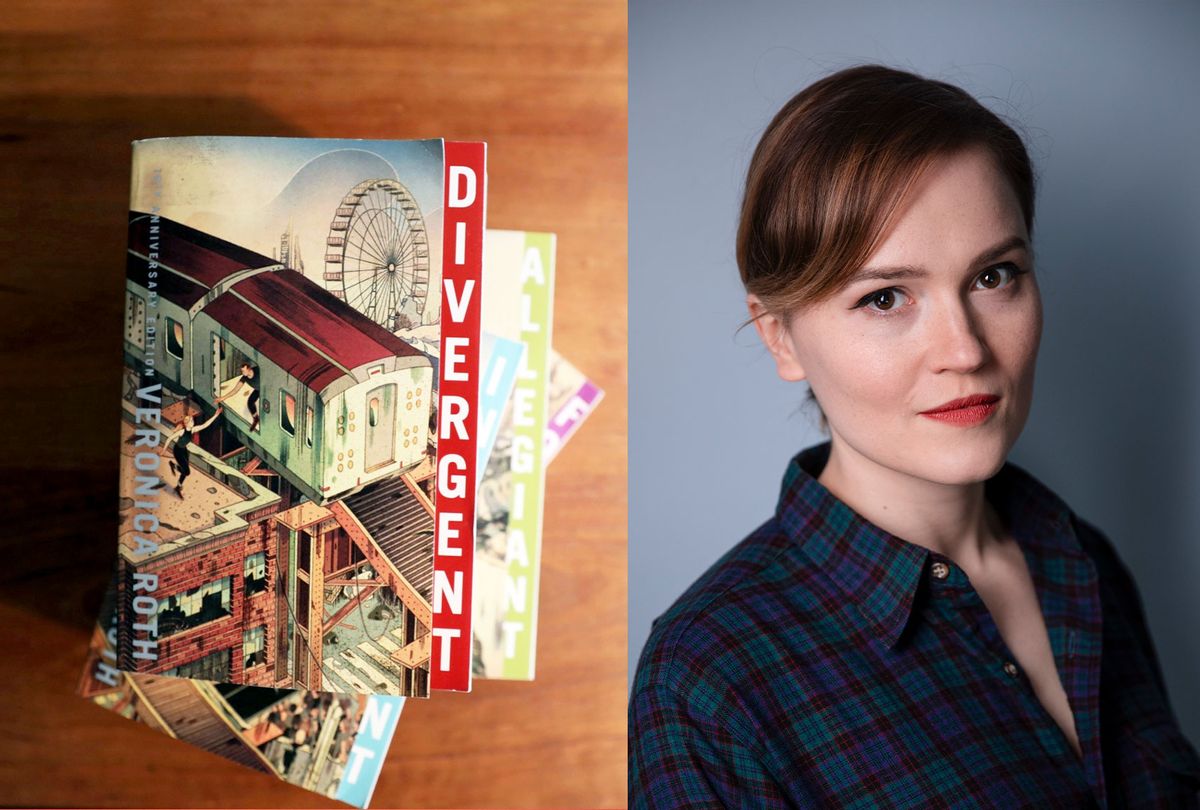

In November 2013, the third book in my bestselling "Divergent" series, "Allegiant," had been on the shelves for a few weeks, and I was on a run. It was cold, and I had lost my keys somewhere along my path. As I waited for my husband to drive back to the apartment to let me in, I sat on my back steps and tweeted about my misery, as one does. Within seconds, I received a reply: I hope you freeze to death. Without hesitating, I blocked the user and closed Twitter.

My reaction was automatic. At that point, I had been receiving angry messages — even threats — for weeks. Some were obvious hyperbole — like the person who threatened to "chop my breasts off" — and some were more frightening. It's harder to tell the difference than you'd think, and unlike many other women on the internet dealing with casual vitriol, I hadn't had much practice. Up until then, my mentions were pretty tame, nothing outside the norm for a new author. This intense anger was provoked by a particular decision I had made: to end my series with the death of my main character.

Since then, every single time I open myself to reader questions, I get this one: Do you regret it?

* * *

A good ending, my writing professor told me in college, is both surprising but inevitable — and you have to earn it. So when I reached the climax of my third book, I tried on different endings in my mind. I wanted to make sure that the one I had planned since the first book was really the right choice. They all felt wrong, like I was avoiding something. They felt like cowardice.

On the day I wrote that scene, I told my husband, "I'm just going to try it and see how it feels." I could always change it if it didn't feel right. My heart raced the entire time. When I finished that afternoon, I was emotional — not because I had written her death, but because I knew it would take. Everything inside me was steady; this felt like the right ending for Tris, the character who had been living in my head for three books. This was the one. I knew it the way I knew I wanted to be a writer, the way I knew "Divergent" was ready for submission, my inner compass pointing resolutely north.

