Donald Trump’s deployment of the National Guard, along with other military or paramilitary forces, to “police” the streets of Washington, D.C., Los Angeles and very likely other American cities can be called many things. It’s ominous, and clearly meant to be. It’s dangerous to the future of democracy — assuming, for the moment, that’s still what we have in this country. It’s also clumsy, farcical and potentially self-destructive; I would argue that those qualities complement the menace, rather than undercutting or contradicting it.

But here’s what it’s not: It’s not unprecedented, or even all that unusual. According to the pseudo-moral discourse of “norms” and “guardrails” in which so much of American journalism remains imprisoned, we don’t do troops in the streets in the world’s leading democracy, because then we wouldn’t be the world’s leading democracy, would we? Except, of course, in rare and exceptional circumstances governed by strict rules — which sounds convincing unless you bother to look closely, which is when you discover that the exceptional circumstances have happened pretty often for all kinds of reasons, and the rules are so hazy and indistinct as not to be rules at all.

It’s more accurate to say that there’s a weak political taboo around sending troops into the streets — a taboo almost more honored in the breach than the observance — and that presidents or governors need to embrace or concoct a purportedly compelling reason for violating that taboo. Sometimes that reason strikes most people as plausible, as in the wake of a hurricane, an earthquake or a major wildfire. But not always. Trump is far from the first president to use the National Guard to demonstrate federal supremacy over state and local governments, which is something of a sore point in U.S. history, as you may recall.

Trump is far from the first president to use the National Guard to demonstrate federal supremacy over state and local governments — something of a sore point in U.S. history, as you may recall.

None of which is to say that there aren’t distinctive and troubling qualities to Trump’s ramped-up use of military force in American cities. It’s just that those troubling qualities are inherently subjective. As is so often the case, Trump, molded by the sharper minds in his inner circle, has perceived the flaws and weak spots in our crumbling 18th-century constitutional order and exploited them ruthlessly. What troubles so many non-MAGA citizens (an actual majority, if we believe recent polls) is not the fact that the president is sending in the troops, but exactly who that president is and why he’s doing it.

This is neither an original observation nor an encouraging one, but the second Trump presidency represents the fulfillment, or near-fulfillment, of a tendency toward ever-increasing executive power that extends back at least as far as Franklin D. Roosevelt, and arguably all the way to Abraham Lincoln and the Civil War. This may be too much historical shorthand, but one could argue that the extraordinary extensions of presidential powers that Lincoln used to crush the Confederacy marked the beginning of a process that brought us all the way here, to the brink of a neo-Confederate authoritarian idiocracy. If that’s even 10 percent true, it has to rank as one of the cruelest historical ironies imaginable.

What’s distinctive about Trump’s domestic use of the military, of course, is that the excuse for it is transparently absurd: The alleged disorder the Guard has been dispatched to suppress is either invented or imaginary. In L.A., the crisis was entirely the result of the federal government’s overtly racist and willfully indiscriminate police-state actions, in seeking to detain and deport undocumented immigrants by the thousands (along with whoever else got swept up). There is no crime wave in D.C., as has been extensively documented, but the existence of any crime whatsoever — especially if committed by a Black person — was all that was necessary.

But if we understand Trump’s troop deployments as political theater aimed at his base — and intended both to crush protest movements and divide the political opposition — well, there’s nothing new about that at all. As it happens, I got my first lesson about this as a small child, when then-Gov. Ronald Reagan sent the California National Guard into the streets of Berkeley in May 1969.

OK, that’s not quite true: My memories of those weeks are fragmentary and unreliable, and I lived two miles away from the conflict zone, on a bucolic suburban street of Arts & Crafts houses and enormous plane trees. (A few blocks up the hill from Kamala Harris!) Most of what I actually know about the People’s Park protests I learned after the fact. I told people for years that Berkeley had been under martial law, which wasn’t technically true. To be fair, it kind of felt like it at the time.

(William L. Rukeyser/Getty Images) The California National Guard in Berkeley, California, May 1969.

Even at 56 years distance, these events — which originated in a seemingly minor land-use dispute between community activists and the University of California — seem strangely contemporary. Reagan had been elected on a pre-MAGA wave of right-wing outrage, promising to crush the pre-woke student protests of the late ‘60s, and seized on the People’s Park protests as a golden opportunity for street theater and good TV. He sent in 2,700 National Guard troops, a force many times larger than was conceivably necessary, and they spent the next two weeks breaking up even small and peaceful demonstrations with tear gas, batons, rubber bullets and (occasionally or allegedly) buckshot.

