It may not even be autumn, but already, meteorologists are forecasting slick, icy roads in Park City, Utah, next January. After 47 years attracting both independent filmmakers and ravenous film-lovers to Utah’s rugged hills and snow-capped mountains, the Sundance Film Festival will bow its head before moving to Boulder, Colorado, in 2027 — and there’s sure to be enough tears to fill the streets. What was already due to be a melancholic occasion took on an extra layer of emotional resonance this week, when the festival’s co-founder, actor and director Robert Redford, died at his home in Utah’s Wasatch Mountains.

Beginning as the US/Utah Film Festival in 1978, Sundance eventually transformed into the juggernaut it is today, after Redford’s prestigious Sundance Institute — a non-profit organization shepherding independent filmmakers — took over the festival for its 1985 presentation. Committed to being an incubator for emerging artists outside of the Hollywood studio system, the Sundance Institute’s labs and mentorship programs laid the ideal groundwork for a pipeline between the non-profit and the festival. Over the next 40 years, the Sundance Film Festival would change from a rinky-dink, small-time gathering into a major player in the festival circuit, on par with revered institutions like the Cannes Film Festival and the Venice International Film Festival. It is, undoubtedly, America’s most well-known and well-respected film festival, thanks largely to Redford’s involvement.

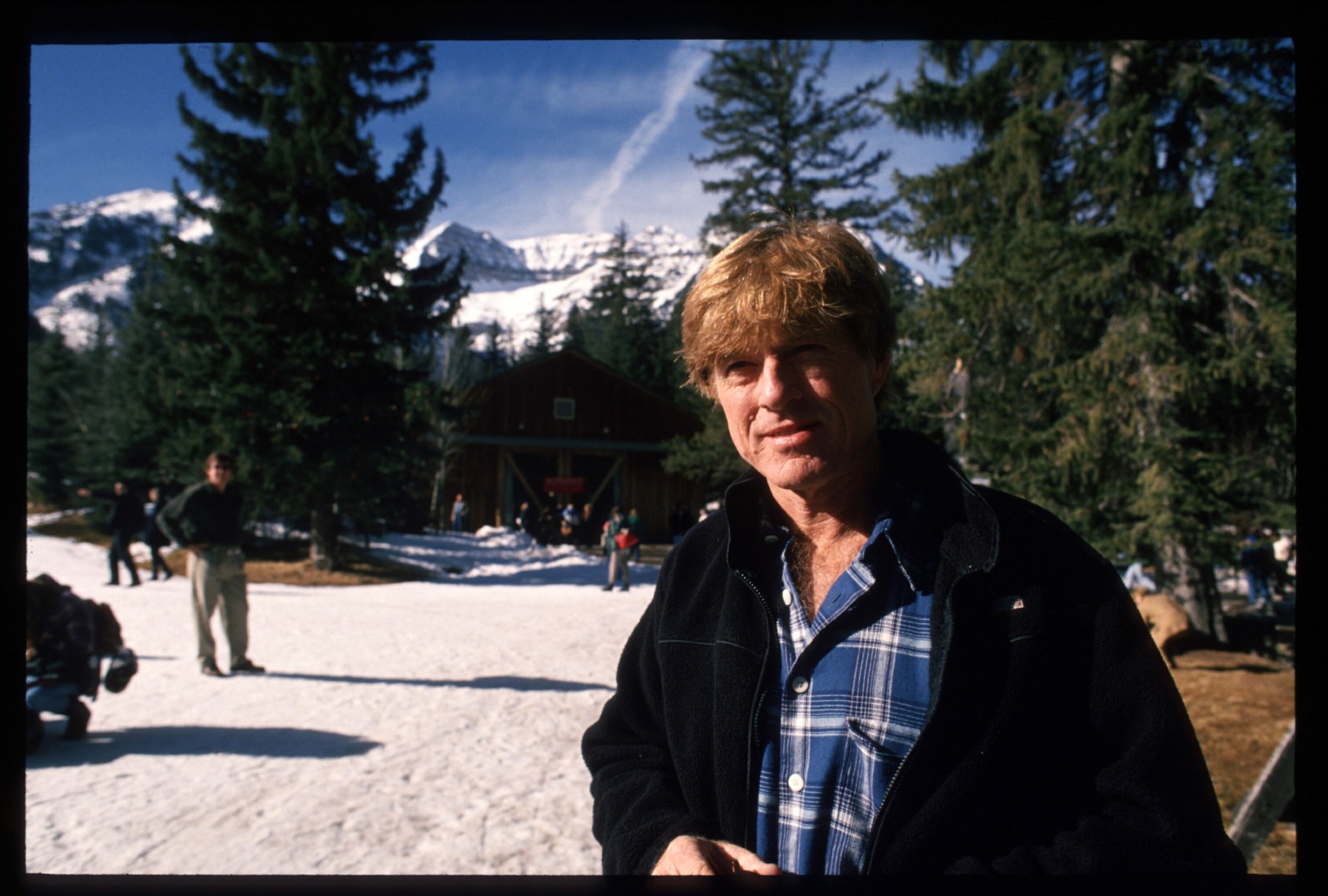

(Randall Michelson/WireImage/Getty Images) Robert Redford during Sundance Film Festival

Redford derided not only crookedness but the perversion of procedure and hard work that resulted in the privileged mounting their success on the backs of others.

