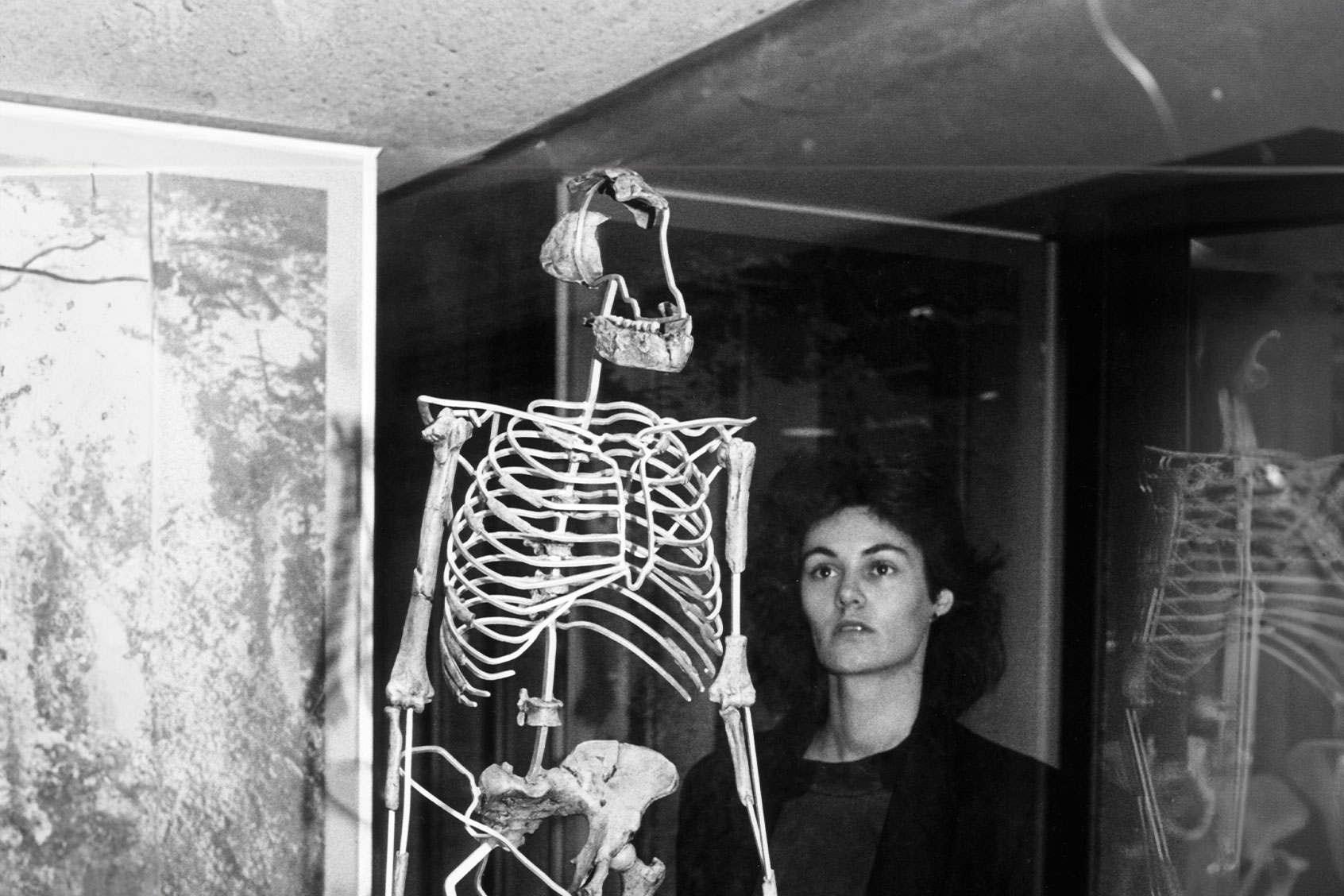

Poet and scientist Cat Bohannon wants you to try this thought experiment: Picture an alternate opening of Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 classic movie “2001: A Space Odyssey.” The original begins with the iconic (and much parodied) scene in which a band of ape-like early humans beats a rival tribe into submission. After their victory, one of them triumphantly tosses his bludgeon, a masculine, violent tool, which morphs into a spaceship. But in the new version, the scene opens on a pregnant female waddling off to give birth with the assistance of another, older female. After the birth, this proto-midwife raises the newborn overhead, triumphant, and the scene melts into one of a woman holding a baby on a spaceship.

