Books about dogs are frequent, and also frequently romanticized, oversimplified, or dumbed down. You can count the ones that are great on one hand (I would mention, e.g., "Bandit," by Vicki Hearne, "My Dog Tulip," by J. R. Ackerley, and "The Dog of the Marriage," by Amy Hempel, or almost anything by Amy Hempel). "What Is a Dog?" by Chloe Shaw emerges startlingly from a field primarily of mediocrities, then, a remarkably perceptive memoir which is mostly about dogs — or, maybe, much more than that.

Maybe it's a memoir of Shaw's youth, and maybe it's not a memoir but rather a group portrait, one that is achingly attuned to the capacity of humans to fail to connect, and the connections instead that dogs can provide amid that failure: the lessons, the tutelage, the genuine and selfless love that dogs can give.

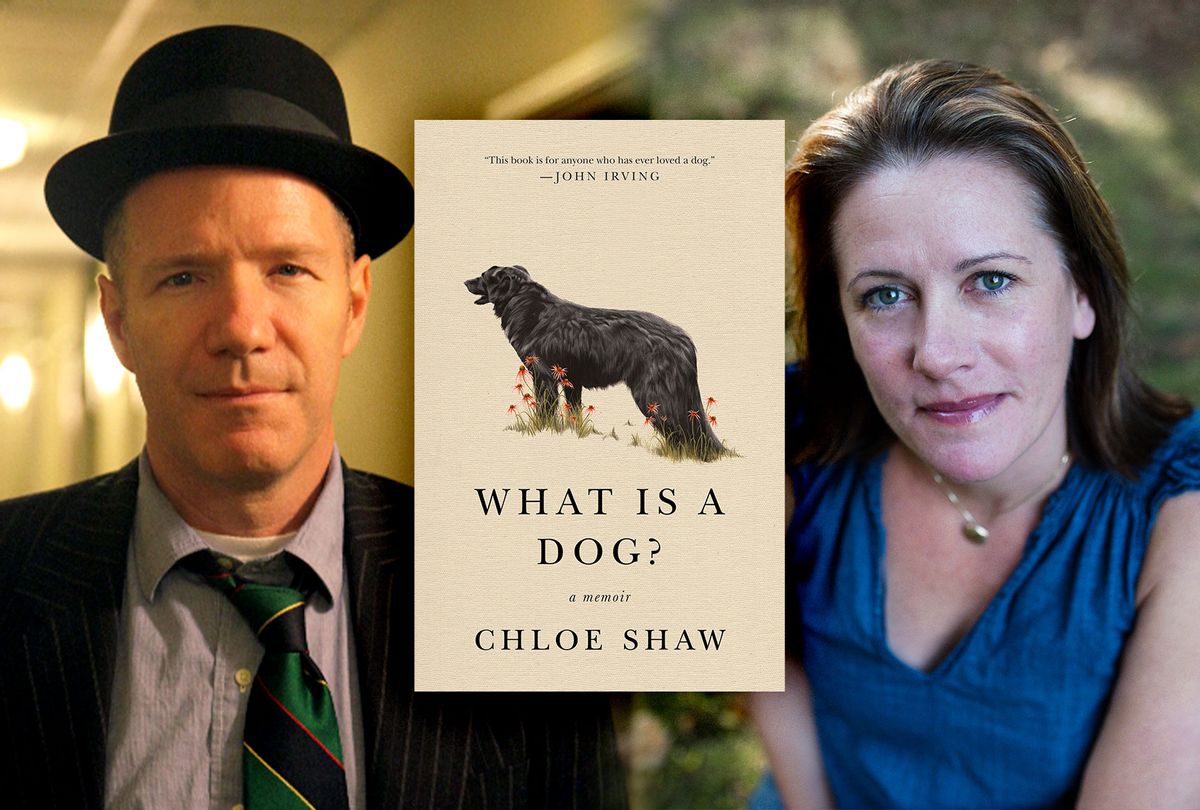

Chloe Shaw's voice, often lucid and funny, is, upon reflection, deeply observant and mournful, even as it celebrates what great companions her dogs have been. This is one of the most inventive memoirs of recent years, poignant and improbable as it nimbly sidesteps all the pitfalls of animal sentimentality. I was excited, therefore, to talk to the author (whom I have known for many years, it should be said), which we at last managed by email in June and July. Her interview voice is like her prose voice: charming, warm, and also very, very insightful.