The commander of the California National Guard told the media that “LSD had been injected into fudge, oranges and apple juice” given to troops by “young hippie-type females.”

I must interject here that Maj. Gen. Glenn Ames, commander of the California National Guard, claimed, in a monologue worthy of “Dr. Strangelove” or perhaps “The Odyssey,” that Berkeley degenerates had tried to poison or contaminate his all-American troops: “LSD had been injected into fudge, oranges and apple juice which they received from young hippie-type females.” I think we all needed that.

Growing up in Berkeley involved believing that we were special people in a special place, a notion also enforced (if mostly in a negative sense) by the rest of the world. So the National Guard thing seemed special too. It definitely wasn’t, except for the minor but intriguing point that in Berkeley almost everyone involved was white. Consider these examples, which are by no means encyclopedic.

Draft Riots, New York City, 1863

You can definitely go further back into American history than this, given that the official history of the National Guard is much longer than that of the U.S. military, and begins with the militia established by British authorities in the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1636. But there’s no doubt that the “draft riots” of July 1863, an unstable and ugly combination of class conflict and race war, marked a decisive turning point in the use of federal power to quell urban disorder — and offered a pre-echo of many subsequent events, up to and including Jan. 6.

At the obvious risk of oversimplifying this complicated and dreadful event, what began as a legitimate protest against a harsh conscription law that targeted working-class men — many of them impoverished immigrants from Ireland with no stake in the Civil War — rapidly degraded into an outright pogrom against Black New Yorkers and their homes and businesses, along with government buildings and institutions. Perhaps as many as 1,200 people were killed (no one knows for sure) and thousands more Black residents were burned out of their homes and forced to leave the city.

The mayor and the governor dithered for several days before requesting federal intervention (I don’t know; does anything about that sound familiar?), but finally a force of 4,000 regular Army troops, less than two weeks after fighting at Gettysburg, arrived to stop the violence. Historical scholarship on the draft riots is intensive and disputatious; my only concluding point is that they seem to contain all the most painful and contradictory lessons of our nation’s history in compressed form.

Public school integration, Little Rock, Arkansas, 1957

(Paul Slade/Hulton Archive/Getty Images) National Guardsmen with an African-American student, Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, 1957.

Arguably we should pause to consider the use of federal troops in the South during Reconstruction, which was thematically connected both to the draft riots and to this event. For economy’s sake, let’s skip forward nearly a century to the early years of the civil rights movement and another signal use of federal power. President Dwight Eisenhower — a Republican, in case you hadn’t noticed — sent the National Guard to Arkansas’ capital city to enforce the terms of the Supreme Court’s ruling in Brown v. Board of Education that made racial segregation in public schools illegal.

We need your help to stay independent

Shall we talk about painful historical irony a bit more? This showdown mesmerized the nation and struck many people, in America and around the world, as the beginning of a reckoning with the legacy of slavery that might lead, on some distant day, to a society of genuine racial equality. Well, OK, and it also began the process that turned the white South hardcore Republican — and now we have reached the dystopian-narrative plot point where the possible reversal of the Brown decision no longer seems inconceivable. Nope, I never thought I would find myself writing those words either.

Civic uprising aka “race riots,” Detroit and Newark, 1967

(Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone via Getty Images) The National Guard in Detroit, 1967.

It’s unfair to link the events in these two cities too much. They had disparate and quite different causes, and in the hazy historical imagination they blend together into the “long hot summer” and also into the epoch-shaping following year, when insurrections or riots broke out in numerous cities after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.

But even amid the near-constant social chaos of the late ‘60s, Detroit and Newark stand out for a number of important reasons. In both instances, the inciting incident involved alleged or apparent racist violence perpetrated by white cops in increasingly Black cities. (Neither city became majority Black, however, until after the uprising and/or rioting, when white flight intensified.) The level of outrage and the amount of property destruction was admittedly remarkable, and reflected years of built-up anger.

If anything, the level of state violence in response was even more disproportionate. In Detroit, after Republican Gov. George Romney and President Lyndon Johnson had gotten over their personal and political animosity, they sent in 8,000 National Guard troops and nearly 5,000 regular Army soldiers, all of which arguably made the violence worse. (The Guard shot and killed at least nine unarmed people under, at best, dubious circumstances.)