Humanity managed to survive and conquer the world, Bohannon argues in “Eve: How the Female Body Drove 200 Million Years of Human Evolution," not because of bludgeons but because of something else: gynecology. Giving birth as a human is incredibly dangerous, and in Bohannon’s view, practices that helped us survive that process, such as reproductive choice and midwifery, should be venerated as drivers of civilization.

What if instead of telling the same old stories about how male achievement shaped humanity, we rewrote our evolutionary and social history through the lens of the female body? This is the ambitious premise shaping this doorstopper of a book that reframes the history of the human body and of human culture, from deep time until the present.

Bohannon’s sweeping narrative examines the evolution of breastfeeding, the womb and menopause, as well as the female body’s contributions to features shared by all genders, such as perception, our musculoskeletal system and the brain. What emerges is a sort of feminist, science-minded version of David Graeber and David Wengrow’s 2021 bestseller "The Dawn of Everything."

The bias toward male bodies in the stories we tell about humanity has social and cultural implications, of course, but it also has implications for health and medicine.

The book is lively, comprehensive, sometimes provocative, and always thought-provoking. Bohannon, who holds a Ph.D. from Columbia University in the evolution of narrative and cognition, has been working on this project for a long time. She sold the proposal to her publisher more than 10 years ago, after another pop culture experience — an installment in the “Alien” movie franchise — got her thinking about how we need a “user’s manual for the female mammal.”

The bias toward male bodies in the stories we tell about humanity has social and cultural implications, of course, but it also has implications for health and medicine. From 1996 to 2006, 79 percent of the animal studies published in the journal Pain examined only males, a paradigm partly fueled by the fact that the male body is considered a less complicated subject without the variable of the female reproductive cycle.

But as Bohannon tells us, “When scientists study only the male norm, we’re getting less than half of a complicated picture,” which has dire implications for women. For example, we only started testing for sex differences in general anesthesia in 1999, despite the fact that the female body often responds to the drug differently than males. (Bohannon is careful to acknowledge the existence of nonbinary and trans identities, reminding us that “Trans women are women. Full stop.” But she uses the terms “female,” “women,” “male” and “men” as shorthand for “bodies that are assigned female or male at birth,” a stylistic choice adopted in this review).

What if instead of telling the same old stories about how male achievement shaped humanity, we rewrote our evolutionary and social history through the lens of the female body?

Bohannon structures her book in relative order of when the traits that make us human, and made humanity possible, developed. In each chapter, we encounter what she calls an Eve, the earliest known creature that exhibited a certain trait, from live birth to bipedalism, from perception to menopause.

Our first Eve is Morgie, a mouse-weasel that lived in the Jurassic era and first fed newborns with milk — a revolutionary practice and one of the first steps towards the creation of humanity, since a mother’s milk, through its immunization properties, “extends the protective borders of her body to envelop her children.”

In subsequent chapters, Bohannon examines how each evolving trait later influenced the rise of humanity and continues to play a role today. She argues, for example, that the feeding practice pioneered by Morgie led to the adoption of wet nurses in ancient cities like Babylon and Thebes, which allowed for the population explosion necessary for humanity to conquer the globe.

Many of the later chapters are devoted not to female-specific features such as wombs and milk, but rather to female versions of body parts shared by all humans. In these chapters, we meet modern-day characters such as Captain Griest, a soldier attempting to become the first woman to complete the notoriously treacherous Army Ranger School test, whose story Bohannon uses to probe the question of whether men are stronger than women (she concludes that the genders have different strengths).

We also meet Abedo, an Afghan woman who fought in the Soviet-Afghan war and survived long enough to impart essential knowledge to the next generation of fighters; Bohannon uses her story to examine why women live past menopause, hypothesizing that it behooves humanity to have older women around to pass knowledge down through the years.

Bohannon asks us to imagine a world where we appreciate and celebrate these differences rather than casting value judgments.

