“There is nothing this world finds more terrifying than a woman with a microphone.” – Stacey Lynn Brown

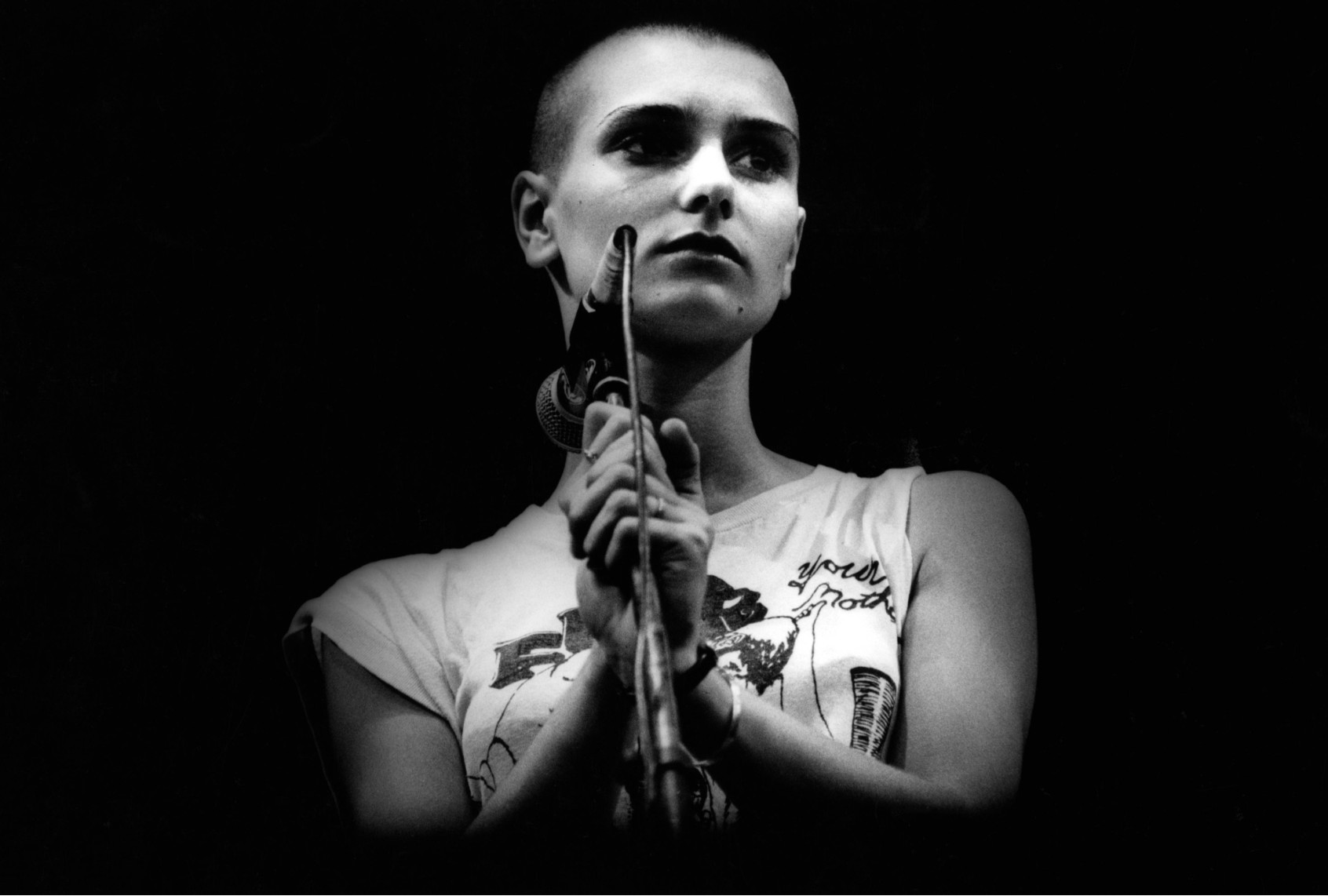

When Sinéad O’Connor left the planet in July of 2023 at the age of 56, the internet coalesced into a digital wake, with feeds full of tributes, song quotes and memories. For every person posting about “Nothing Compares 2 U,” there were those who could immediately reference the songs she made that were not chart-topping, million-selling, MTV-at-the-top-of-every-hour hits — memories of “War” or “I Am Stretched On Your Grave” or her cover of “Don’t Cry For Me, Argentina.”

“It felt really wonderful in the midst of people being so sad about losing her that a conversation could unite us, in the dream of a project that might help us deal with our grief, but also kind of seek to understand what we were experiencing.”

Writer Sonya Huber witnessed all of this taking place, and the reaction made her think: “I wanted this song (‘The Last Day of Our Acquaintance‘), and I needed other writers to choose theirs.” Huber made a post on Facebook to this effect, and when she looked at it hours later, the many responses made her realize that she had opened a channel. She wrote, “. . .it turned out that hundreds of people, too, had the song, the one song of many songs, each the essence of a flame we were lucky to have been lit by that told us the truth that no one else would.”

Together with co-editor Martha Bayne, these two writers corralled the groundswell of grief, tribute, loss and love into a call for proposals, and the result is a new anthology, “Nothing Compares to You: What Sinéad O’Connor Means to Us.” The book features 26 essays by women and non-binary contributors, each piece of writing focusing on one song from across O’Connor’s 10-album (and more) discography.

“It felt really wonderful in the midst of people being so sad about losing her that a conversation could unite us, in the dream of a project that might help us deal with our grief, but also kind of seek to understand what we were experiencing,” Huber told Salon. “I think many of us had sort of put Sinéad on the back burner, you know? And so to sort of re-appreciate exactly or re-understand in the first place what she meant to us was, it was a really welcome sort of truing up. And I’m a person with a thousand and one hairbrained ideas, so I was just like, ‘OK, we’ll see how this goes, we’ll see what happens.’ But the fact that we’re now [here] today with this thing published is quite a shock.”

