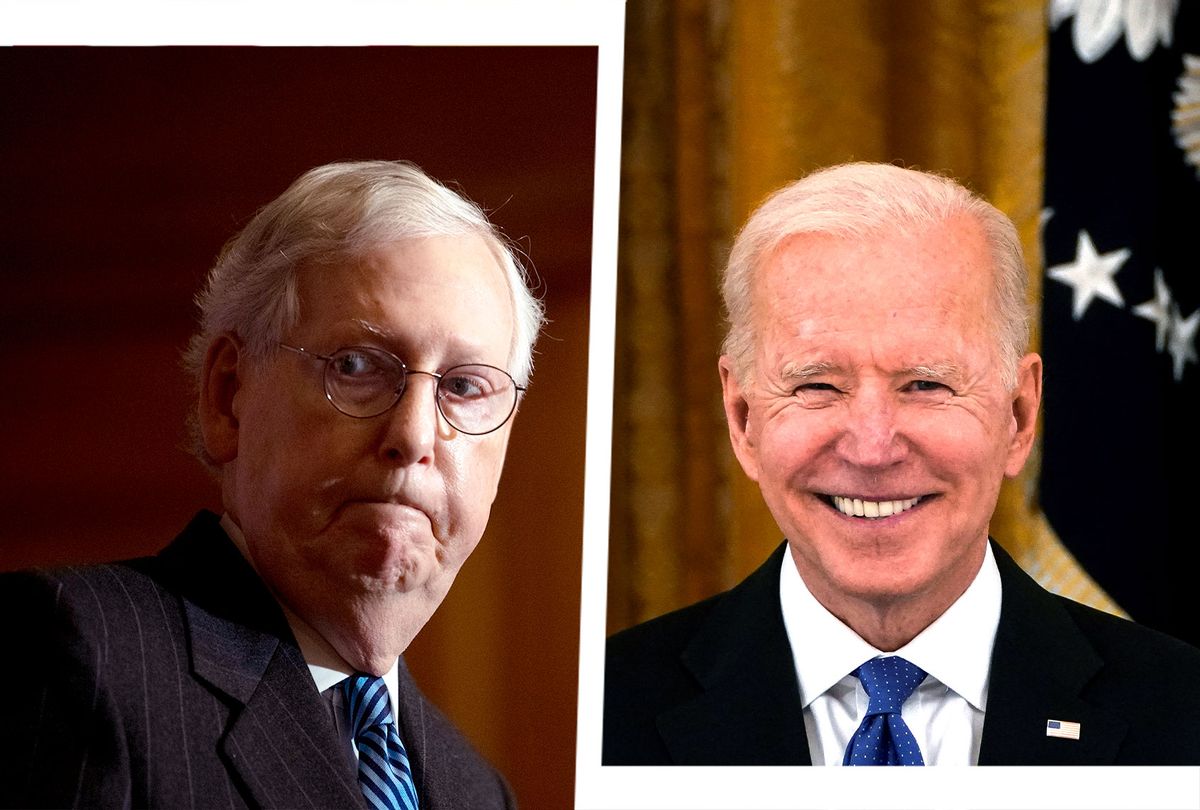

So when Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell is asked why he opposes the act, which would fund desperately needed enhancements to the bridge which crosses the Ohio River between Kentucky and Ohio, carrying 3% of America's GDP across it every year, he doesn't say his alternative would fix it — because it wouldn't. He simply grumps that he's not willing to raise taxes and increase the deficit to fix the bridge.

The maximum the Republicans will allow for all infrastructure projects is $600 billion — but the backlog of repairs alone of U.S. roads and bridges is $740 billion. Republicans are thus opposed, in principle, to investing the funds needed to give the U.S. world class infrastructure.

Austerity is the first principle the Republicans say they won't yield on. And here's the second: stagnation. Biden's proposal contains about $600 billion to accelerate U.S. leadership in 21st-century critical technologies like broadband internet, clean energy, a modernized national grid, electric vehicles and distributed manufacturing. These technology investments can be designed to pay for themselves out of the profits they generate, if Republicans prefer it that way. For example, the fuel cost savings of electrifying new postal delivery trucks would create a hefty surplus. (In just this fashion the Obama administration's investments in wind and solar energy and electric vehicles paid for themselves and made a profit.) So there is in fact no rational fiscal argument against profitable technology investments.

But Republicans object to the very idea of investing in U.S. technology leadership, because new technologies will displace the coal, oil and gas whose corporate producers and lobbyists currently fund the Republican Party. They are clinging to yesterday's economy. At one recent House hearing, Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers, R-Wash., argued that Chinese leadership in electric cars was somehow an argument against U.S. investment in EVs. Acting as if the electric vehicle future were optional, Rodgers questioned "the security impacts of the United States trading its strategic advantage in fossil energy for more reliance on supply chains from China."

This profound commitment to technology stagnation is the second pillar of Republican resistance to infrastructure investment. That neatly captures the American reality; a bipartisan infrastructure bill is blocked not by Biden or McConnell or Chuck Schumer's attitude about how the Senate should work, but by the fiercely defended Republican principles of spending as little as possible and changing as little as possible.

It's important to understand that during the last six years Republicans could have pushed an ambitious infrastructure bill through the Senate and House, attracting Democratic support and a White House signature, and financed it with user fees, a gasoline or perhaps a carbon tax and other business-friendly revenues. They could have crafted one big enough to meet the deferred maintenance gap on roads, bridges, ports, airports, water supplies, dams and sewers; and big enough to enable the U.S. to start catching up with China on high-tech innovations like advanced batteries and electric trucks. They didn't even offer one.

Now that we have a Democratic version to start with, we need to ask the opposition party the following questions:

- How do Republicans propose to finance the $500 billion gap between their proposed infrastructure compromise and the funds needed just to repair America's roads and bridges?

- What is the Republican plan to replace the thousands of miles of lead pipes and other unsafe drinking water infrastructure that is poisoning American families, also with an estimated backlog of over $500 billion? (These two items by themselves present a bare-bones need for $1 trillion.)

- Since we all appear to agree that broadband is important, what is their competing plan for catching the U.S. up with its "socialist" European competitors in terms of broadband access and speed? How would they pay for it?

- Finally, how do they propose to win the 21st-century innovation race with China and Europe for leadership in advanced technologies like wind, solar, telecommunications, distributed manufacturing and electrified transportation?

If they can't come up with reasonable answers that go beyond polite terms for austerity and stagnation, we should recognize that allowing the Republicans to block Biden's investment agenda means choosing a grim future for our country.

It means that in 2030 Americans will still drive dirty and expensive oil-powered cars and trucks on potholed roads across unreliable and congested bridges — vehicles other countries no longer allow to be imported and sold. American shippers will pay twice as much to get goods across the country as their Chinese competitors. Households will still endure unreliable and expensive utility bills, while wondering whether the drinking water in their taps is poisoning their children.

Even more of us will know a friend or neighbor who lost their job because the factory where they worked could no longer compete with China. American workers won't be able to compete with Europe for the digital jobs of 2040 because their broadband access won't be fast enough. This won't happen because of partisanship or the filibuster, although those are major barriers. It will happen because one of our two major parties is clinging to an impoverished view of what government should do for its people and to yesterday's fading fossil-fuel economy, which very soon will genuinely be unable to afford the investments America needs.

Shares