Bohannon also draws on her own experiences. She recalls, for instance, her stint as an art model in college, when the male students drew her breasts bigger than the female students did, which caused her to wonder if she was literally living in a different perceptual reality than men. She also recalls her time as a broke 20-something, when she nearly became a sex worker, which caused her to ponder the oft-repeated story that the history of womankind is intrinsically tied to the history of prostitution.

Her general conclusion: The female body isn’t any better or worse than the male body. In some ways, all bodies are quite similar, no matter the gender: Until puberty, there’s very little difference between an XX brain, an XY brain, and a trans brain, Bohannon writes. It is true that, during puberty, female test scores tend to drop, which some take as evidence of the female brain’s inferiority. But Bohannon chalks up that drop in scores to a sexist society that forces girls into the patriarchy’s control after menarche. Constant surveillance, fear, and stress take their toll on a developing brain.

In other ways, though, the human body does vary biologically from gender to gender. The female brain literally changes when its owner is pregnant, for example, and while women are not as good at feats of speed and strength as men are, there is evidence that suggests they may be better at endurance — for example, although men outperform women in marathons and shorter races, women often run faster than men in the longest ultramarathons. According to Bohannon, this may be because women have more so-called slow-twitch muscle fibers than men, whose bodies favor fast-twitch muscles. The former is better for endurance and the latter better for strength and speed.

Women also may have a marginally better sense of smell and are less likely to be red-green color-blind than men, Bohannon writes — intriguingly, 12 percent of girls are something called tetrachromats, which means that due to an additional type of retinal cone, they have the potential to see the world in four color dimensions rather than the normal three. Bohannon asks us to imagine a world where we appreciate and celebrate these differences rather than casting value judgments.

Some of her conclusions are sure to rankle social conservatives, such as her description of the Bruce effect, a mechanism by which many animals’ bodies spontaneously abort unwanted babies, and her related exhortation to consider human abortion natural.

Other theories and ideas, and the hard questions she asks, might also prove challenging for feminists. (Bohannon is clear that she also identifies as a feminist.) Although she states repeatedly that she doesn’t want to rely on the shopworn story of motherhood as the ultimate expression of the female experience, some passages flirt with this trope. She imagines, for example, a mother inventing storytelling by soothing her child with a tale, a speculative scene that hewed too closely to tired narratives for my comfort.

One of the hard questions she tackles head-on is whether humanity evolved to be sexist for a reason. She argues that sexism evolved in early hominid societies in order to control reproduction and minimize dangerous births. She claims we also evolved the patriarchy for a reason, when our female ancestors made a so-called “devil’s bargain” by collaborating with protective men, who could offer food and shelter in exchange for sex.

Many women will not be happy to read such conclusions. But as Bohannon reminds us, just because we don’t like something doesn’t mean it’s false. And, crucially, she also reminds us that the evolution of our biology is only part of the story. There’s also the evolution of our culture, which we change through the traits Bohannon identifies as the most human: problem-solving, collaboration, and storytelling. Just because our ancestors — our Eves, as Bohannon would have it — chose to make that devil’s bargain doesn’t mean that we have to keep choosing it if it no longer serves us.

One of the hard questions Bohannon tackles head-on is whether humanity evolved to be sexist for a reason.

Ultimately, Bohannon’s book is a joy to read: It’s replete with beautiful language (“Her belly fat and swollen and hanging low, like an old fig”) and humor (“Our Eves rejoiced then — or however much a half-starved, apocalyptic weasel-rat can rejoice.”) It’s also an informative, intriguing, sometimes frustrating call to view our human story through the evolution of women and the essential contributions that the female body has made toward the genesis of humanity.

As Bohannon writes: “The ideas that human beings have about reality — what it’s made of, how it works, how we all fit into grander schemata — can change fundamentally.”

With this book, she’s calling for us to make that fundamental change. What would our world look like if we changed our reality to shake off our tired stories about male triumphalism and female subordination? If we venerated the strengths of the female body the same way we venerate the male? If we centered women as the norm and honored their contributions to our evolutionary history as they deserve to be honored? Bohannon thinks it’s high time we found out.

Emily Cataneo is a writer and journalist from New England whose work has appeared in Slate, NPR, the Baffler, and Atlas Obscura, among other publications.

This article was originally published on Undark. Read the original article.