In the same week that violent anti-immigrant riots broke out in the western suburbs of Dublin, voters in the Republic of Ireland overwhelmingly elected Catherine Connolly, an independent leftist who has been strongly critical of Israel, the U.S. and the NATO alliance, as their next president. That’s less a contradiction than a reflection of the deep divisions beneath the peaceful, prosperous surface of Irish society.

Those divisions have nothing to do with Connolly’s views on Israel and Palestine, by the way, which are basically the default setting in Irish politics — up to and including the current center-right government (which she opposes). If the U.S. media has largely framed this news as “Ireland elects pro-Palestinian radical,” that says more about our country than about hers. (The hysterical reaction of the right-wing Israeli media, which in recent years has depicted Ireland as something approaching the Fourth Reich with leprechauns, was to be expected.)

But Connolly’s big win definitely represents a dramatic twist in Ireland’s national narrative, just not for those reasons. Since achieving independence just over a century ago — first as a reluctant member of the British Commonwealth and finally, after World War II, as a fully separate republic — the southwestern three-quarters of the island of Ireland have been governed by a rotating cast of vaguely populist and vaguely centrist political leaders. That establishment was shaken but not quite destroyed by two turn-of-the-century events: The collapse of the Roman Catholic Church as a dominant cultural force and the end of the “Troubles,” the decades-long low-intensity civil war in the still-British nation of Northern Ireland.

The two political parties that emerged from the Irish Civil War of 1922 as bitter enemies, today known as Fianna Fáil (“soldiers of destiny”) and Fine Gael (“tribe of the Irish”), have gradually become almost indistinguishable in terms of ideology or policy, even if they still represent somewhat different class and regional interests. For the past decade, in fact, they have governed together in an awkward coalition and, more recently, an orange-slices-for-all arrangement in which the office of prime minister, or taoiseach (“leader”), is passed back and forth between party leaders.