Your title, "What Is a Dog?," is powerful and moving. How early in the process did you understand that this was the title, and that the title was essential to the book as a whole?

Thank you. This book began in essay form, which was published at The American Scholar. I finally sat down to write about our dear, departed dog, Booker, in one big burst a couple of years after he died. As I wrote from a place of specified grief, I began thinking not only about what he'd meant to me and represented in my life, but what all of the dogs that preceded him meant and represented. I began thinking more broadly and philosophically about what dogs are. What is a dog? I wrote early on in that essay, trying to conjure the first moment I ever saw one as an infant — my parent's afghan hound, Easy. (She was their first baby.) And that question took hold as I wrote, as I remembered, as I watched the world around me fill with dogs. I became more interested in the question of what a dogs is than why we love dogs. There's certainly an overlap here, but I felt like diving a bit deeper. And I had six willing subjects (four gone, two still here), with whom to do this deep dive. So the title seemed obvious the moment I typed the words. It's the question I asked myself over and over while writing both the essay and book. Without knowing it, I think I've always been asking this question and still ask it every day.

When I first knew you, back when, you were a fiction writer, more commonly, and I think, in those days, you were writing a lot of short-short stories. What occasioned to the transition over to nonfiction? Is it a permanent transition?

You have a good memory. We met and knew each other through 9/11. The shock of that experience settled in in myriad ways. One of them was that I found I couldn't sit still for long. My focus was shot. So I began writing short-shorts. They were the perfect format for me at that fractured time. The switch to nonfiction was not something I could have predicted. I finally sat down to write about Booker and my whole heart fell out. This was something I'd been struggling with in my fiction — not lack of heart, but vulnerability. Something about finally speaking from me as me allowed me a voice that felt relieving and powerful. I don't think I can say it's a permanent transition, but it has certainly muddied the waters as to what's next.

There are ways that "What Is a Dog?" advances a very important literary agenda: It muddies the debate about what constitutes a complex character. Booker's characterization, for example, amounts to "personhood," especially in the truly powerful monologue he gives in the first chapter. There are not that many great literary works that have attempted to describe animal point of view accurately. ("Flush," by Virginia Woolf, might be an example.) Did you think about the book this way, as an investigation of what constitutes a literary character? Or was it simply a by-product of trying to describe the dogs of your life?

Oh, "Flush." It's been so long since I read it, but what a magnificent book! I can't say I had this idea of literary character in mind, so I suppose it was mostly a by-product. But I am an unabashed, life-long anthropomorphizer. I can't help it. So perhaps what you are noting is a by-product of that tendency as well. I certainly took my job as dog translator seriously. The monologue of which you speak is something I swear I heard come straight out of Booker's black-spotted-tongued mouth.

I'm a little bit interested in the opposite idea in your book (the opposite of anthropomorphism, that is), in which it appears that humans have some dog-like characteristics. Or, to put it another way, is the title asking us if the categories of human and dog are really stable? Maybe there is enormous shared terrain? After all, I think you, the Chloe-narrator, begin the book lying on a dog bed, yes?

