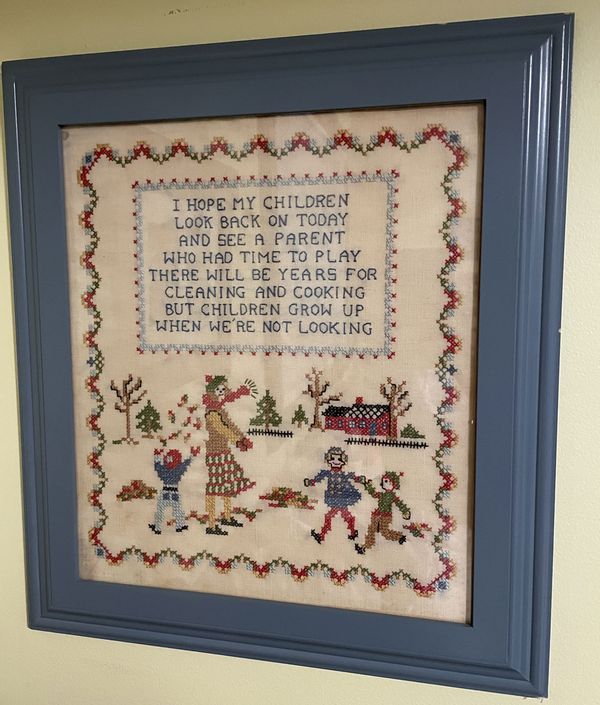

There is an embroidered saying that has hung on the wall in my parents’ house for as long as I can remember, declaring “There will be years for cleaning and cooking / But children grow up when we’re not looking.”

The sentiment made me uneasy as a child and also uneasy as a parent, particularly during the year I turned 38, and the phrase haunted me so thoroughly that the sing-song fear crept into my writing. In a scene where the narrator considers how often she finds herself seeking reprieve from the constant look-heres of parenting, she is racked with guilt over how she can be both aware of the future — when her children will leave — and yet unable to “savor every single moment.”

I am deflecting by referring to her as “the narrator.”

I am also deflecting by not including the entire phrase:

“I hope my children look back on today and see a parent who had time to play.

There will be years for cleaning and cooking, but children grow up when we’re not looking.”

Embroidery poster (Photo courtesy of author)

Embroidery poster (Photo courtesy of author)

The truth is that even in my self-condemnations, I couldn’t admit the crumple in my soul that the “hope” suggested because I was afraid there was no way my children would ever remember me as a parent who had prioritized play.

This is the terrible dichotomy of parenting: it exhausts while you are in it; you have the energy for it when it is over.

The parent is confessing that they are not always looking. Yet the mother in the embroidery is not deflecting — she is fully present with her children. The mother is not looking at her children but at the embroiderer, at the camera lens. Her scarf is high in the wind, she wears mittens on her hands, the leaves are red and gold and green. Her home is far away; she has left her responsibilities and come out here into the front yard, past the faraway fence, to be with her children. Her lips crook up ever so slightly, unlike the obvious smile on the blue-coated girl — the girl I always knew was me, the oldest child. The mother is allowing her son — my brother, facing away from the embroidered — to throw leaves at her, like the photo my parents took when I was 16, my brother 14, my sister 12. We had driven out West and found snow at high altitude in July; there is a photo of the three of us throwing snowballs at my mom, the photographer.

My parents have hung the embroidered saying in the bedroom they reserve for my daughters — a bedroom that serves no function other than for my children to sleep in when we visit my parents, who live six hours away from us. My parents have outfitted the room with a bunk bed and an additional twin bed, loaded the bookshelves, stuffed the closet with toys my daughters have played with over the years. I am always touched by how much my parents care for my children. There is something my parents know that I do not, which is how it feels when this time has passed. I am trying to inoculate myself against it, steeling my heart because I am terrified of the destruction if I do not. My children will leave me — I have known this since before they were born. I never intended to train them to stay. But the hush I seek now will become the hush I cannot fill when they are no longer coming and going, no longer asking me to play. I will not sweep the broom every day, will not stack their breakfast dishes with a sigh, will not wipe their Nutella smears off the countertop.

This is the terrible dichotomy of parenting: it exhausts while you are in it; you have the energy for it when it is over.

I have loved my daughters at every stage of their growth. I was not one of those baby-moms who missed the baby stage when it left; I looked forward to the next, to the toddle, to the reading, to the school days. I am a rabid fan of my children’s activities, hollering at every single soccer game, in the basketball stands clapping so hard I get bruises on my palms. Framed on the wall beside my desk, the card one of my daughters drew for me, commemorating their performance of “Sisters” from "White Christmas" for my 40th birthday gift.

Yet: I missed my middle daughter’s starring role in her middle school play because I was at a conference.

The fear of what happens when we’re not looking. How even as a child that phrase filled me with a melancholy, knowing I would grow away from being a child, would assume the position of my mother, would no longer be my parents’ child. The tremendous ache of aging, the inevitability toward the change my parents always applauded — I grew another two inches since last year! — but also toward the truth that growing meant I would have to leave them one day. I would leave my parents, as we both always expected, and they might miss the moment when I did. They might miss me. The horror that my parents might NOT miss me.