The essays, arranged in an order corresponding to O’Connor’s discography, are individually formidable, well-written, heartfelt and heart-rending; the essayists picking their song and then connecting that song to “some kind of pivotal experience in your life, whether a moment of challenge or transformation or joy,” co-editor Martha Bayne explained. The essays are in first person, and that is the one overarching similarity; they are personal, all digging deep in a way that surely required an admirable degree of courage.

Start your day with essential news from Salon.

Sign up for our free morning newsletter, Crash Course.

(To that end, there is a caution on a page just after the table of contents, stating: “The essays collected here address difficult and often painful subjects, including child abuse, sexual assault, racialized violence and suicide.” It’s not accidental that those also happen to be subjects that Sinéad O’Connor wrote, discussed and sang about.)

But this book is absolutely not trauma porn; it is, instead, a celebration of life, both of Sinéad herself as well as each of the authors of the essays. The anthology is filled with story after story of survival that was manifested, accompanied by, or assisted by the sound of O’Connor’s voice echoing in the writer’s ears, head, heart, or pit of the stomach. They are beautiful, and you will cheer every single writer on. The voices are unique, diverse and international, which is important because the vilification O’Connor experienced in the United States after her historic “Saturday Night Live” performance (where she ripped up a picture of the Pope) did not destroy her career overseas the way it did in America.

This book is absolutely not trauma porn; it is, instead, a celebration of life, both of Sinéad herself as well as each of the authors of the essays.

The other element that elevates this particular book is each writer’s individual understanding and comprehension of Sinéad O’Connor’s music. The fandom, appreciation, or admiration expressed is as vivid as the memories, understanding, or the pain expressed. Essay after essay also recognizes how O’Connor was demonized and made into a pariah because the last thing society wanted was for her to inspire other women to disobey, or at least not to conform, or be willing to push back.

Megan Stielstra touches on this in her essay about “Nothing Compares 2 U,” the most popular song pitched to the co-editors. Within this stunningly simple piece that artfully weaves together her modern-day reaction to Sinéad’s passing to her father’s terminal illness to her picking up the pieces of her own life, she talks about how the song was nominated for three Grammys and that O’Connor refused to appear on the program, instead issuing an open letter to the music industry outlining her objections. Stielstra remembers, “It was the first time I remember a woman saying no, it made me ask why she said no, and the search for that why showed me that a song is so much more than a song, that music and language are tools.” You will understand why this essay was the chosen one in a crowded field.

Writer Zoe Zolbrod takes us into a punk rock group house in Philadelphia where the women sit around the kitchen listening to Sinéad’s music, and how one by one, many of the women also shaved their hair off, in tribute or alignment. (Shaving one’s head after discovering O’Connor’s music is a very shared experience, appearing more than once throughout the book.) Writing about the song “Jackie,” the first song from O’Connor’s 1987 debut “The Lion and the Cobra,” she observes, “We didn’t have to be told that Sinéad shaved off her hair in response to her record label’s plan to market her as a pretty girl.” And in her essay on “Mandinka,” Irish writer Sinéad Gleeson talks about how she hated her name as a child and how fundamental the other Sinéad’s appearance was: “We had been waiting for her for a long time,” she explains, reminding us of the repressive and patriarchal society both Sinéads emerged from.

We need your help to stay independent

Other repeated themes: how Sinéad O’Connor was right, mostly about the Catholic church, but many other things as well. Gina Frangello discusses O’Connor’s “lineage of resistance” not just for musicians, but for social activists. Frangello writes, “I long to reach into the past and beg, ‘Don’t throw yourself on the pyre. You will just be dead, and still, they’ll be coming for our bodies.’ I am motherfu*king tired of rising from the ashes, and I am a white, cis woman.”

Millicent Souris’ essay on “Drink Before the War” opens with, “I can’t get past the men, can you? Does the word patriarchy roll off the ears without impact any more,” before heading into an exploration of O’Connor’s years essentially imprisoned in the Magdelene Laundries, the state and Church run repositories for “fallen” women. In her memoir, Sinéad details how she’d written the song about how she wasn’t allowed to take her guitar to boarding school, the one thing that helped keep her alive. Souris observes that the song “. . .is a blues song, not because of any chord progression, but because Sinéad sees the world for what it is and laments its hypocrites.”

But there is more power than pity in these essays. Stephanie Elizondo Griest talks about O’Connor’s cover of Bob Marley’s “War,” the song she sung on “Saturday Night Live” and then again at the Bob Dylan Tribute, and tells the story of being compared to “that bald chick . . . who tore up the pope” after giving a public talk where she criticized then-president George W. Bush’s U.S. trade embargo against Cuba. and asks readers, “For what will you be booed, and keep on singing?” Myriam Gurba takes to demand apologies while discussing Sinéad’s cover of Nirvana’s “All Apologies.” And Allyson McCabe, author of “Why Sinéad O’Connor Matters,” describes her reckoning with O’Connor’s life to face the truth about her own.

If this anthology feels like something meant for you, you will read it in chunks, you will go back for re-reads of certain passages, you will read a paragraph and need to put the book down and stare out the window for a few minutes, trying to find some sky or a tree or a bird to clear your mind. You will underline sentences and circle entire paragraphs. You will feel like you have walked into a room where friends and other people who might be very different from you are united in your admiration for an artist who was full of talent, fire, drive and pain. It is specific and personal, but it is also overarching and universal in how it pays tribute to Sinéad O’Connor’s life, work, and ultimate impact.

Read more

from music columnist Caryn Rose