I love this question. I do not think the categories are stable. After all, I have spent much of my life being the dog in lieu of Me. And, of course, as you point out, I've found myself quite literally on many a dog bed over the years. I do believe there is enormous shared terrain. Something mutually animal seemed to be exchanged back when the first wolves (who some believe happened to be nicer wolves on the great scale of wolf etiquette) befriended us. They needed our food and we needed their loyalty and ever-ready, fluff-filled affection. All these years and generations later, now they need our loyalty and affection, too. I think we've landed together in an exact middle ground of our two species. My relationship with my dogs feels a bit like a romance. It's a commitment that requires patience, humility and a good listening ear. I know dogs don't talk the way we do, but they surely speak to us if we listen.

A slightly heretical question. What about your cats? They have only a small role here, but will they get a volume of their own? Or is feline consciousness too different?

I have often joked that my next project will be "What Is A Cat?" Though I'm not sure I feel fully qualified. Feline consciousness is so different, yes. But living with both has a kind of balancing effect. While my dogs mostly cater to my human self-absorption, my cats have been self-absorbed beings of their own. In other words, they've kept me in check. Unfortunately, I've lost both Tito and Lolita these last two years. It definitely threw off the balance in this Peaceable Kingdom. I miss the challenge of keeping not two, but three species content under one roof. That's always been such a beastly thrill for me, having successful inter-species relationships. I mean, what an honor! I'm not saying I haven't been looking at kittens on Petfinder, but (in case my husband is reading this) I'm also not saying I have ....

Can you talk about the humans/dogs/creativity balance in your life? How do work the writing in, and is animal care a help with this question in any way?

I was lucky enough to receive my MFA as a younger person amidst multi-aged people. I had three slightly older friends and inspirations — Dinah, Sue, and Sally — who were all not only also getting their MFAs, but raising families. (I didn't even have a dog or cat back then.) I remember feeling in awe of them, of all they were doing, all at once. Their examples certainly taught me how to use any minutes I have available. I wrote two novels during baby naps, in the spaces between feedings, and before anyone woke up. I am so lucky to have a supportive extended family, including very involved grandparents on both sides and lovely friends who show up. But the balance was also between my husband and me. As a psychoanalyst, he has a full, consistent case load, and as a writer, I'm supposedly more flexible. A blank page awaits, not a human. But I've come to see that blank page as my version of that human, and so has he. We've learned to share household/parenting responsibilities because that blank page and human both matter deeply. In terms of animal methodology, all three things feel animal to me, innate: writing, time among dogs, and becoming a mother. I do feel like they all intertwine. All three, lifeblood. I must do a little of each in order to get out of bed every day. I'm not sure it ever feels quite balanced — but working, rotating forward.

One last question. The book, as I make my way through it, seems to have a shadow subject, which I belief is, as you have noted about Booker, the subject of grief. I hope that does not seem like a spoiler, or like I am controlling interpretations in some fashion. But in a way this memoir is a catalogue of loving relationships with dogs in which the fact that dogs have (mostly) shorter life spans than their humans becomes an unassailable truth. This coming to terms with grief, then, seems central to the work as I read it. Does that feel accurate? Do you feel you have any special accumulated wisdom with respect to this inevitability of loss?

Grief is, I would say, the second subject of the book (next to dogs), but as my friend Larry reminded me after his wife died, that means it's also largely about love. I knew that Booker broke me open to grief in the singular experience of his death, but now that you mention that catalogue of loving relationships with dogs, I realize that it's better stated this way: it was a more gradual process over many years that culminated with the loss of him, which was the turning point for me. I believe one of the best lessons of empathy in childhood comes from animals. Whether you're able to have a pet, visit a local shelter or farm, animals don't speak the way we do so we must listen harder and listen differently, and therefore give up something of ourselves. I'm not sure it could be called special wisdom, but what I learned through my dogs is how to show up in times of big emotion. How not to turn away. How to talk to my kids about sorrow and loss and all of the love that goes with those experiences, too, and to try my best to normalize emotions, big and small. Dogs certainly let you know how they're feeling without shame. My hope is the same for humans. For this human, dogs have helped.

Chloe Shaw lives in Connecticut with her husband, two kids, and two dogs. "What is a Dog?" is her literary debut.

Shares