Fresh off winning the best director Oscar in 1981 for his directorial debut, “Ordinary People,” Redford could’ve easily spun his prior years of mainstream popularity and current industry success into a lackadaisical lifetime of undemanding roles and fat checks. He had, after all, already become a household name for his work in films like “Barefoot in the Park,” “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid” — for which Redford named his plot of land in Utah, and later, the Sundance Institute — and the ever-relevant “All the President’s Men.” (Remember when film titles could be long and glorious?) Instead, at the height of his renown, Redford turned his eye toward his industry, looking critically at the state of its output. Never much of a Hollywood type himself, Redford’s work in setting up a non-profit that would go on to kickstart the careers of some of independent cinema’s biggest heavy hitters was pivotal for creating a democratized version of an impossible business, one where anyone with a great idea could succeed. Sundance was and is his version of the American dream, built to fit his inclusive, thoughtful dogma. What seemed like a big swing at the time feels even more alien now, in times where good nature is almost a foreign concept. But if the success and impact of Sundance prove anything, it’s that, in a game of underdogs, there is never a bad bet.

Redford, the picture of a classic cowboy and blonde heartthrob, was no stranger to subverting expectations in his work onscreen. For all of his archetypal good looks, Redford had 10 times the depth underneath, bringing volatility and humanity to even his most surface roles. As steely and rough as his gaze could be, there was an omnipresent softness to his work that kept him from being boxed in. In films like the baseball hero story “The Natural,” and in his late-period work in the seafaring epic “All Is Lost,” he exhibited an unduly affection for characters whose lives hadn’t turned out the way they wanted. There was a noted interest in grounded, human stories, targeting bad actors and taking them to task in “All the President’s Men” and Redford’s self-directed film “Quiz Show,” which both revealed corruption being fed to the American people, albeit at different levels. Redford derided not only crookedness, but the perversion of procedure and hard work that resulted in the privileged mounting their success on the backs of others.

It’s no shock that Redford transmitted these morals into his founding of the Sundance Institute, seeing the opportunity to forge a new sector of cinema that reflected a wider idea of humanity that didn’t fit the picture-perfect plastic of the Hollywood box. In his 1999 book, “Cinema of Outsiders,” author Emanuel Levy quotes a 1997 interview with Redford in The New York Times, saying, “The narrowing of the main part of the industry opens up the other part, which is diversity, which is what independent filmmaking is all about.” Redford hoped that the Sundance Film Festival would create a space where indie film could be a “counterreaction against what’s going on [in Hollywood],” citing a lack of diversity within the studio system.

Start your day with essential news from Salon.

Sign up for our free morning newsletter, Crash Course.