Rather than offer a potted history of the similar-but-different 1967 violence in Newark, I refer you to Salon contributor Bob Hennelly, who can tell this story better better than almost anyone. Oh, but wait: The truly important part here, I suspect, is that white people, in Michigan and New Jersey and pretty much everywhere else, were terrified out of their wits. The reputations of those two cities were permanently poisoned, and the contagious notion that American cities in general were full of angry Black people eager to commit mayhem spread throughout the Caucasian body politic. As difficult as this may be to imagine, Donald Trump was a 20-year-old college student at the time.

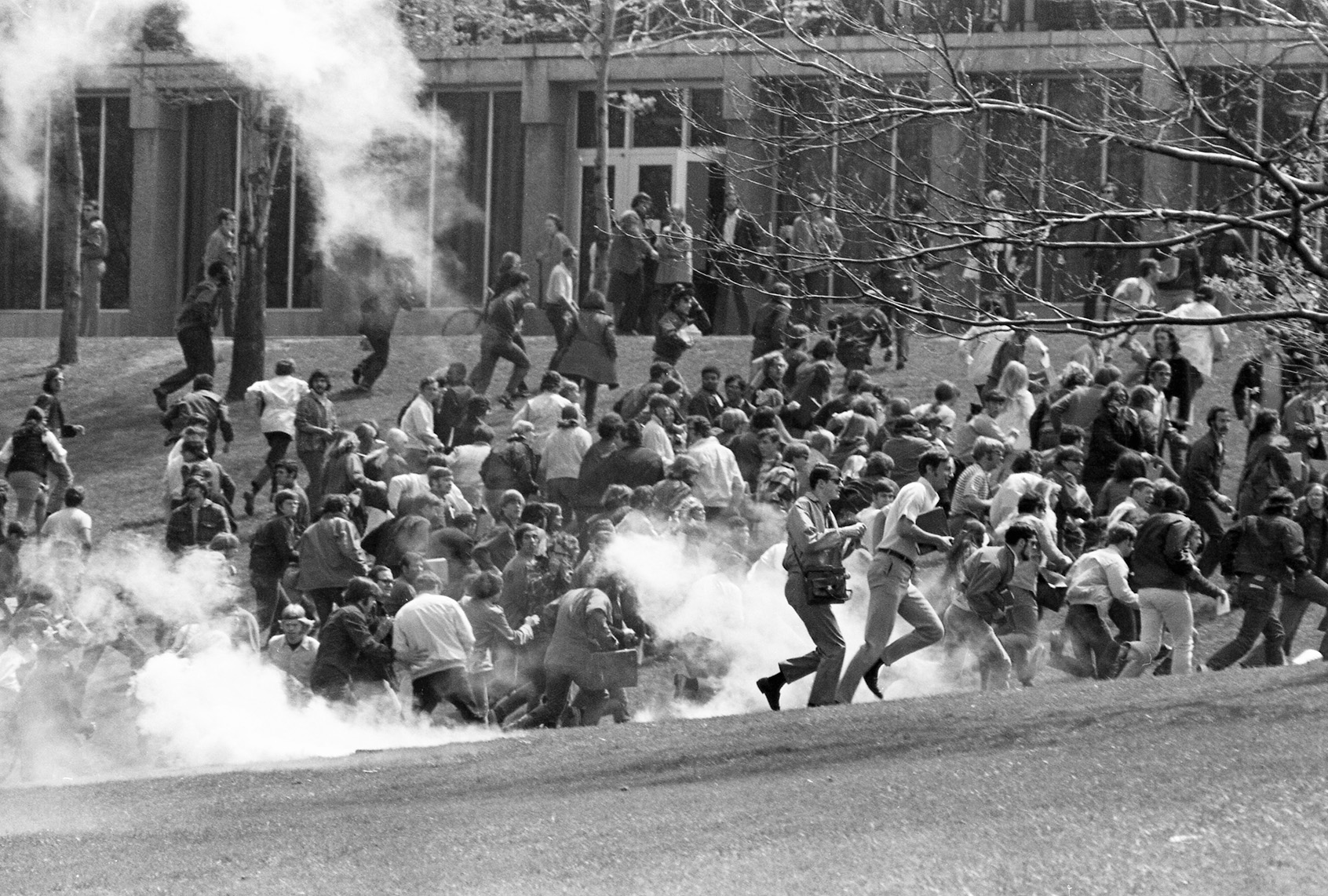

Kent State, Ohio, 1970

(Bettmann Archive/Getty Images) Students flee from tear gas fired by National Guardsmen, Kent State University, 1970.