And yet for months after I sent in the draft, I was nervous. Not because I thought it didn't work—I had set this ending up over the past two books, and to top it off, this installment, unlike the others, was written in two points of view. And not because I thought my readers would revolt — the death toll in the rest of the series was substantial, so surely they were prepared to lose characters at that point? But I worried I had been too obvious about it.

Hadn't I?

At the end of both "Divergent" and "Insurgent," Tris faced a kind of death — in one, she almost drowns; in the other, she's nearly executed. In those books, there was still more for her to become, more for her to understand about what sacrifice meant and why it was powerful, one of the fundamental questions of her character from the beginning. But at the end of "Allegiant," she was no longer becoming; she had become. And she gave her life for someone she loved despite his deep flaws. She saw what he needed, as her parents had once seen it for her. "Allegiant" therefore ended just as "Divergent" had, the books mirroring each other.

I was so sure everyone would see my handiwork and guess what was coming. It's almost funny to me now, how wrong I was.

* * *

At the time of "Allegiant"'s publication, the book set a record for number of preorders at its publishing house, HarperCollins — approaching half a million. It was wild, a rarity in YA before and since. That meant everyone would read the final installment at the same time. And as they finished, there was a collective burst of shock and grief over her death, with no one outside the readership to mitigate it. It created a storm in a teakettle. The reaction built momentum, and culminated in the threats and anger to which I later became desensitized.

The question I ask myself, ten years after "Divergent" first hit the shelves, is this: Is it the fault of my readers for not seeing my ending coming, or is it mine? Answering that question requires me to ask what my books conditioned them to expect. For me, raised on books like "Bridge to Terabithia," "A Summer to Die," "The Outsiders," "Harry Potter" — and later, "Flowers for Algernon," "For Whom the Bell Tolls" and "The Death of Ivan Ilyich" — losses are a part of reading. I expect them, and have never particularly minded. A painful loss in a book feels like practice for the greater losses that await us all in life, no matter who we are. Or they give the losses we have already endured a voice, a moment of recognition.

But none of that answers the question of whether I did a good enough job at setting up my ending. Does it feel surprising, but inevitable? Does it feel earned? Those aren't questions I can answer. The answers from others seem to be mixed, as they always are. But another thing I learned when studying writing is that the work must primarily speak for itself, and if people don't understand what you're up to, you shouldn't leap to blame them for it. My writing education taught me to strip away defensiveness and look at what's there, to be unafraid of what you'll find. So when I look back at the books, yes, I do wince in places, because it's my old work, and like any writer I can see now how many things I might have done better. I am sure that one day I will feel that way about the work I'm doing now, too.

But do I regret the way I ended my series? No. I don't, and I never have.

As time has gone on, the tone of the messages I receive from readers — people are still discovering the series anew after ten years! — has changed. There are more fans of the ending than there used to be, and that's nice for me, but I'm not talking about them. I'm talking about the ones who are sad — sometimes profoundly so — and plead with me to write another installment.

This plea feels like its own expression of grief. What do we feel after a loss but a desperate need to go back to the way things were before? That's impossible when we lose a loved one. But when we lose a beloved character, there is someone out there who can give us what we want, who could end our discomfort: the author. And the last few years have yielded results on that front in the form of continuations and reboots of stories — in books, movies and TV — we thought were long over.

But I'm not interested in providing an end to that discomfort. And it's not because I want to shock people, or because I am — as one morning show host once put it — "ruthless." It's because this ending is an exploration of resilience, for the characters that remain as well as for the reader. It communicates that losses can be endured. That healing is possible. That pain is not forever. That discomfort is OK. This is something I wish I could go back in time and say to the parents who scolded me in the signing line for making their teenagers cry: It's OK for your child to feel this. It's OK to care about something, and then lose it. It's OK that time doesn't run backward.

I cling to these messages myself as I contend with my own assortment of discomforts. As I watch my parents age, as I battle anxiety and chronic pain, as I experience the losses of this pandemic along with everyone else, as I come to terms with the fact that the wonderful anomaly with which I began my career is unlikely to occur again. As I age, and friendships fade, and my options, once endless, begin to narrow. The things I am enduring — the things we are all enduring — may not always be OK, but it is OK to feel sad about them. Sometimes life feels that way.

I did end up writing the closest thing I'll likely get to another installment: I explore the psychological aftermath of being a teenage "chosen one" in my most recent book (named, you guessed it, "Chosen Ones") and the cost of bearing heavy burdens at a young age. I even destroyed Chicago for a second time — my apologies to my fellow Chicagoans.

But as for "Allegiant" — nothing has changed. My inner compass is still pointing north.

Shares