A hard part of that embroidered saying is the use of “we’re,” because it means the embroiderer is aware that loss is a generational knowledge; the saying commemorates a generational desire to be different than we actually are, acknowledges the necessity of making the art to remind ourselves of who we cannot be. Who we know we are supposed to be.

I think about my parents often when I examine my conscience and ask myself if I am being the mother I can be.

There WILL be years for cleaning and cooking, but when you are raising children, you do not always have time to play. Cleaning and cooking is part of being a parent, part of caretaking, part of how I — as someone with Acts of Service as one of my top Love Languages — show love. My second Love Language is Quality Time. I am trying to do both.

But the hardest part of the saying is the hope because it means the embroiderer is aware that it is a pipe dream and wants to shape her children’s memories otherwise. I think about my parents often when I examine my conscience and ask myself if I am being the mother I can be. In my memories, I frequently consign my father to the garage because I remember him there so often, but I pair every trip to the garage with my father on the carpet beside me and my siblings, explaining the rules of wrestling and then gleefully declaring THERE ARE NO RULES! before we squeal and scramble to topple him together. I remember my father standing in the cul-de-sac hitting Domes with his tennis racket for me to catch in my softball mitt.

I remember my mother at all my events — the recorder concerts, the middle school basketball games I largely spent on the bench, the Spell Bowl Championships — and I remember my mother driving me to the mall, the movies, the friends’ houses. I remember my mother taking me to the library and the store for the posterboards I forgot I needed the night before the projects were due.

I remember my mother cleaning and cooking, but I struggle to remember her playing with me. I was so young before my playmates (my siblings) were born and my mother did not need to play with me so much anymore. It is something I struggle with now as my own children age and I list for them the litany of activities to which I once took them — the endless library storytimes that only lasted 20 minutes, the interminable afternoons at the children’s museum, the Mudpies at Fontenelle Forest as my children toddled from finger-painting to craft to snack to book and I dutifully followed them around the room, bored out of my mind — and they recall none of it. All those years I invested in making my children feel loved and none of the memories have stayed with them.

I suppose that is why the embroidery exists. I suppose that is where the hope comes from. I love my mother tremendously and when I think of all the meals she made for us—and cleaned up after! and did our laundry and vacuumed the carpets and made sure our lunches were made!—I know my mother’s Love Language must be Acts of Service as well. Perhaps it becomes a mother’s love language.

I think of Jill Talbot in her memoir "The Way We Weren’t," asked what she would like to do differently when she leaves rehab and telling her counselor, “I want to play in the leaves with Indie.”

I think of Ramona’s mother in her titular book (Beverly Cleary’s "Ramona and Her Mother") confessing to her daughters that she was tired of “being sensible all the time,” telling Ramona and Beezus she wanted to “sit on a cushion in the sunshine…and blow the fluff off dandelions.” Beezus replies, “But you always said we shouldn’t blow on dandelions because we would scatter seeds” and her mother sighs, says, “I know, very sensible of me,” gets up and goes to her chores.

All those years I invested in making my children feel loved and none of the memories have stayed with them.

When I Google the embroidered phrase on my parents’ wall, I can only find misquotes, all changing the “parent” to “mother,” which I suppose I should have expected. One website considers my embroidery to be a bastardization of the poem “Song for a Fifth Child” by Ruth Hulburt Hamilton, published in 1958, the year my mother was born. Ruth’s poem directly addresses mothers, not parents, and refers to the messiness of the house because the mother is upstairs with her youngest (and last) child, rocking her baby because she knows this phase will pass quickly.

When I was a young mother — and I was a young mother, my first daughter born when I was 25 years old — I knew I intended to have more. I was happy with each stage of my daughters’ growth because it made things easier; watching my daughters develop their independent skills was a stage I actively and loudly celebrated. Even my youngest, because by the time she was born, I was exhausted. The morning she emerged I was euphoric: the whole family I had desired to create was now present, there was no one left to hope for.

My daughters are curious about my writing; of course they are. Like the embroidery on the wall in my parents’ house, the sight of me at my desk, typing and staring at a screen, has been a fixture in my daughters’ childhood home. I haven’t wanted them to read about these years of my life until they have lived them for themselves. I don’t want my experience to color theirs; don’t want them referencing my missteps or judging me until they emerge on the other side and become parents themselves, a future which no one may desire and which also may not be assured.

I finally called my mother to ask her about the embroidery and she told me she had sewed it herself. My mother embroidered the cross-stitch sometime when she was pregnant with my younger sister. I asked my mother what it meant to her, the phrase, and she told me she embraced the philosophy and spent time with her children rather than keeping a clean house. Yet I remember a clean house AND a present mother, though not one who played with her children. This is the wisdom I can only hope is a generational inheritance I will someday accept: a mother does not need her children to remember their shared history the same way she does. She trusts her memories. Embroidering the truth is framing her love around her intention, which was always looking.

Shares