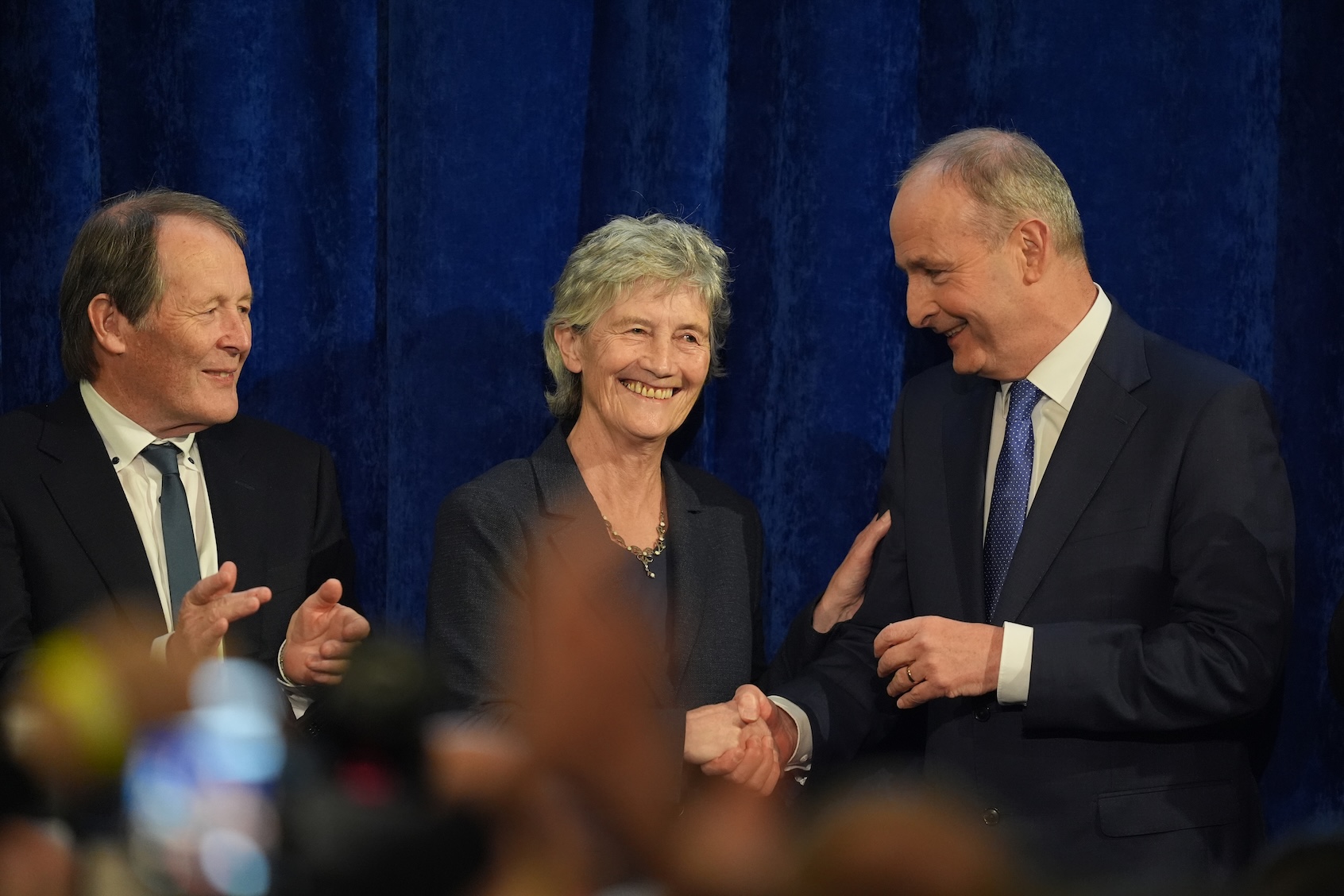

Connolly’s election won’t change that, at least not in the short term. The Irish presidency is a symbolic and ceremonial office with effectively zero executive power; it’s more like being the queen of Denmark than the president of France, let alone the United States. Political power still resides, for the moment, with current Taoiseach Micheál Martin, a canny operator whose principles and policies are notoriously difficult to pin down. (One of my uncles or cousins might describe him as a “cute hoor,” and not entirely mean that as an insult.)

We need your help to stay independent

Still, Connolly rolled up 63% of the vote, more than double the total of unobjectionable mainstream candidate Heather Humphreys, who seemed like a nice person perennially on her way to or from the ladies’ lunch at the country club. (Yes, religious bigotry is supposedly a thing of the past in Ireland, but the fact that Humphreys is a Protestant didn’t help her candidacy.) Humphreys’ landslide defeat was a major embarrassment for the FF/FG government, whose leaders spent the final days before the vote pleading with voters of “middle Ireland” to prove that “this country is not far left.”

Connolly is a forceful representative of the left-leaning Irish nationalist tradition, but viewed through the prism of Western democracy in crisis, her big win also has an unmistakable Bernie-Zohran flavor.

Well, sure; Ireland isn’t far left or far anything else. In relative terms, it remains a highly cohesive society. There’s an angry but marginal anti-immigrant minority, and while overt racism and bigotry certainly exist, they face widespread mainstream disapproval. To this point, Ireland is pretty much the only nation in Western Europe without a significant far-right political party, a fact that reflects the strong historical connection between Irish nationalism and anti-imperialist or anti-colonial ideology. A handful of far-right and/or celebrity candidates tried to get on the presidential ballot and failed, including mixed martial arts fighter turned MAGA hanger-on Conor McGregor and Riverdance impresario Michael Flatley. The saga of ultra-Catholic right-wing lawyer Maria Steen and her €10,000 Hermès handbag is definitely worth recounting, but perhaps over a pint rather than here and now.

Catherine Connolly is a forceful representative of that left-leaning Irish nationalist tradition. But viewed through the prism of Western democracy in crisis, her big win also has an unmistakable Bernie-Zohran flavor. Younger people who feel disenfranchised and ignored by the mainstream consensus politics that have fueled growing economic inequality and an intractable housing crisis — rents and home prices in Dublin are worse than London, and comparable to New York or San Francisco — turned out for her in the hundreds of thousands. Five left-of-center opposition parties with a long history of mutual mistrust, the largest of those being Sinn Féin (formerly associated with the IRA’s guerrilla campaign), put their differences aside for the moment to back a candidate who didn’t officially belong to any of them.

Want more sharp takes on politics? Sign up for our free newsletter, Standing Room Only by Amanda Marcotte, also a weekly show on YouTube or wherever you get your podcasts.

Connolly is a fluent speaker and booster of the Irish language, which became a surprisingly important signifier in the race, as Humphreys “has no Irish,” to use the vernacular. On the global stage, Connolly supports the longstanding principle of Irish neutrality: Ireland is a charter member of the EU but has never joined NATO, and by law its (tiny) military force may only be deployed on UN peacekeeping missions.

To be clear, as president she’ll have no meaningful influence over foreign policy or affordable housing or much of anything else. She can appoint commissions with no actual powers, welcome foreign dignitaries — no doubt gritting her teeth in some cases — and use her language skills to congratulate the winning team in Craobh Shinsir Peile na hÉireann (i.e., the All-Ireland Gaelic football championship). There’s a truism that the Irish vote their values in presidential elections and their pocketbooks when electing the actual government, which may well hold true. But values matter too, especially over time. It won’t change the course of history that a huge majority of voters on a small island at the western edge of Europe rejected both the stagnation of mainstream politics and the noxious rising tide of the far right. But it might just be a sign.

Read more

from Andrew O’Hehir on the Emerald Isle