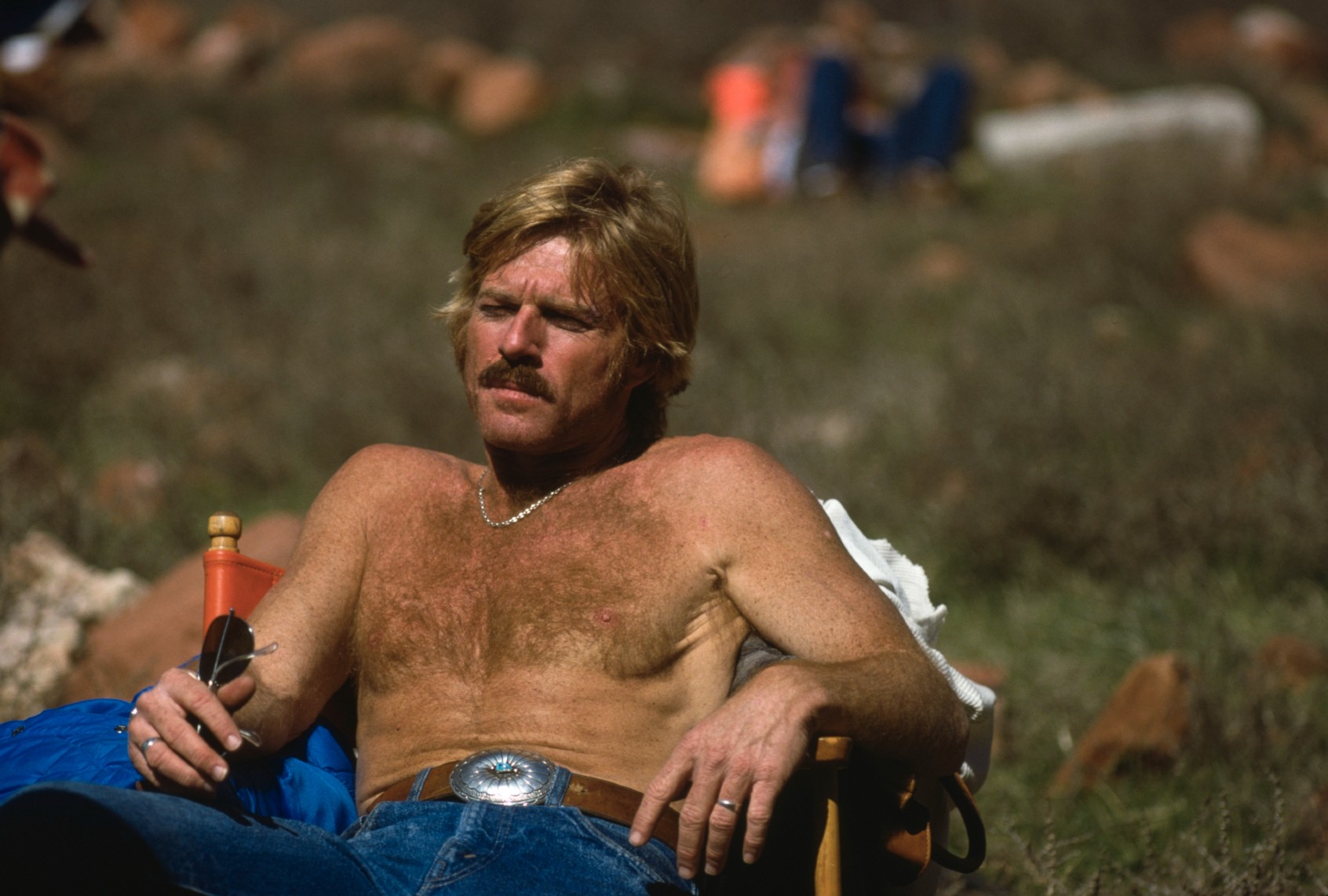

(Ernst Haas/Getty Images) Robert Redford on the set of the film “The Electric Horseman,” in Utah, March 1979.

It worked. Sundance drew such a massive crowd to Park City that the town became America’s premier cultural hub for two weeks every January. The festival is largely credited with the explosion of independent film in the 1990s, with Steven Soderbergh’s “Sex, Lies and Videotape” becoming one of the festival’s first major successes, drawing eyes to Utah and going on to score Soderbergh an Oscar nomination. After that, the floodgates opened, and critics, celebrities, filmmakers, tastemakers, brand sponsors and the general public all flocked to Park City to celebrate the new wave of independent cinema. (And, if you ever feel like spending an hour falling down a fun internet rabbit hole, look up photos from Sundance premieres and parties in the ’90s for some chic, absurd and hilarious photographs of famous people.)

Redford gave writers the chance to write, actors the chance to be seen, filmmakers the chance to create, and viewers the chance to discover films that they truly love, something they might not have ever found if it weren’t for the festival’s commitment to championing independent film.

During that time, filmmakers like Quentin Tarantino and Kevin Smith launched their careers at the festival, and massive, inescapable breakout hits like “Napoleon Dynamite” and “The Blair Witch Project” followed. When Sundance began, Redford was fighting against the mainstream perception that, if a big-name actor did an independent film, their career was in peril. Now, each new Sundance slate brings a spate of major names to the fold, promoting some of their most interesting and eclectic work — some of which may never have been possible for artists to make if it weren’t for Redford’s shepherding. Even so, it’s the smaller titles that don’t always have a name attached to them that are the most indicative of Redford’s mission. The Sundance seal of approval kicks open countless doors to get distribution for independent cinema, A-List celebrities or not.

(GEORGE FREY/AFP via Getty Images) The Sundance Egyptian Theater on Main Street in Park City, Utah, displays messages honoring late actor Robert Redford on September 16, 2025, the day he died at the age of 89.

With press screenings for this year’s New York Film Festival getting underway the day after Redford’s death, it was impossible not to think about how the festival ecosystem has changed since Sundance burst onto the scene. These days, any festival without a decent lineup of smaller, independent films would be rightfully considered archaic. But it’s not only the films themselves that Sundance has helped shape; it’s the people who cover them and see them. Sundance is one of the few festivals with a separate “Press Inclusion Initiative,” a program designed to help emerging BIPOC, women, and queer critics and journalists get unrestricted access to the festival. It’s impossible to say how monumental this kind of opportunity is in a highly competitive industry, one that’s already under threat as it is. I’ve seen firsthand how life-changing being a part of the inclusion initiative has been for my colleagues and friends who’ve had the chance, people I now get to see milling about at NYFF, grateful that they have an open door to do what they love and put something they’re proud of back out into the world. In this short life, that’s all any of us really want: to be happy with how we spend our time, and to make some kind of difference while we’re here.

With the Sundance Institute and the Sundance Film Festival, Redford developed a critical tool for artists to give something to the world, to unleash some seed of an idea that lived inside of them for however long. He gave writers the chance to write, actors the chance to be seen, filmmakers the chance to create, and viewers the chance to discover films that they truly love, something they might not have ever found if it weren’t for the festival’s commitment to championing independent film. Of all of Redford’s achievements, the institute and the festival are the most wide-ranging and everlasting, two shining, defiant examples of how quickly goodness multiplies. Maybe it’s good, then, that the festival is moving closer to the United States’ geographical center. Virtue is a potent thing, and our country could use a little extra goodness radiating from its heart.

Read more

about independent film