This perhaps overly-famous event, like the weeks of protest in Berkeley I don’t exactly remember, didn’t have anything to do with race, at least not explicitly. Leading student radical Tom Hayden made a somewhat cogent case, both then and later, that the antiwar movement on American campuses became adjacent to or allied with racial justice movements in the cities, which fueled establishment paranoia and led to exaggerated military response. That sure-enough happened at a normally placid state school in Ohio in May 1970, when a posse of poorly trained and obviously freaked National Guard troops opened fire on a nonviolent demonstration, killing four students and wounding nine others.

Look, I’m not saying Kent State was inconsequential: All lives, in fact, do matter! But in a list full of embedded historical ironies, it’s noteworthy that the deaths of four college kids, as memorialized in a doleful pop-rock ballad, had a generational impact out of scale with a bunch of more dramatic or more violent events. For our current purposes, it’s worth adding that a not-inconsequential percentage of the public looked at what happened in that Kent State field and were like, lol yes!

Rodney King “riots,” Los Angeles, 1992

Here we reach another history-changing event that quite a few of today’s readers can actually remember, which arrived as a massive shock to the American system at the tail end of the supposedly peaceful and prosperous Reagan-Bush I years. After LAPD officers were acquitted on all criminal charges for the vicious beating of Rodney King, an unarmed Black man, much of the metropolitan area erupted in what remains the largest single civil disturbance in American history.

(Steve Grayson/WireImage) A car burns, Florence and Normandie Avenues, Los Angeles, April 29, 1992.

It was another tale of two narratives, set against a social landscape in which violent crime was much more pervasive than it is today. (I know, almost nobody believes this, and you might not either: It’s true!) For many Black people, this was evidence that 25 years after the “long hot summer” very little had changed in terms of police racism and economic segregation. For a lot of white folks, it was more OMG the cities are chaotic, violent and disastrous and we need to lock ‘em all up.

L.A. was permanently changed by the trauma of 1992, and on a national scale we’re still living in its aftermath, which included Bill Clinton and neoliberalism and mass incarceration and other less-than-wonderful outcomes.

There’s no way to sugarcoat the scale of destruction, which extended over more than 30 square miles. Almost no one would claim that sending in the National Guard was unnecessary in this case; it ultimately took 10,000 Guard troops and about 600 U.S. Marines to restore an uneasy peace. Los Angeles and its troubled police department were permanently changed by this trauma, and I would argue that on a national scale we are still living in its aftermath, which included Bill Clinton and neoliberalism and mass incarceration and … wow, somebody stop me before this gets really depressing.

Want more sharp takes on politics? Sign up for our free newsletter, Standing Room Only by Amanda Marcotte, also a weekly show on YouTube or wherever you get your podcasts.

One reason why so many people refuse to believe today’s crime statistics, I suspect, is the enduring suspicion that what happened in ‘92 is waiting to happen again. We could call that bad conscience, but why be judgmental? Oh yeah, and in 1992 Donald Trump was a playboy tycoon in his mid-40s, at the peak of his tabloid celebrity. The King riots, and the Central Park Five case, would shape his understanding of social reality from that moment onward.

Black Lives Matter protests, numerous cities, 2020

Speaking of bad conscience, all of that happened five years ago this summer, after the killing of George Floyd. Seems like yesterday and also like a bygone era, right? The National Guard was called out in lots of places and did very little to reduce the tension, but despite the blatant longings of the guy in the White House, also didn’t make things worse. I think this history is too recent to unpack in any coherent way, but I think the Black Lives Matter summer both led to the election of Joe Biden later that year and to, y’know, what happened after that. Does that make sense?

U.S. Capitol, Jan. 6, 2021

Speaking of not making sense: I don’t really want to dwell on this one, do you? The National Guard got there eventually. Almost everyone who was arrested or convicted got away with it, and a lot of them never got caught in the first place. Do you want me to try to convince you that this event, and its still-unresolved meaning for you and me and our so-called republic, have nothing to do with race? Tell that to Laura Loomer.

Read more

from Andrew O’Hehir on the world and Trump